"I THINK I AM QUITE A SAILOR." Charlotte DEHART

|

Whaling Wives Were Pioneers

The saga of hunting whales was unquestionably viewed as man’s world. “It is no place for a woman,” wrote Captain James Haviland on the Baltic in 1856, “on board of a whaleship.”

The Whaling Museum's special exhibit, Heroines at the Helm, explores how whaling wives pushed gender roles in two major ways:

<

>

Not all women sailing on whaleships were captain’s wives.

<

>

“It doesn't seem much like the Fourth of July, up here.” Eliza Williams, 1859 “I don’t believe if you was home on Christmas and I at sea that you had any better dinner than I did. We had roast turkey just as tender and nice as it could be besides vegetables, oyster stew, and mince pie.” Eliza Edwards, 1860 “We sat down to a Christmas dinner… at the sign of a right whale, lowered the boats.” ary Lawrence, 1857 “Oh, such dismal days are appointed to me. Another New Year has dawned upon us and we are far from home and friends.” Lucy Smith, rounding Cape Horn

<

>

“Sewing is my favorite employment especially at Sea when it enables me to pass away many an hour pleasantly that would otherwise pass tediously.” Mary Rowland

|

Spotlight On...

Having seen very little of her husband during the first 9 years of their marriage, 29-year old Mary Lawrence sailed with her husband and 5-year daughter, Minnie, on the Addison in 1856. Her journal reveals her deep trust in God to see the ship past danger, and at no point does she question her decision. She even filled her daughter’s doll buggy with Bibles and sent her daughter to give them out to the crew. She loved watching the ocean: “It is grand beyond anything I ever witnessed, sublimity itself.”

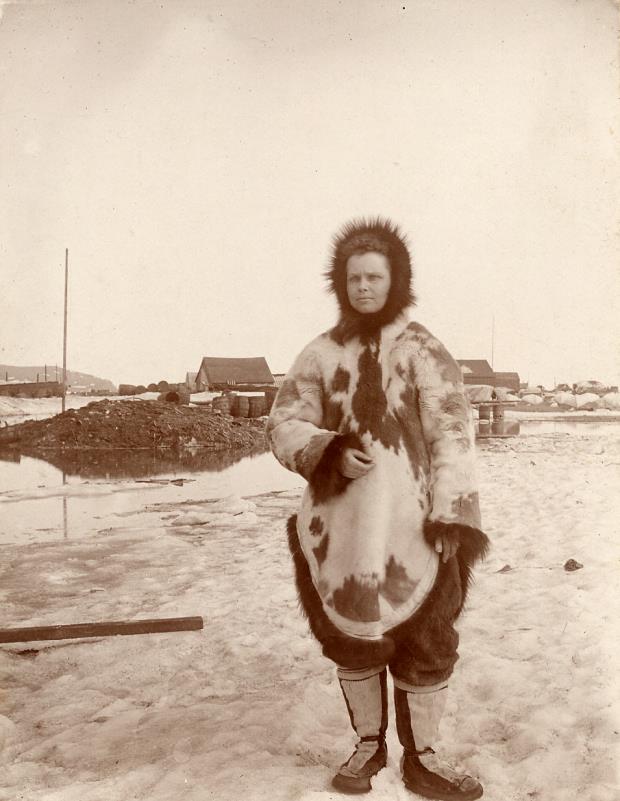

Viola Cook first sailed with her husband John in 1893, enduring nine long winters in the Arctic. At the start of Viola’s first voyage, she weighed 93 pounds, and returned 130 pounds from the effects of inactivity. With other wives there, she went sledding and staged elaborate dinners. On later trips, she had no female companionship, and on her ninth winter, she suffered from scurvy. She refused to sail again. Shocked at her disloyalty, John built a brig and named it Viola to persuade her to sail. His ploy worked, but she suffered from beriberi. After that, she never sailed again—fortuitous because the Viola sunk on its next voyage, and all hands, including a wife and 5-year old daughter, were lost.

Caroline Benedict Rose (1823-1901) was called the “Belle of Southampton” for her cultured manners, brilliance, and good looks. Although many questioned her judgement, she joined her husband, Captain Jetur, on three whaling voyages beween 1853-1871. She gave birth to her only child, Emma, in Honolulu in 1856, who logged thousands of miles in her childhood. The cabin boy called Caroline and Jetur “the finest people he had ever met.”

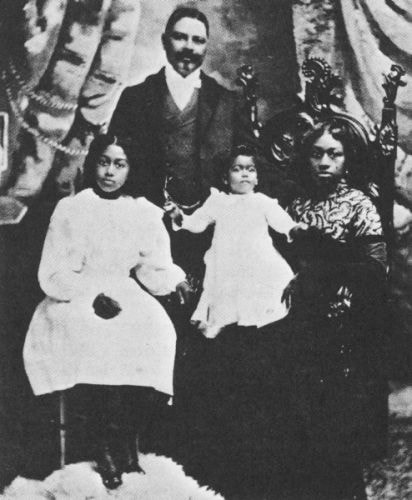

Julia Ann Shelton was the talented daughter of a leading black family in San Francisco, where she met her husband, William Shorey, the only black captain on the west coast at the time. She spent her honeymoon on his next whaling voyage, and would continue to sail with her children. She poses here with her family at the turn of the century.

Sarah A. Frisbie lived with her husband Sluman Gray at sea for twenty years. Three of her eight children were born during voyages (five of whom died in infancy). A resourceful woman, the steerage boy noted how “Mrs. Gray gathered a kind of tea that grows wild” in the Falklands and “went afishing and agunning,” feeding them all with fish and 16 rabbits. When she objected to Sluman’s blasphemies on the Hannibal in 1849, “the most profane language ever heard from mortal lips,” he told her to go below where she would not hear it. He died at sea on that voyage. With land 400 miles away, she preserved his body in a barrel of rum and shipped him home to Connecticut for burial.

Abby Jane Morrell of Connecticut pioneered the cause of whaling wives when she abandoned patience and demanded to sail with her husband in 1829. At the age of 15, she had married Benjamin in a flash ceremony the day before he sailed with a “chaste parting kiss,” with the Captain intending to return to a “full-blown flower.” A few years later, he hesitantly agreed to take her sailing two days before the voyage. On the trip, she and 11 men fell ill with cholera. Benjamin paced the deck fraughtfully, too mortified to pull into port for medical help, reflecting “that some slanderous tongues might attribute a deviation from my regular course solely to the fact of my wife’s being on board. No! perish all first!” He medicated the crew himself with “blisters, friction and bathing with hot vinegar.” Two men died, the rest recovered, and his reputation was safe.

If you were a whaling wife, would you sail with your husband, or stay at home? Created with PollMaker “What a bother clothes are, either to make or take care of! Without the fuss of them, how much time there would be for reading, study, and thought.”

Harriet Allen, 1870 |

|

Charity Norton of New Bedford passed Cape Horn six times, sailing with her husband on every one of his voyages, the first being in 1848. According to legend, the ships owners requested her presence to soften her husband’s personality, who one seaman said was “the hardest of the lot.” When she saw him preparing to whip crew members for trying to desert, she said, “John, what is thee doing?” He said, “Just giving them a few licks.” She said firmly: “John, thee is not.” And he didn’t.

|

Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor joined her husband at sea in 1857. She lived in Hawaii for several years while the crew continued to the Arctic. In the boarding-house, she became close friends with women in similar circumstance, writing long descriptive letters about Hawaiian life to her family. One day she and 3 other wives bravely went swimming together, holding hands “and such a nice time as we had, the way we danced around in the water & enjoyed it is better realized than described.”

|

Over the course of 10 voyages, Marian Smith (1866-1913) was an advanced navigator, log keeper, photographer, correspondent, and business partner of the Josephine. She even taught navigation to the boatsteerer, who grew to become a captain himself. Particularly spunky, she challenged another whaling wife, Honor Earle of the Charles W. Morgan, to see whose voyage by the difficult Crozet Islands would be most successful. A headline in the Boston Globe in 1907 ran Women Rivals Navigate High Line Whalers. Marian won.

|

This online exhibit was partially funded by the National Maritime Heritage Fund.