|

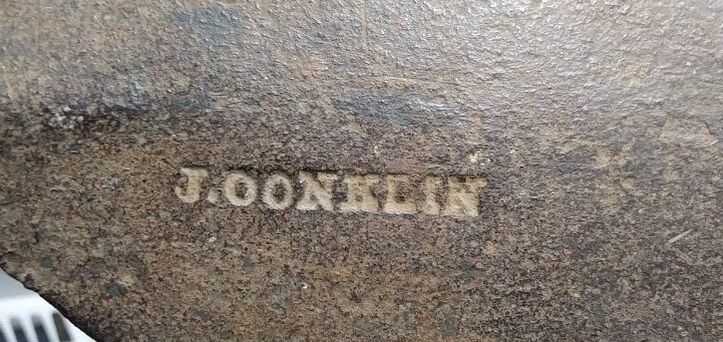

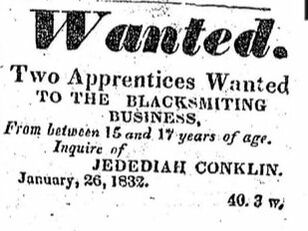

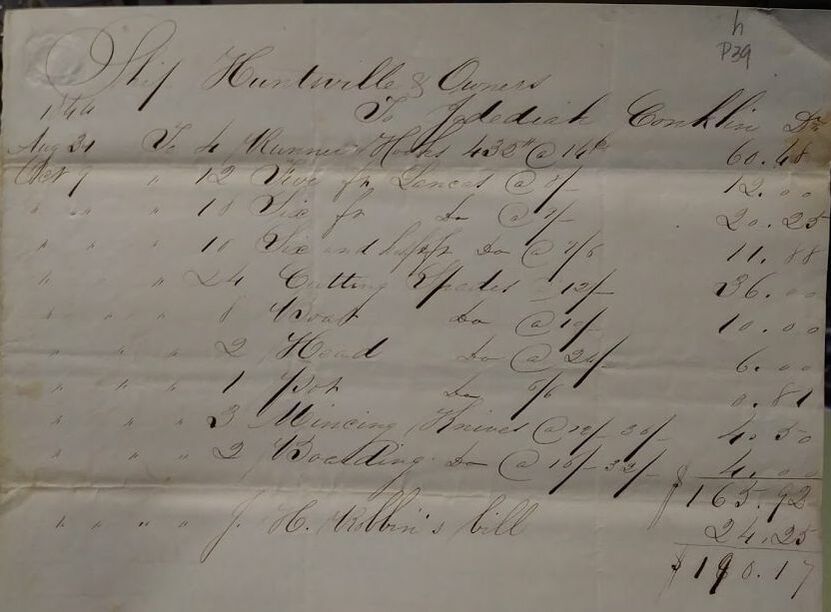

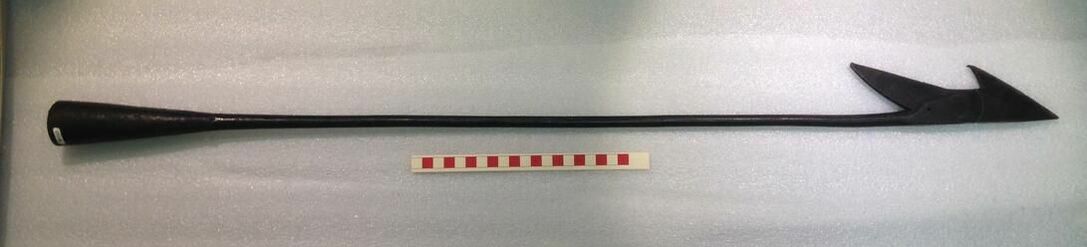

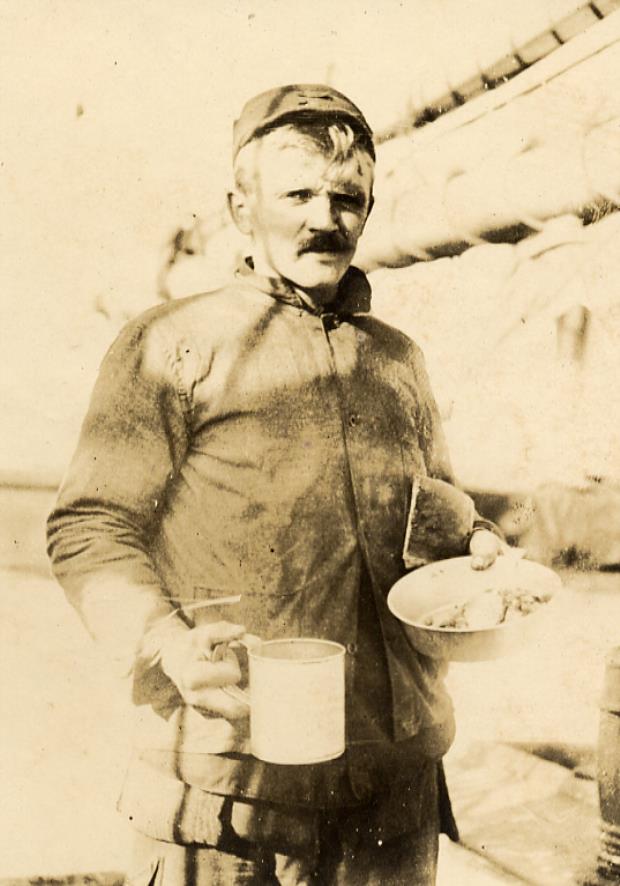

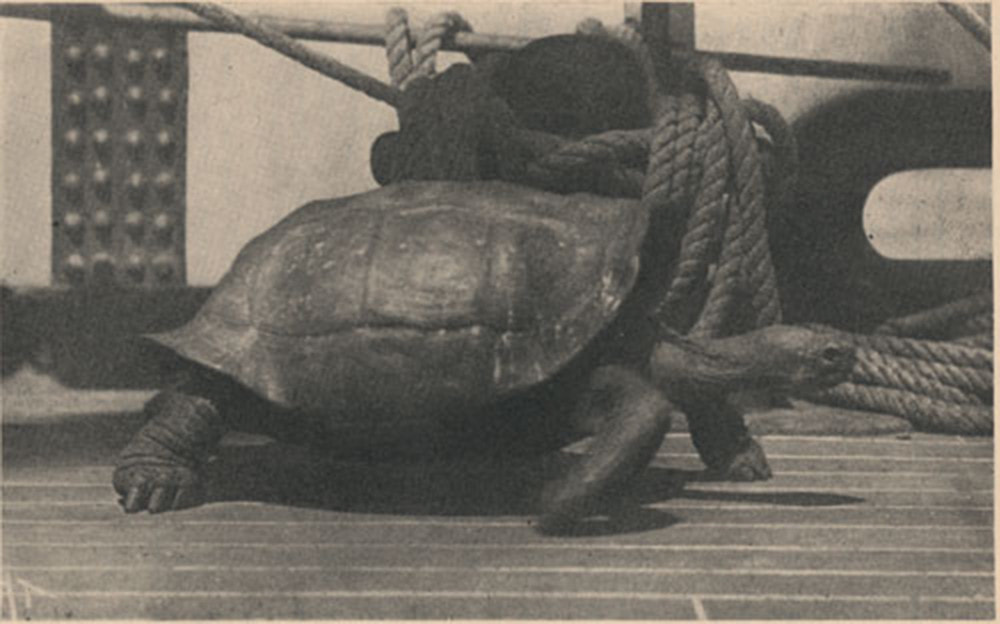

Whaling Museum Acquires 4 Artifacts of Jedediah Conklin: Master Blacksmith, Gold Digger, and Oldest Resident of Sag Harbor by Nomi Dayan, Executive Director The Whaling Museum recently acquired 4 objects into its collection, one harpoon and three boat spades, dated from the 1820’s-50’s. All objects had a maker’s mark: “J. Conklin.” Who was he? Jedediah Conklin was born in Amagansett on February 17, 1798 to Henry Conklin and Esther Baker. His Conklin side (sometimes spelled Conkling) could be traced back to one of the four original families who broke away from comfortable East Hampton to bravely start new families in what was then the wilderness. Given the same name as his uncle, Jedediah was baptized that June. His parents let no disciplinary opportunities slide, as he later recounted: “My people never spare the rod and spoil the child; my father whipped me today for throwing stones at my grandfather.” Henry likely chose Jedediah’s trade for him, and he chose well: blacksmithing, a highly skilled occupation held in the highest esteem. In an era when each nail and each link in a chain was handmade, this trade was in high demand in many communities at the time – and perhaps Sag Harbor most of all as the village boomed into the 5th largest whaling port in the country. Young Jeremiah learned to work with extreme heat for twelve-hour shifts, pounding a heavy sledge over glowing-red metal, sparks bouncing off his thick leather apron. Over the heat of fire, he used his strength and knowledge to perfect the transformation of iron into whatever tool his customers demanded. Those items were whaling gear: arrow-straight harpoons, razor-sharp lances, flat cutting spades, and barrel hoops, all designed to bring back the richest oil the world had ever known. Into each of his creations, he stamped his maker’s mark: J. CONKLIN. Jedediah’s career bloomed marvelously with the golden age of whaling. Sag Harbor was thriving, and he was the mechanical backbone of it. With a good job and steady income, he married Frances Puah Terry (b. 1807) of Aquebogue in his mid-twenties. For the first time, he appears as Head of Household on the 1830 census. The earnings of a blacksmith were lucrative, but chasing people to settle their bills was another matter. In 1831, he placed an ad in the paper informing “all those who are indebted to him, or whose accounts with him are unsettled” that unpaid debts will be placed in the hands of an attorney for settlement. No doubt he needed the money: his family would quickly grow to have six children: John Barker, Dorliska, Catherine, Henry, Evelyn, and Mary. In 1832, he took the career-affirming step by advertising his desire to take on two young apprentices, who would agree to work for a number of years to learn the “art and mystery” of the trade. One of his apprentices was John Fordham, who was only 12 when he became Jedediah’s apprentice, sleeping in the attic with mice running over his legs. In his late teens, John progressed to earn a dollar a day, and continued to work for Jedediah after he married (and later even purchased his shop). His apprenticeship served him well, because John became an expert smithy who at one point employed 12 men in his shop. Business continued to grow. Jedediah could hardly get harpoons out fast enough as demand for blacksmiths soared. After moving several times, in 1833 he purchased a lot near the water in Sag Harbor measuring 60 feet by 100 feet for $135. Soon, whaling companies not only in Sag Harbor were relying on him, but the relatively new Cold Spring Whaling Company paid him for lances, an assortment of spades, hooks, and knives for the Tuscarora’s 1843 voyage and again in in 1844 for the Alice and newly purchased Hunstville. He wasn’t the only blacksmith on the block: that same year, new neighbor John Cook, a fellow blacksmith, planted himself right next to Jedediah and advertised his harpoons and whale craft sold from his blacksmithing shop “opposite the shop of Jedediah Conklin.” Although there was more than enough work to go around, the close competition didn’t matter, because Sag Harbor suffered an epic and disastrous fire the next year on a windy November morning in 1845, wiping out provisions just before winter. Both blacksmith shops were reduced to ashes among 95 other buildings. 40 families were homeless. Sag Harbor was not the same after the fire. Although the whaling industry peaked over the next few years, the trade declined into a collapse shortly after. Jedediah himself was also perhaps not the same: his eldest son John died at the age of 21 in September 1848. He likely tried to throw himself into his work, but less people were waiting in line for his harpoons. When gold fever swept through Long Island, Jedediah was no exception among the Sag Harbor men whose imaginations were hit hard. He joined a group of men from Sag Harbor and the Hamptons who formed the Southampton and California Mining and Trading Company and became one of 60 excited stockholders. If Jedediah hadn’t learned to swear well by then, he certainly picked it up from the 16 whaling captains aboard. After supper one day, he was standing mid-deck chatting with several others when the person at the ship’s wheel played a trick and angled the ship to meet a good-sized wave, which doused Jedediah. The reteller of the story said, “I cannot repeat his language, but you may suppose - it was no song of praise.” Two weeks out, the Sabina began to leak in the middle of the Atlantic, but the seasoned crew kept going. The Sabina finally arrived in San Francisco in August 1849. As described by a fellow crewmember, Jedediah saw busy harbor which “resembled New York on the Pacific… The buildings are of the frailest and cheapest kind. A great many businesses operate under large tents… We shall probably start as soon as Monday for the diggins.” The crew raced into the wilderness, sleeping in an enclosure made with a tier of logs and blanket for a roof. No doubt Jedediah’s muscular pounding arm came in useful for digging. Life quickly turned difficult. Not only was there no gold, but men starting getting sick, and Jedediah stayed with the ill in Sacramento as other hired wagons and mules to search further. Just one month after arriving, the team decayed; it was now every man for himself. After half a year, Jedediah gave up for good and departed home January 23, 1850, his golden dream gone, the Sabina sadly abandoned in port to rot. Life moved on – and in exciting ways. While Jedediah was in California, the whaling world had been taken by storm when Lewis Temple, a freed slave and New Bedford blacksmith, improved the toggle harpoon in 1848, dramatically increasing whalers’ success at sea. This tool quickly became the standard in the industry. Jedediah must have studied this curious hinged barb with excitement; he fired up his forge again and tried his own hand copying this design, which he was free to do, as no patent had been filed. When the harpoon was complete, he didn’t know where to press his maker’s stamp. As if out of respect for the new design, he chose an unusual spot – low down on the harpoon’s shank. He then slathered the iron in red primer, followed by a thick black coat of paint, and placed his proud harpoon for sale. The object never found a buyer. It quietly sat on a shelf collecting dust as buyers reached past it for other things. No matter - Jedediah had other inventions up his sleeve. In 1854, he announced “Lightning Rods!” were for sale, acting as agent for the east end. He promised a conductor “uniformly pronounced by scientific men to be the safest and best means of protection against lightning ever offered to the public.” Jedediah continued his progressive stance by sending at least one of his daughters to school. Flushing Female College, an institution “for the solid and ornamental education of Young Ladies,” listed Jedediah as a reference in 1855, along with fellow Sag Harbor whaling Captain Wickham Havens, who also sent his daughter there. For the first time, Jedediah’s family started thinning: Dorliska married in 1857, and Catherine followed in 1859; his second son, Henry, died in his early twenties in 1864. Jedediah decided to downsize, sell his house, and rent elsewhere. In 1866, he advertised the sale of a “two story dwelling house, situated on Division Street, and nearly opposite the rear of the store of William H. Tooker,” a merchant of a country store. Even as Jedediah aged, he continued adapting to a world where he was not needed to build tools anymore; factories were taking care of that. He turned his attention to the next big thing – machine and equipment repair. He announced in the newspaper in 1860 that in addition to his former business, he was partnering with his old apprentice John Fordham “to do all kinds of Machine work, especially repairing Horse Powers, Mowing Machines, Thrashing Machines, all of which will be done in the best possible manner, and warranted to give satisfaction.” His shop continued to rent space to other blacksmiths. One advertised in 1869 that he was working in Jedediah’s shop repairing stoves, flat irons, locks and keys, tools, and farming work, machines and wagons. In 1871, Jedediah advertised that he was selling axes, stalk-hoes, and wagon tires. He also advertised selling 2,000-3,000 second hand bricks, which possibly came from the rear and east wall of his shop which caved after a bad storm, which he promised to sell at a good price. Jedediah likely noted the good price because Sag Harbor was in a depression. In the 1870’s, the neighborhood was described as “one deserted village – a seaport from which all life has departed.” Nevertheless, Jedediah hung on and continued to branch out by becoming an owner of the Mansion House, a four-story stately 1846 building built with Philadelphia pressed bricks. In the Long Island and Where To Go publication by the LI Railroad Company in 1877, “Mrs. Jedediah Conklin” was listed as a good place to stay. In the 1880’s, he became a trustee of the Sag Harbor Savings Bank, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. Jedediah watched the world continue to change around him as new technology and mass production edged out the once-secure blacksmithing craft. Although he had weak eyes later in life, Jedediah seemed to outlast everyone around him, with newspapers calling him a “conspicuous example of Long Island longevity.” Half of his children (that we know of) died in his lifetime. His wife died suddenly in 1885 after falling in a fit while cleaning the house. But Jedediah kept going: in 1890, he found himself the oldest person in the township. Oldest or not, he continued to stay active, and not even ice would hold him back. The Newton Register noted on a frigid March day in 1890: “From Sag Harbor: Notwithstanding the mercury ranged down about ten degrees on Friday, and our streets were glazed with a coating of slippery ice, one of our vigorous old citizens was seen making two or three trips up and down one of our thoroughfares. Mr. Jedediah Conkling is 93 years old, and yet hale and hearty and active as many men at twenty his junior.” He must have loved walking, because that year the newspaper reported he walked 5 miles to Hardscrabble. His active lifestyle came to an end one Saturday morning when he got up from his chair and fell, stricken with paralysis. Bruised and unconscious, he died the following Wednesday on April 8, 1891 at 93 years old, 1 month, and 22 days. The bank noted he was “known and honored by us all for his personal kindness, for his unfailing zeal,” and “he was the gift of the eighteenth century to the nineteenth.” He was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor. His surviving grandchildren blew around the country, including Oregon and Minneapolis. After Jedediah’s passing, his creations remained behind – those rods of iron he painstakingly and masterfully fashioned for whaling voyages were now on collectors’ shelves. One collector was Bob Hellman of Nantucket, a scholarly enthusiast of whaling gear. After he passed away in 2018, his wife Nina Hellman, owner of a marine antiques shop who had appraised the museum’s collection years back, privately sold the items at a reduced price to the museum. While the portraits of whaling captains often get the glory of our country’s long history of whaling, those silent maker’s stamps frozen into iron are lasting testaments to blacksmiths’ essential contributions to the industry. Before whalers’ eyes could scan the seas for whale spouts, they first visited East Water and Main Street in Sag Harbor and waited, just as Melville described the blacksmith in Moby Dick: "Often he would be surrounded by an eager circle, all waiting to be served; holding boat-spades, pike- heads, harpoons, and lances, and jealously watching his every sooty movement, as he toiled." Thank you to Rebecca Grabie of the John Jermain Memorial Library for research assistance. References Armbruster, Eugene L. Amagansett / Wainscott, Long Island: Jedidiah Conklin House, north side of Main Street.. 1923. New York Historical Society, New York. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph collection, 1894-1939. Series II: New York City Negatives Brewster-Walker, Sandi. The gold rush of 1849: we got a little gold! Part 2. Amityville Record. February 17, 201. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb 25 1889 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 17 1889 Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Many Long Island Men Among Gold Seekers in 1849. October 26, 1849 The East Hampton Star. (East Hampton, N.Y.), August 09, 1929, Page 6, Image 6 The East Hampton Star. (East Hampton, N.Y.), July 25, 1940, Page 2, Image 2 Conklin, Joseph Inglish Jr. Copy of Conklin genealogy 1875-1908. Presented to the Huntington Historical Society through Tarrytown Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution, Copied from the original February 1947 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), June 11, 1831, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), February 09, 1833, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector., (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), October 27, 1838, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), April 20, 1844, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), July 29, 1854, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), September 01, 1855, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 16, 1891, Page 2, Image 2 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 2, 1885 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 23, 1885, Page 2, Image 2 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), February 26, 1910, Page 5, Image 5 The County Review., (Riverhead, N.Y.) August 15, 1924, Page 9, Image 9 Field, Louise M., ed. Amagansett: Lore and Legend. 1948. Amagansett Village Improvement Society. Amagansett, NY. Islip Bulletin., (Brentwood, N.Y.) May 16, 1974, Page 12, Image 12 Mallmann, Jacob E. Historical Papers on Shelter Island and Its Presbyterian Church. 1899. Shelter Island, NY. Newton Register, March 13, 1890 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), June 27, 1867, Page 3, Image 3 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.) Feb 17, 1870 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), August 31, 1871, Page 3, Image 3 Sag Harbor Express., (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), April 03, 1952, Page 2, Image 2 Sag Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), August 31, 1972, Page 1, Image 1 Sag Harbor Express. (Sag Harbor, N.Y.) May 14, 2015, Page 9, Image 9 The Traveler. April 17, 1891. Southhold, NY. Obituary Wiley, Nancy B. John Fordham, Harpoon Maker. Aug 1851. Long Island Forum. Additional: Whaling Museum Archives

4 Comments

Norwegian-American whaling captain C. T. Petersen climbing the rigging, circa 1935. Courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum Norwegian-American whaling captain C. T. Petersen climbing the rigging, circa 1935. Courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum By Joan Lowenthal Recently a visitor to the Museum was reading an excerpt from the displayed logbook of the whaleship the Sheffield. He read that on Thursday, May 21st, 1846 while taking in sail at sunset, Scudder Abbott, a crew member on the Sheffield, lost hold and fell about 70 feet from the topsail yard to the deck. He became delirious and blood ran from his mouth and nose. He was immediately taken to the cabin and bled and made as comfortable as possible. The next day he was at times sensible and then again quite deranged. The visitor wanted to know if Abbott survived the fall. Did he? Whaleships and the nature of the whaling industry were dangerous, and the Sheffield was no exception. She was the largest whaler sailing out of Long Island, and the third largest whaler in the US. She was purchased in 1845 by the Cold Spring Whaling Company and boasted an impressive history of speedy, having broken records by crossing the Atlantic in only 16 days. Onboard whalers, there were commonly shipboard accidents, fighting, illnesses, food poisoning, drowning, and of course the dangers of hunting a powerful whale. Captains were responsible for dealing with illnesses and injuries aboard. They used their limited medical knowledge and supplies from the onboard medicine chest. Starting in 1790, the medical chest was part of legal required equipment on all American ships of 150 tons or more with ten or more people on board. The chest contained vials of drugs from powdered rhubarb to arsenic, identified by numbers which corresponded to recommendations outlined in a list of symptoms. During a time when doctors may not have been much more knowledgeable than the captains themselves, many times the treatments were worse than the injury or illness! After Scudder Abbott fell, as the logbook records, he "was taken up senseless in the cabin and bled and everything that we know of to make him comfortable." Considered one of medicine’s oldest practices, bloodletting was the standard treatment for various diseases. The logbook continues to document his recovery. The following day, he was "at times sensible and then again quite deranged." On Saturday, May 23, 1846, Abbott was "still out of his head but he was able to sip some soup and drink some sage tea." Sage tea has been used medicinally throughout history to help improve a variety of health issues. Two days later, the logbook records light squalls of wind and rain, and states Abbott seemed more rational and appeared to be “in the gaining hand.” Thursday, May 28th, after noting fog and unpleasant weather, the logbook records: “The invalid Abbott is much the same as yesterday, rather stronger but rather out of his head.” Abbott is briefly mentioned thereafter. On Sunday, June 14th, 1846, the logbook states, "Right Whales were chased sometime without success. Abbott was well enough to stay on deck all day for the first time since he fell from aloft." But the very next day, he remained forward in his bunk. The last entry about Abbott was on Friday, October 8th, 1846. The logbook simply stated that "S. Abbott rather better." Nothing is known about Abbott past this point, even after searching crew lists. With his lucky survival, he quietly vanished back into the workforce of thousands of crew members who faced incredible and serious risks in order to light the world. For more information on medical practices on board a whaleship check out Hen Frigates Passion and Peril, Nineteenth-Century Women at Sea by Joan Druett (A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster, 1998). By Nomi Dayan As we celebrate all things spooky, gory, and creepy this season, consider a few extra-repulsive experiences of 19th century whalers to give your Halloween festivities an extra kick. 1. Wash Your Clothes -- with Urine There was no Tide at sea, and no Febreeze in those sea breezes. Not only were there no cleaning products for a whaling crew, there was was no toilet, either. These two problems came together into a (literal) solution: seamen regularly used a communal urine barrel for the purpose of using urine as a cleanser. The deck was scrubbed with urine, and grease-sodden whaling clothes were soaked in it. As disgusting as the process sounds – or smells - urine contains ammonia and has a long history as a cleansing agent. Even ancient Roman laundromats used publically-collected urine to clean clothes, and the laundry worker would use his or her feet as an agitator. 2. Eat Whale Brains

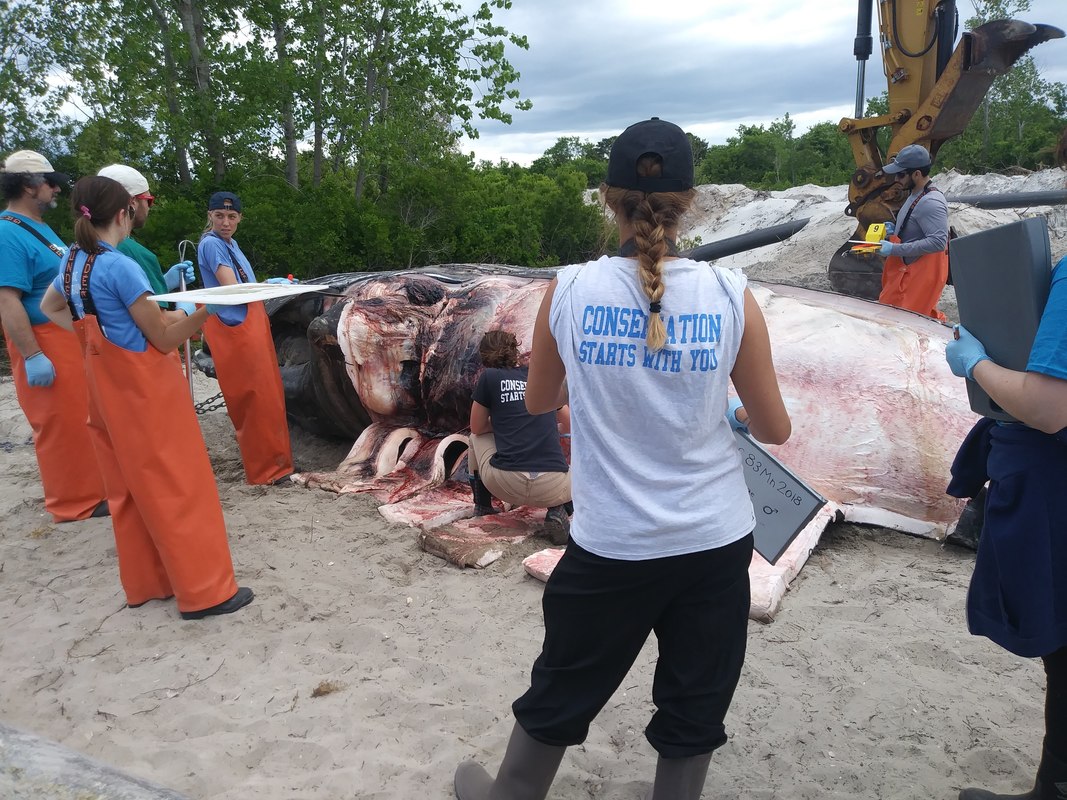

“That mortal man should feed upon the creature that feeds his lamp and eat him by his own light – this seems so outlandish a thing,” Melville muses in the Moby Dick chapter, “The Whale as a Dish.” In contrast to the Inuit and Japanese who have long histories of eating whale meat, most Americans never developed a cultural taste for whale. Nevertheless, every whaler would have encountered assorted body parts of whales on his plate at some point. The seafarer’s menu included fried, flour-coated pilot whale brains, sperm whale tongues, porpoise meatballs, right whale steaks, and doughnuts fried in whale oil, the latter of which was a crew reward for reaching 1,000 barrels of oil. Although these meals provided a break from worm-infested food on board, whalers generally did not regard whale meat as part of a ‘civilized’ diet, and the stigma-laden consumption was linked to poverty or barbarism. 3. Live With Roaches Climbing Up Your Legs There were bugs of all kinds on whaleships, from weevils in flour to bedbugs in bed. While on the Tiger, John Perkins noted that when a cask of bread was opened, it was wormy, but “the worms taste no different from the bread.” But the indisputable king of insects on a whaleship was the cockroach. You could even hear them skittering among the ship planks, as one whaler described the rustling sound in 1841 as “a flush of quails among the dry leaves of the forest.” When William Davis woke in the middle of the night on a whaleship, he felt “the wretched sensation of an army of cockroaches climbing up [my] legs,” and when he checked a small amount of food he had stashed away from dinner, he found his tin plate “scraped clean by the same guerrillas. They leave no food alone.” Yet, it seems that with time, even the most picky individuals came round to accepting their insect roommates. J. Ross Browne wrote in 1846 that while a fly on his food would have bothered him before his whaling voyage, “it did not at all affect my appetite to see the mangled bodies of diverse well-fed cockroaches in my molasses; indeed, I sometimes thought they gave it a rich flavor.” Nomi Dayan is the Executive Director at The Whaling Museum & Education Center. By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director at The Whaling Museum Photos taken under Research Permit AMCS #2094 When a whale beaches itself in the Long Island area, dead or alive, one man’s cell phone rings first. That man is Robert DiGiovanni. He’s the founder of the relatively new Atlantic Marine Conservation Society and its stranding response team, whose Facebook page becomes pocked with crying emojis when a dead or dying whale collapses onto the sand. I first met Rob at a beer and cheese tasting at The Whaling Museum, where he gestured to the whale models as he talked. While we chatted, he mentioned he was going to be performing a necropsy on a young Humpback whale spotted swimming the day before in Reynolds Channel in Far Rockaway. Now it was floating dead on a sandbar near Atlantic Beach Bridge - the 4th dead humpback on Long Island in less than a month. A necropsy would help explain why. My eyes lit up. A dead whale! I half-heartedly asked if he ever allowed guests to view the process. As if on cue, Ken Pritchard stepped up, sensing an opportunity. He is the museum Vice President and Commissioner of Sanitation for the Town of Hempstead, and helps oversee how the whale’s final resting place will be prepared. Ken whipped out his phone and held Google Maps open for Rob to point at. With his big fingers, Rob poked a spot off of Loop Parkway. Tomorrow morning, ten o-clock. I could barely sleep the night before. I had been teaching about whales for years, but I had never actually met one. I was like an informative field guide for a country I had not visited. Sure, I had caught breathtaking but elusive glimpses of blowholes and flukes from nauseating whale-watching trips, but everything else I knew about whales was devotedly learned from documentaries and books. I had handled whale teeth, but only after being passed through a whaler’s hands two centuries earlier. I had led kids through blubber insulation experiments, but never actually touched the real thing. What would it smell like? Feel like? Are dissections somber? What about the notorious stench I had heard about? “Boots better than shoes,” Ken texts that morning. I stare into my closet. What do you wear to a whale dissection? I decide on denim with my trusty museum uniform shirt which has the necessary whale-tail on it to help me feel official in a place where both the whale and I will be out of its element. After a short drive to Alder Island near Point Lookout, where street lights wear the spiky hats of osprey nests, Ken pulls over to a small clump of cars on a spot by the side of the highway. He wonders out loud if the car will combust from igniting the long grasses. We step out of the car, spark-free. Ironically, the area has a strong whaling history. Major Thomas Jones established a whaling station near present-day Jones beach in the early 1700’s, creating a successful monopoly around “Mereck Beach.” We search for the same goal today, a dead whale, as we venture past ubiquitous poison ivy to a random path of surprisingly soft and white sand. A Gator utility vehicle miraculously appears behind us and offers us a ride; Ken gallantly rides in the back. After a few moments of wobbling, we round a ridge of sand, and suddenly -- there it is. Before us lays a large, dead whale on its back. Its huge throat grooves are thrust up to the sky, inflated with bloat, like a giant tire half. Normally neatly pleated and only expanded to gulp water while feeding like the other great rorqual whales, the grooves are now stretched like a drum and engorged with air, deeply stippled with light and dark lines, like elevator treads. The middle of its body is centered with a small notched dimple, none other than its belly button. The whale’s notched pectoral flippers are splayed and are surprisingly long - a characteristic of humpbacks. Its genus, after all, is megaptera, meaning large wing. A humpback’s flippers are third of its body length, used to propel the whale through its herculean annual migrations, one of the longest of any mammal, not to mention spectacular aerial displays emblemized both by environmental organizations and Pacific Life Insurance. There are about ten quiet people there, most of whom are volunteers. They are wearing blue gloves and waterproof bib overalls so bright an orange that Home Depot would be proud. The backs of their t-shirts boldly state Conservation Starts With You. Supplies and a table are set up under a blue pop-up tent. Rob is there, directing volunteers how to cut into the side of the whale with machete-like flensing knives. People look dwarfed next to the whale, like fire ants cutting into the side of a large fish. I whisper to Ken, “Can I touch the whale?” “Just do it,” he hisses back. “That’ll make two of us at the museum!” The wind shifts, and suddenly we inhale the wall of stench that slams into us. We let out a choked ugh. The air reeks of rotting fish, rancid meat, and vomit. Bubbling gas is fizzing out of deliberate cuts along the whale’s side. We got it right, I think, remembering the customized scent stations we designed in the museum where visitors can smell a whaleship. I suppress a gag reflex and side up to one person. She is part of a volunteer team from Mystic Aquarium. It is a skinny male, she says, now known as AMCS83Mn2018, and is about 3-5 years old. The image of a mother and baby whale is one of the most endearing icons in nature. This whale, now a teenager, nursed from its mother for about a year, gaining several pounds a hour on toothpaste-thick milk which was 50% fat, far more than the scanty 4-5% fat in human milk. His mother would have taught him all she knew - how to communicate, how to behave, how to evade predators, preparing him for a life that should have gone to 50 years, and possibly to 100 (a century away from the 200-year longevity reported in Bowhead whales). Large, black flies are everywhere, unable to believe their compound eyes. I brush aggressive ones from my face. For them, this whale is the singles bar of the century. They are checking each other out on the whale-skin dance floor, flashing their wings, pairing up, mating, and laying their eggs. Emboldened, they start to nip at my legs. I regret not wearing pants. Another species of arthropod are also desperately clutching to the whale, simply because they have nowhere else to go. Whale lice. Thought not to be harmful, there are 29 species of these highly specialized and host-specific crabs which spend their lives tightly clutching whales’ skin folds with their claw-like legs, chewing off old skin. These lice were a gift from the whale’s own mother, who earned her lice from the mother before her. For this reason, these heirloom creatures have been helpful to scientists who use lice DNA to study whale population evolution. When a Right whale calf was found dead in 2004 with humpback-whale lice, researchers concluded that the calf was nursed by a humpback mother, if one could believe such a thing, because these lice spread through physical contact only. I peer closely at the lice, bleaching in the hot sun. They have almost no body and are all legs, dotting the dark skin like little stars, now dying as they lived. The pink ones are still alive, mourning for the untimely fate of the whale and, subsequently, their own. “You made it,” Rob says as he lumbers over, his teddy-bear frame filling his overalls. His curly hair is tufting out of the sides of his cap. Specks of shiny whale flesh are stuck to his pants. I ask if he has a hunch how the whale died. “I just focus on collecting the facts,” he answers. “Then I put all the facts together to come to a conclusion.” I inquire how long the whale is, and he states “930 centimeters,” which Ken’s phone charitably translates as 30.8 feet. Humpbacks grow to 45-50 feet, with the females stretching larger than the males. Rob goes back to calmly directing his volunteers, who are cutting sections of a rather neatly grown layer of white blubber. Blubber is not just flab. It is a unique kind of connective adipose tissue which is 60% fat, thicker and containing more blood vessels than the fat found in any other animal. Blubber is well-known for its insulating properties, but it has other functions. Blubber increases whales' buoyancy and is an important energy source for migrating whales, especially nursing mothers who fast for several months while living off of blubber for both the nourishment of themselves and their calves. The volunteers seem to be having more trouble than whalers did. “In whaler’s cases,” Rob explains, “they want the blubber. In our case, it’s in our way.” Whalers would typically use a giant blubber hook to unravel the blubber from the whale in long strips while the whale floated alongside the ship, like spiralizing the peel of a bobbing apple. Here, sections of blubber are hacked away in rectangular hunks and then peeled off to the side with hooks. The muscle underneath is light pink. “Can I help cut?” I ask, wanting the full experience. Hannah, a youthful-looking biologist for AMCS, answers in the same tone I use towards my 4 year old son when he asks to help make dinner: “These knives are really sharp,” she says, “but we can train you as a volunteer. If you give me your contact information, I can send you information.” I must look crestfallen, because she explains, “Look, I once almost sliced my finger off. It didn’t heal quite straight, but...” She holds her index finger up, wiggling its angled fingertip. I smile politely. I grab a pair of gloves and approach a cast-off piece of blubber. Surprisingly, it is simultaneously firm yet gummy, with a gelatinous surface which jiggles when I vibrate my finger. The surface sticks to my glove like silly-putty. Phew, I thought. When we have kids make goop at the museum and we tell them it’s whale blubber, we are not that far off. “Get a new knife,” I hear Rob instructing. “I just switched knives, and it cut into it like butter.” I am surprised how they face the same troubles as whalers on a whaleship, who would call out “another sharp one!” to a blacksmith or barrelmaker who would constantly sharpen spades for the crew during the blubber-stripping process. I walk around the whale’s body, respectfully quiet. I pass its eye. Its eyelid is partially open. Many people have shared that when you look into the eye of a whale, the experience is profound, even spiritual. When I met the gaze of a dolphin swimming sideways to look back at me on one whale watching trip, the feeling was transcendent. There is something there – a human-like consciousness perhaps - looking, feeling, and thinking back at you. And here, even dead and rotting on the beach, there was still something there behind that eye. As if on cue, Rob comes over. He plunges his knife into the side of the eye. Dark, thick juices hiss out, and – ploink! – out comes the eyeball. I swallow hard. “Left eyeball!” he calls out. A volunteer dutifully stumbles over the sand with a cutting tray, and like a good waiter, delivers the wobbling sphere back to the tent. I kneel by the whale’s face. Ken snaps a picture, cheering “Our fearless director!” The skin around its snout is mottled gray and white, with rounded tubercules protruding around the snout, like bumps on a pickle. To my astonishment, the biology books hold true: there, in the center of each tubercule, is one single, tiny, yellow hair. The single bristle feels stiff when I poke it with my finger. This tiny thorn is the very last speck of thousands of years of the evolutionarily shedding of whale fur, one hair at a time, a firm no-thanks to the stubbly genes that bind us bristly mammals. I now touch its skin. The surface feels like tire rubber. I move on to touch the bristles of baleen on its upper jaw. The baleen is a messy, interweaving network of keratinous fringe, thick and matted like a bird’s nest. The bristles feel like a tough broom. While I had taught for years how baleen filters food out of the water, I now fully understand how tiny shrimp are truly entangled and then swallowed. The smell is intensifying. The elation I expected to feel upon completing a highlight of my life – to touch a whale! - is being drowned out by the sick miasma pouring out. I continue to take shallow breaths and chew mint gum. I look over my shoulder and see Ken is smartly upwind. With the hot sun baking overhead, and bacteria reproducing by the trillions beneath the blubber, methane is building up, producing one of the worst smells nature has ever produced. This is what made whaleships the stinking rose of the nautical world, with ships downwind able to smell a whaleship before seeing one. Nauseous, choking smells were one of the top complaints of life on a whaleship. One seaman wrote in 1860: “It is as if the ill odors of the world were gathered together and being shaken up.” Whaler Charles Nordhoff described verbosely how one could not get away from the oily stench in 1856: "Everything is drenched with oil. Shirts and trowsers are dripping with the loathsome stuff. The pores of the skin seem to be filled with it. Feet, hands and hair, all are full. The biscuit you eat glistens with oil, and tastes as though just out of the blubber room. The knife with which you cut your meat leaves upon the morsel, which nearly chokes you as you reluctantly swallow it, plain traces of the abominable blubber. Every few minutes it becomes necessary to work at something on the lee side of the vessel, and while there you are compelled to breath in the fetid smoke of the scrap fires, until you feel as though filth had struck into your blood, and suffused every vein in your body. From this smell and taste of blubber, raw, boiling and burning, there is no relief or place of refuge." Suddenly a woman who looks vaguely familiar announces, “We have some bruising!” Dark hemorrhaging has spread around the area behind the flipper, as if someone spilled a giant bottle of crimson ink, possibly indicating a vessel strike. More pictures and samples are taken. Then she asks, “Who here has clean hands?” Just one volunteer raises a hand. “Can you lift my sunglasses and put them on my cap?” she asks, and finds something to wipe the sweat off her face. She is wearing a psychedelic-colored cap with the word Joy written on a green piece of masking tape fixed to the front side. Now I remember: I had met her from my couch as I watched her on PBS, dumbfounded as she explained how our vocal cords evolved from fish gills. She is Dr. Joy Reidenberg, a research scientist who specializes in comparative anatomy. Today, she is here as a volunteer. Her dark ponytail, streaked with silver, sticks out of the back of her cap. At one point she hollers loudly, “Did you do the genitals?” in the same tone one would ask a friend where they parked the car. Unlike other mammals, whales have elected to keep their procreative organs demurely hidden. All rules are off during mating season. Male Southern Right whales take the gold for the most highly endowed animal, whose prehensile-like phallus reaches an unprecedented 12 feet, helpful in breeding showdowns. Smartly, veins of cooled blood returning from the flukes are routed to the testes to keep sperm production chilled. Not to be undone, female reproductive gear is quite complex with a dizzying number of species-specific twists, turns, and angles that are still poorly understood. Still unwilling to sacrifice even an inch from being thoroughly streamlined, alongside each side of the female’s genital slit are two nipples, inverted when not actively nursing. Each can actually eject milk right into calves’ mouths in a thick, fatty, ribbon-like stream, helpful since calves can’t really move their lips.

I ask Joy a very important question: “How do you deal with the smell?” “What smell?” she answers incredulously. “This is nothing like dead sea turtle. That is bad. This is fresh! Fresh meat!” I gently place her sunglasses back on her face for her. While I try to conceptualize a smell worse than the one we are breathing in, Rob calls out helpfully, “I breathe through my mouth!” It has been a few hours now. Ken patiently waits, father-like, telling me, “When you’re done learning, you let me know. I’m checking emails,” - and to reassure me of his hard work - “See, I just disciplined someone!” Two members of the Coast Guard come to stare with appropriate disgust. Bottled water is passed out. I reflect on the irony of us drinking from single-use plastic bottles which are undisputedly choking the ocean while we examine this whale for evidence of human impact. I look at the whale’s tail in the sand, which feels surprisingly firm and stiff. There are no bones in whales’ tails; instead the flukes are made up of muscle and dense tissue. Besides for being used to propel a whale through the water, tails are used for lobtailing or tail slapping, thought to be a form of communication as well as defense. Arteries and veins in flukes help maintain the whale’s temperature. Southern Right Whales even use their flukes like sails: they lift their flukes into the wind to move through the water. Researchers rely on the color patterns, shapes, and scars on whale tails to aid with identification, just like human fingerprints. In the past few years, there has been a disturbing uptick in the number of sightings of Humpback and Gray whales who have lost this most quintessential part of their biology. Likely choked off by entangled fishing line, a consequence of industrial fishing which occupies a third of the planet, the majority of tailless whales are thought to eventually succumb to this fatal handicap. Astonishingly, there have been reports of plucky individuals who continue to survive, even on unimaginable migrations. The excavator is now called into service. We stand a respectable distance back. Flashes of YouTube videos showing whale carcasses exploding like geysers run through my mind. With directional waves of Rob’s hands, the pectoral fins are detached from their white sockets. The backhoe raises its giant metal jaws, like a T-rex above a kill, and starts to peel back the lower jaw. We hear a popping sound of released gas. “There it goes,” Ken says. “Try not to cut the larynx!” Joy calls. Ken watches the backhoe carefully. “He’s good,” he evaluates the operator. As the jaw is lifted, Ken calls out, “If the jaw swings, won’t it hit the tent?” “No!” Rob hollers back reassuringly. “It would hit me!” Rob and Joy continue to cut alongside the whale, slicing through tendons and muscles as the backhoe continues to peel the whale apart, helping the whale to split. The massive, cushiony gray tongue spills out of its mouth, like overturned dark Jello. Rob explains that the tongue itself can weigh over a ton. Dark rivulets stream out from under the whale and pool in the sand. “Do whales have taste buds?” I wonder out loud. “There’s evidence for taste buds in some dolphins,” Rob answers. Salt seems to be whales’ primary taste; the other taste buds have atrophied away. While this sounds like a pitiful way to eat, no whale chews its food, so they likely don’t care too much about what they’re missing. Whale tongues are a prized delicacy for orca whales, who will viciously attack whales in teams and then feast on the tongue first. There is even a mutualistic story of a pod of killer whales who teamed with whalers near Australia bring down whales for a chance to eat the tongue. The upper jaw is cast to the side. “Wouldn’t you like that?” Ken whispers about the fringed baleen. “For the museum? Imagine he says you can have it. Now what do you do with it?” Not only would I have to figure out what to do with half a whale head, but I have to figure out what to do with the whale palate in the museum that I now realize is ceremoniously displayed upside down. Who would have thought the center of a whale’s palate grooved inward at its center, and was not domed upwards like ours? I then notice something oddly strange taking place. I blink my eyes. The cut pieces of whale are a sickly green. They weren’t green a few minutes ago. Is it my imagination? Am I being blinded by the sun? Joy explains, “It’s exposed to oxygen, and it’s rotting.” Now I see why whalers truly had to process whales immediately, even – to the dismay of whaling wives – on the Sabbath. Because of the insulating properties of blubber, whale flesh decays extremely rapidly. Joy now steps into the spilled organs of the whale. Her boots disappear into swirled guts. Volunteers pull their shirt collars up over their faces to block the stench. Ken takes a look, proclaims “Disgusting!” and walks back to the side. A volunteer is behind her, ready to catch her if she starts to slip. She reaches within the spinal cord, trying to feel for the brain. “Nothing!” she says. Just recently dead, and the brain has already decayed into liquid. They are examining the lungs and the stomach, which sadly turns up empty instead of full of bunker, the fish that is drawing more and more Humpbacks to the area. I want to stay and see the rest of the organs, but I surrender to my own mammalian need to pump milk for my own little human calf at home, who is wearing a onesie with a smiling whale on it. Ken leaves instruction not to dig the ten-foot deep hole for the whale until the entire necropsy is complete. Burial is the most natural and practical way to let nature take care of the whale. We leave as the lower intestines are spilling out, which are cream-yellow and kinked like giant sausage. When we get back into the car, we wrinkle our noses. “Ken -- do we smell?” I innocently ask. Because the odors are oil-based, the smell is slow to dissipate. If only we knew that ten minutes later, his typically reverent employees would be vocally throwing him out of the office, demanding he take a shower before returning. I finally drive myself home with both the AC on high and each window fully down, barely able to stand myself. I need to make a stop at a store, but decide I’m not fit to be around people. If we had only observed the necropsy and smell like death, my eyes cross to think how bad the people actually performing the task smell - and how bad whalers themselves smelled, who could not decently wash for years. I feel refreshed after a hot shower. My husband complains the bathroom still smells, and silently banishes my sneakers to the front porch. At the end of the day, I check the AMSC’s Facebook feed: "The necropsy examination showed that the whale had not been actively eating and may have been sick. Samples are being sent to a pathologist to help determine a cause of death, and results may take several months to come back." I look at the posted picture of the whale before the necropsy started. My eyes now see a complex machine through the tough skin - tendons, muscles, blood, innards. Three days later, Ken texts, “My car still smells, slightly.” My shoes are still cast outside of the house, forlorn. Ken adds, “I’m going with the story that you stunk worse than I did. I spent a large amount of time upwind.” I try to relate the greatness of the necropsy to my wincing museum team - “the blubber! the stink!” - as they cover their noses in empathy. My mother texts please don’t send any more pictures. My sister says I’m throwing up just thinking about it. But I remember what Long Island ornithologist and museum founder Robert Cushman Murphy wrote in his diary on October 10, 1912 when he observed his first whalehunt: “This has been the most exciting day of my life.” While I observed no hunt and only whale, I know he’s not making it up. What do I do if I see a whale on Long Island?

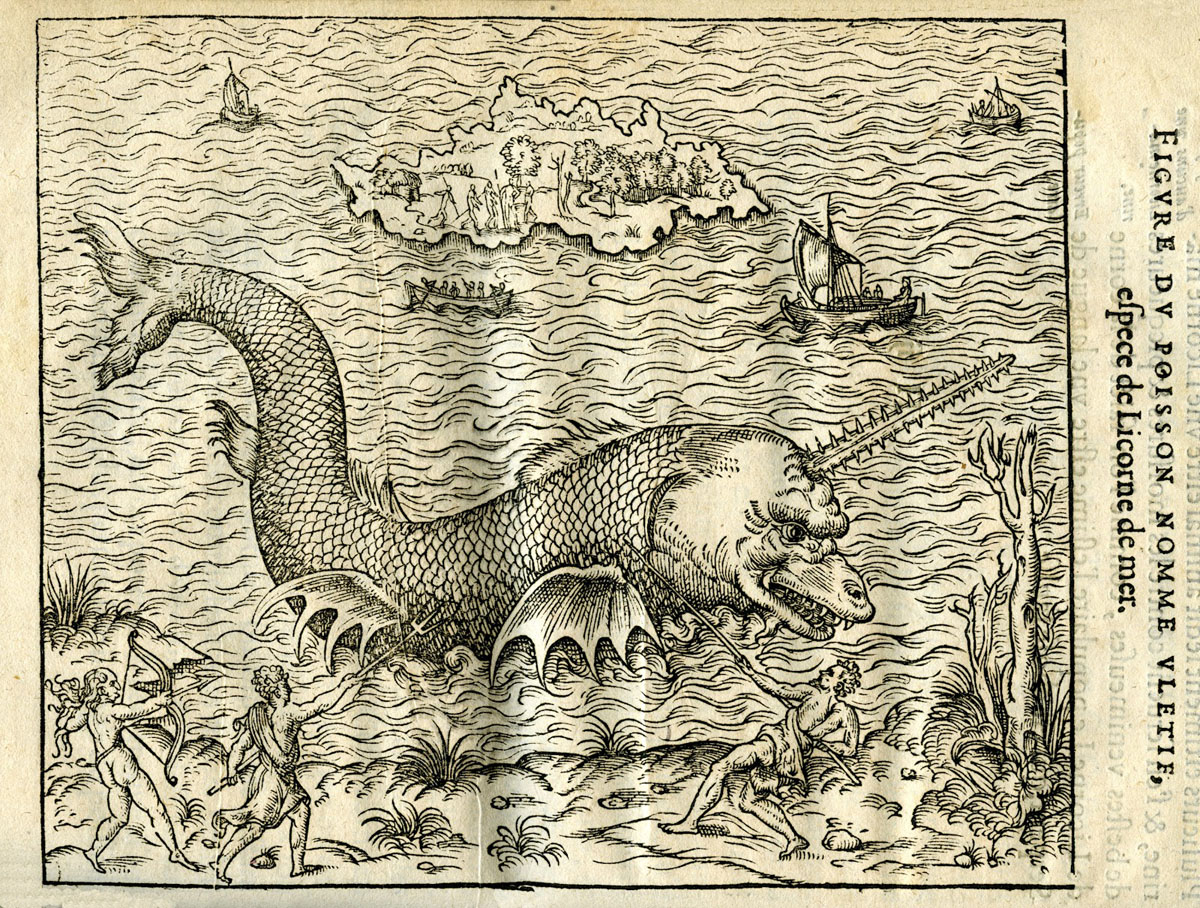

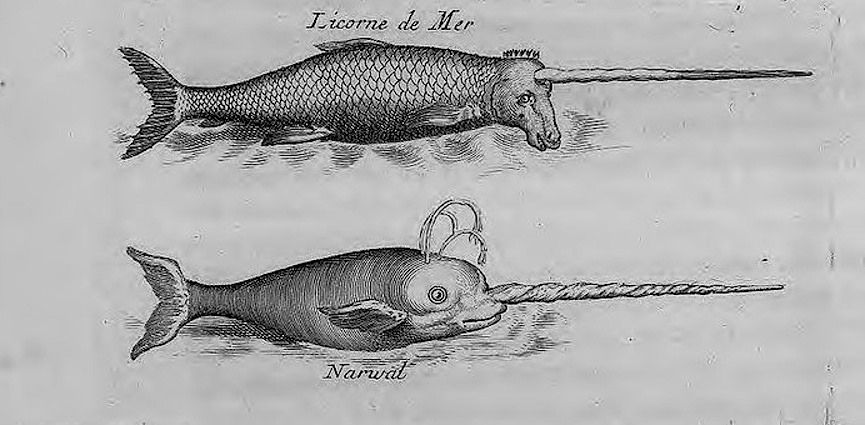

By Brenna McCormick-Thompson, Museum Educator  From Goldsmith's History of the Earth, 1807 From Goldsmith's History of the Earth, 1807 Every year, the Whaling Museum conducts outreach programs in schools and libraries across Long Island. Our educators pack up some of the museum’s most interesting artifacts and travel to share them with kids from Queens to Riverhead. Of the many items we bring - antique compasses, battle-worn harpoons, glittering deck prisms, and fear-inspiring megalodon teeth - few are as popular as a small, delicately spiraled segment of whalebone: the very tip of a narwhal tusk. This tusk is actually a tooth, which most male (and very rarely female) narwhals grow out of the front of their heads. The purpose of these elongated teeth is not definitively known, and is still hotly debated among the scientists who study these small arctic whales. Of all whales, the narwhal in particular has always been rather mysterious. Gathering information about these creatures, never mind even locating them, has always been a tricky business since they spend their lives hidden away in deep, dark arctic seas under thick layers of ice. It’s perhaps this aura of mystery that makes the narwhal the perfect alter ego of one of the most popular mythical creatures: the unicorn. Even for kids who recognize the tusk for what it is, the thrill of holding a “real” unicorn horn is palpable...and rather curious. How did the enlarged canine of an isolated species of arctic whale come to be so fundamentally associated with a magical horned horse? To uncover the origins of the unicorn myth, we have to travel back to Ancient Greece. In the 4th Century BCE, Greek physician Ctesias was travelling through Persia when he heard tales of an exotic land beyond the Indus River. Captivated by the accounts he heard of the strange beasts and curious peoples who inhabited the land we now call India, Ctesias took it upon himself to record these wonders for audiences back home. The resulting work, Indica, was an odd compilation of faithfully recorded descriptions of contemporary Indian beliefs and customs, and fanciful portraits of astonishing creatures. Among the latter is an account of the “wild asses in India the size of horses and even bigger.” Ctesias writes that these animals “have a horn in the middle of their brow one and a half cubits in length. The bottom part of the horn for as much as two palms towards the brow is bright white. The tip of the horn is sharp and crimson in color while the rest in the middle is black. They say that whoever drinks from the horn (which they fashion into cups) is immune to seizures and the holy sickness and suffers no effects from poison.” The creature described by Ctesias, which the Greeks came to know as monoceros (one-horned) and which later the Romans called unicornus, was most likely an Indian rhinoceros. Having no exposure to such an animal, and with only the words “asses” and “horses” to serve as a guide, subsequent ancient and medieval scholars struggled for centuries to describe this seemingly fantastical beast. Consequently, the unicorns depicted in early bestiaries are patchwork creatures - curious combinations of lions, goats, and deer - always vaguely equine in nature, but never the gleaming white horse we’ve come to know. The most striking difference between ancient and modern unicorns is the horn itself. Early unicorns were often given smooth, curved horns, surprisingly reminiscent of rhinoceros tusks. Though the creators of these images had undoubtedly never seen a rhinoceros in person, it’s possible that they may have come across the horn of one of these animals posing as a unicorn relic. This image of the unicorn seemed to change as narwhal tusks were gradually introduced into the European market. Appearing first in northern regions, these tusks were possibly distributed by the Viking sailors who were among the only people to venture into the arctic realms of these whales. These elegant, pale horns so captured the medieval imagination that the concept of the unicorn changed to better correspond to these strikingly beautiful artifacts. Unicorns transformed from beastly hybrid monsters to graceful beings who were so pure of spirit they could only be tamed by the fairest of maidens. Legends and artwork featuring the new, refined unicorn exploded across the continent, all but obliterating any memory of the fierce Indian beast from which the myth originally came. By the time Marco Polo embarked on his travels through Asia towards the end of the 13th Century, the notion of the gleaming, white unicorn was so absolute, that it was with great confusion and disappointment that he proclaimed “'Tis a passing ugly beast to look upon, and is not in the least like that which our stories tell of as being caught in the lap of a virgin; in fact, 'tis altogether different from what we fancied.” Little by little, Europeans recognized that their concept of the unicorn was inspired by two very real, very different creatures. Though both the rhinoceros and the narwhal have since left the realm of legend and progressed into the world of science, each animal retains echoes of their mythic pasts. The horn of the Indian rhinoceros (whose Latin name is appropriately Rhinoceros unicornis) is tragically still valued for its alleged medicinal properties. As for narwhal tusks, they seem to have retained the aura of mystery and magic that so deeply enthralled so many people centuries ago. Though it’s clear that these whales were not the original inspiration for the unicorn myth, we certainly have their stunning tusks to thank for transforming unicorns into the magnificent creatures we know today.  Brenna brings a wealth of maritime knowledge to the Whaling Museum. She wrote her dissertation on the Representations of Collective Memory and National Identity Aboard the Cutty Sark while at Georgetown University. With an MA in Global History and experience teaching at the Westchester Children’s Museum, she is especially adept at interpreting museum artifacts for education programs involving a wide array of age groups and learning styles.

Mulford Farmhouse is one of the oldest in Suffolk County. Mulford Farmhouse is one of the oldest in Suffolk County. Before George Washington, Paul Revere, and Alexander Hamilton, the first – and feistiest! - patriots were none other than Long Island whalers. The first colonists were English Puritans who arrived to the east end in 1640. At the time, the area was considered an extension of Connecticut and New England – seen as remote and separate from the Dutch-ruled western end of Lange Eylant. These pioneers were initially farmers, but they quickly became seasonal entrepreneurs after they noticed their enormous marine neighbors spouting by their shores: blubber-rich Right whales. Whaling companies were launched during the winter months, hunting whales in rowboats on frigid beaches with the labor of local Native Americans. In large iron trypots on the sand, whaling crews stewed blubber until it melted into liquid gold - whale oil. Whale oil was used chiefly for illumination (and later in time, for a variety of manufacturing purposes). Oil even served as a currency; local schoolteachers were paid in whale oil. For the next twenty years, colonists worked to perfect this trade. Whaling quickly became part of community life, with required whale-spotting shifts from able-bodied men. School even let out from December to April so children could help spot and process whales. Oil was shipped to New England rather than New Amsterdam to avoid Dutch taxes. This trade route was suddenly halted when new commerce rules were set in place by England. The entire Long Island was now a part of New York. All goods were to be exported through New York City. The whale was a “royal fish,” from which the crown demanded a twenty to fifty percent tax. East-enders were horrified. The battle between whalers and England began. Whalers were outraged at taxation without representation – foreshadowing the defiant Boston Tea Party a century later. Whalers rebelled by turning Long Island into a smuggler’s haven, avoiding taxes by continuing to ship their oil to Boston or New London. A string of upset New York governors tried to enforce the tax – generally unsuccessfully. When the Duke of York investigated how many whales were caught in the past 6 years – and what his share was – he found no records had been kept. Lord Cornbury, a later New York Governor, whined that “the illegal trade” was still carrying on between Long Island and New England. With colonists’ protests falling on deaf ears, the towns of East Hampton, Southampton, and Southold bypassed the Governor of New York and submitted a petition to the court of England to be made a free corporation or continue under Connecticut rule. Their detailed list of complaints is similar to the tune of complaints in the Declaration of Independence. Their plea was denied. Their solution? Ignore the whale tax anyway. Colonists continued to smuggle the majority of oil to New England. New York merchants themselves were also flouting the law, which required all international trade to go through England. Instead, they traded directly with the West Indies, exchanging whale oil for rum, sugar, and cocoa. Taking international trade into their own hands, New Yorkers who felt particularly courageous loaded up their ships and sailed with their goods to Madagascar, where there was an anarchist colony of none other than – pirates! Doing business with pirates was highly profitable, since it was all tax free. An inspector noted that in 1695, Long Island “was a receptacle for pirates and the people generally a lawless and unruly set.” Whalers continued to protest. One of the pluckiest whalers who objected to the tax was Samuel Mulford of East Hampton, who lived from 1644-1725. He was a bold and somewhat quirky fellow. He championed the cause of the whalers, himself a financially successful owner of a whaling company of 24 men. Elected as a representative to New York Assembly in 1683, he was expelled from the assembly twice for his outspoken demands; colonists simply re-elected him and sent him back. When he sailed to London to protest the whale oil tax, he sewed fishhooks in his pockets to deter pickpockets during his long wait outside Buckingham Palace. Ultimately, the Crown eased taxation. Mulford didn’t get to see this victory, as this announcement came five years after his death. Encouragingly, various acts were passed by the British Parliament to support the lucrative whaling industry, but colonists’ frustrations towards their relationship with England never really went away. During the Revolutionary war, which brought whaling to a standstill, locals repurposed whaleboats for guerilla warfare against British efforts. After American won its independence, a new era opened for whaling. In 1785, the Lucy left Sag Harbor to whale offshore Brazil; she returned with an unprecedented 360 barrels of whale oil. Americans took notice. To encourage trade, George Washington then authorized the first lighthouse in New York State to be built, the Montauk Lighthouse. The hundreds of whaleships that followed the Lucy would have sailed home from their global voyages directed by this lighthouse - illuminated by none other than whale oil. More: Learn about Long Island whaleboats used in the Revolution ► Learn More

By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director As you reach for a sweet treat this June in honor of National Candy Month, consider how the abundance of candy today is a rather exceptional thing. For much of human history, sugar was an expensive indulgence reserved for celebratory desserts. Sugary treats were a luxury for the rich. People also used sugar for therapeutic functions, with early candy serving as a form of medicine, including lozenges for coughs or digestive troubles. Sugar was also used as a preservative; similar to salt, sugar dried fruits and vegetables, preventing spoilage. But all in all, sugar was carefully conserved. In George Washington’s time, the average American consumed only 6 pounds of sugar a year (far less than the 130 or so pounds consumed annually per person today). The use of sugar swelled dramatically in 1800’s. Suddenly, sugar was everywhere, and with it came new technological advances in candy production. Sugar shipped from slave-powered plantations in the West Indies became more affordable and available with new, steam-powered industrial processes. These changes were part of the Industrial Revolution, made possible by prized whale oil and its valuable lubricating properties. In 1830, Louisiana had the largest sugar refinery in the world. The invention of the Mason jar in 1858 drove demand for sugar for canning, and in 1876, the Hawaiian Reciprocity Treaty made sugar even more available. People couldn’t get enough of sweetness. The availability of sugar brought a slew of new inventions to the culinary scene: candy! Confectioneries sprang up everywhere. The shops’ best customers were children, who spent their earnings on penny candy. Hard candies became very popular. As Yankee whaling reached its peak, Victorian-era sweets boomed with a succession of creations: the first chocolate bar was made in 1847; chewing gum followed in 1848; marshmallows were invented in 1850, and in 1880, fudge. People’s breaths were taken away when sweets with soft cream centers were tasted at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. Some candies, especially hard ones, were sold as being ‘wholesome’ and even healthy. Unfortunately, candy was anything but nourishing. Sugar was sometimes adulterated with cheaper Plaster of Paris or chalk. Other candies were far more toxic. In 1831, Dr, William O’Shaughnessy toured different confectionery shops in London and had a range of dyed candy chemically analyzed; he found a startling number of sweets colored with lead, mercury, arsenic and copper. But as ubiquitous as candy was on land, a sweet treat was quite rare at sea, especially on a whaleship. Sugar on board was a still a luxury reserved for the captain and officers. The crew had to settle for molasses, which was often infested; one whaler wrote it tasted like “tar.” Candy only makes brief glimpses in whaling logbooks, or daily records. On May 22, 1859, William Abbe journaled on the ship Atkins Adams: “Cook & Thompson Steward making molasses candy in galley.” (Earlier on the voyage, he described molasses kegs as “the haunts of the cockroach.”) Laura Jernegan, a young daughter who sailed with her father and family on a three-year whaling voyage, wrote in her diary on board the Roman, “Feb 16, 1871. It is quote pleasant today. The hens have laid 50 eggs…” Then, an exciting thing happened – she passed another whaleship at sea, the Emily Morgan. There was a whaling wife aboard, too! Laura wrote: “Mrs. Dexter [the wife of Captain Benjamin Dexter] sent Prescott [her brother] and I some candy.” In other cultures, whales still facilitated the treat scene – no sugar needed. Frozen whale blubber was (and is) a traditional treat for the Inuit and Chukchi people. Called muktuk, cubes are cut from whale skin and blubber and conventionally are served raw. While whaling in our country is a thing of the past, the years of unrestricted whaling reflect how, in essence, people treated the ocean “like a kid in a candy store,” as noted by author Robert Sullivan. In the 20th century, so many whales were caught so quickly and efficiently that soon even whalers themselves were worried about saving the whales. Today, as we continue to gather resources from the sea, we must ensure the ocean can replenish itself faster than we can sweep its candy off the shelves. Bring Candy History into Your Kitchen

By Nomi Dayan Whaling was a risky business, physically and financially. Life at sea was hazardous. Fortunes were made or lost. Whalehunts were perilous, as was the processing of the whale. Injuries were rampant and death was common, sometimes on nearly every voyage. In some instances, the deceased was none other than the captain. Captain Sluman Lothrop Gray met his untimely end on a whaleship. Born in 1813, very little is known of his past, his family, or his early experiences at sea. In 1838, he married Sarah A. Frisbie of Pennsylvania in the rural town of Columbia, Connecticut. His whaling and navigational skills must have been precocious, because in 1842, in his late twenties, Gray became a whaling captain – and a highly successful one. His wife, Sarah, joined him in his achievements, living with him at sea for twenty years. Three of their eight children were born during global whaling voyages. Gray commanded a string of vessels: the Jefferson and Hannibal of New London, CT to the Indian and North Pacific Oceans, the Mercury and Newburyport of Stonington, CT to the South Atlantic, Chile, and Northwest Pacific Oceans, and Montreal of New Bedford, MA to the North Pacific Ocean. While financially successful, Gray’s crew felt his harsh personality left much to be desired. Some of his blasphemies were recorded by a cabin boy on the Hannibal in 1843. He did not hesitate to flog crew members for minor mistakes. Unsurprisingly, when Sarah reported her husband had taken ill, the crew rejoiced. (To their chagrin, he recovered.) As Gray aged, he attempted to retire from maritime living and shift into the life of a country gentleman. He bought 10 acres of land in Lebanon, Connecticut and lived there for 7 years, where his house still stands. This bucolic life did not last, and Gray returned to whaling. With his wife and three children – Katie, Sluman Jr., and Nellie aged 16, 10, and 2, he sailed out of New Bedford on June 1, 1864 on the James Maury. Built in Boston in 1825 and sold to New Bedford owners in 1845, the James Maury was a hefty ship at 394 tons. Gray steered the course towards hunting grounds in the South Pacific. Unexpectedly, after nine months at sea in March 1865, he suddenly became ill. The closest land was Guam - 400 miles away. Sarah described his sickness as an “inflammation of the bowels.” After two days, Captain Gray was dead. The first mate reported in the ship’s logbook: “Light winds and pleasant weather. At 2pm our Captain expired after an illness of two days.” He was 51 years old. Sarah had endured death five times before this, having to bury five of her children who sadly died in infancy. She could not bear to bury her husband at sea. Considering how typical grand-scale mourning was in Victorian times, a burial at sea was anything but romantic. It was not unheard of for a whaling wife to attempt to preserve her husband’s body for a home burial. But how would Sarah embalm the body? Two things aboard the whaleship helped: a barrel and alcohol. Sarah asked the ship’s cooper, or barrelmaker, to fashion a cask for the captain. He did so, and Gray was placed inside. The cask was filled with “spirits,” likely rum. The log for that day records: “Light winds from the Eastward and pleasant weather; made a cask and put the Capt. in with spirits.” The voyage continued on to the Bering Sea in the Arctic; death and a marinating body did not stop the intentions of the crew from missing out on the summer hunting season. However, there was another unexpected surprise that June: the ship was attacked by the feared and ruthless confederate raider Shenandoah, which prowled the ocean burning Union vessels, especially whalers (with crews taken as prisoners). The captain, James Waddell, had not heard – or refused to believe - that the South had already surrendered. When the first mate of the Shenandoah Lieutenant Chew came aboard the James Maury, he found Sarah panic-stricken. The James Maury was spared because of the presence of her and her children – and presumably the presence of her barreled husband. Waddell assured her that the “men of the South did not make war on women and children.” Instead, he considered them prisoners and ransomed the ship. 222 other Union prisoners were dumped onboard the ship and sent to Honolulu. One can imagine how cramped this voyage was since whaleships were known for anything but free space. A year after the captain’s death, the remaining Gray family made it home in March 1866. The preserved captain himself was shipped home from New Bedford for $11. Captain Gray was finally buried in Liberty Hill Cemetery in Connecticut. His resting place has a tall marker with an anchor and two inscriptions: “My Husband” and “Captain S. L. Gray died on board ship James Maury near the island of Guam, March 24, 1865.” Sarah died twenty years later, and was buried next to her husband. It is unknown if Gray was buried “as is” or in a casket. There are no records of Sarah purchasing a coffin. Legend has it that he was buried barrel and all. Nomi Dayan is the Executive Director at The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor, NY. Read More:

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed