Culture

What's in a Seal?

|

The tribe’s official seal was designed by Shinnecock artist David Martine. The seal depicts the history of the Shinnecock, the People of the Shore.

It includes:

|

Reclaiming Roots

|

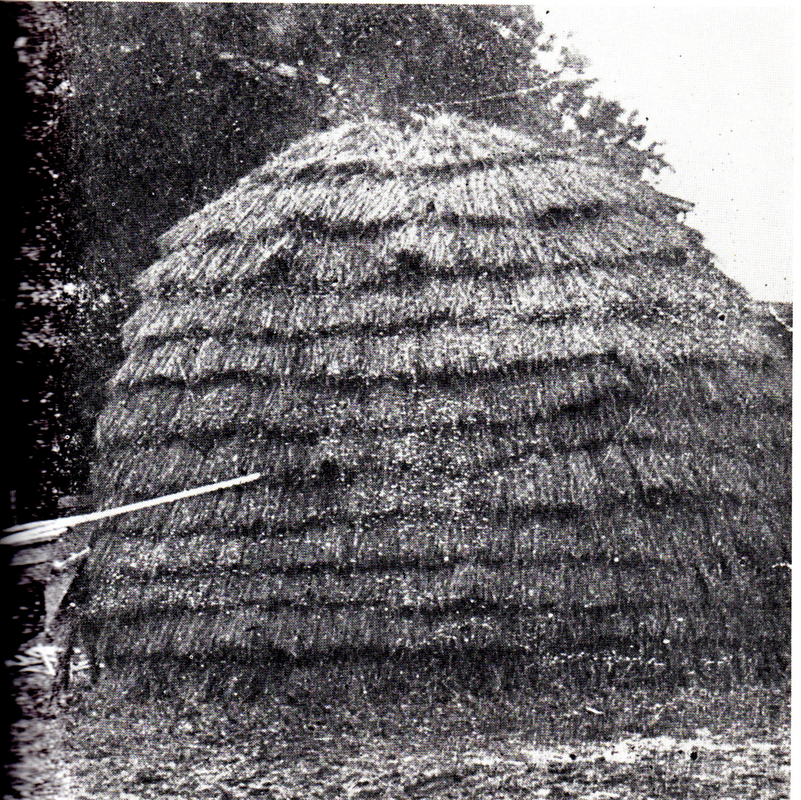

Shown here is a traditional Shinnecock dwelling around 1890. Up through the 1840’s, some Shinnecock still used these dwellings, as well as timber-framed houses. There are only two known historic visual records of a traditional Native American, pre-European-style home on Long Island.

This wigwam, or witu, would have been made originally with white cedar poles, bent and tied into a frame with inner bark cordage, with overlapping rows of meadow or sea grass thatched or sewn on with a large bone needle or wood needle or awl. Other styles of wigwams were covered with cattail reeds woven into mats, as well as tree bark. -- Beverly Jensen, Shinnecock Member |

Courtesy David Martine

|

|

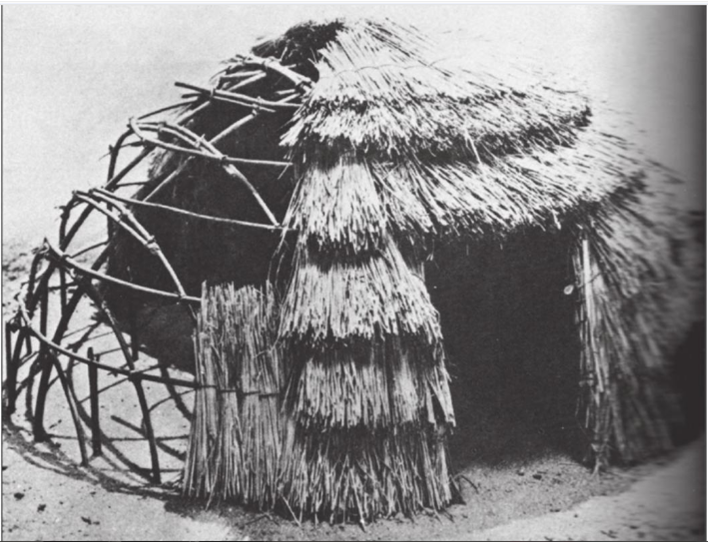

Compare the wigwam in this 1920 photo to the other photos of wigwams, taken just 30 years earlier.

This wigwam does not bear resemblance to older Shinnecock wigwams, where grass was tied together in bunches. What is important about this photo is the attempt of the individuals here to reconnect with their Shinnecock heritage. Left to right: Addie Cogsbill, Emma Bunn, Rose Kellis Williams, Anna Kellis, Mrs. Cuffee, and Adela Santoya. |

June Meeting

Do you take part in a celebration that merges beliefs?

|

The continuation of an ancestral celebration.

June Meeting, today held on the first Sunday in June, is a large gathering celebrating the renewal of life and emergence of the first plants. In 1901, Charles Bunn, a Shinnecock elder, said June Meeting was originally "the Feast of the Moon of the Flowers." The flower theme, symbolizing the rebirth of plant life after the winter, played a central role in the ceremony. A gateway to the integration of Christian beliefs. The Shinnecock, who resisted conversion to Christianity until the latter half of the eighteenth century, were introduced to the new religion within the context of June Meeting. Early missionaries were unsuccessful, mostly because of the language barrier. No further missionary activity was undertaken until after the American Revolution, when the Reverend Paul Cuffee, a Shinnecock convert, began to preach to his people. Cuffee overcame the resistance to conversion by gradually integrating Christian themes into aboriginal ceremonies. He began to preach at June Meetings, with considerable success in winning converts. -- Dr. John Strong, Historian |

Weaving Masters

The Shinnecock used woodsplints to create wicker-plaited baskets and fishing traps.

The sale of woodsplint basketry helped native people find new ways of making a living by selling lightweight containers.

The sale of woodsplint basketry helped native people find new ways of making a living by selling lightweight containers.

Images Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian

An Artist's View

David Bunn Martine is a Shinnecock artist specializing in painting indigenous scenes using figures against landscape realism. Here, Martine visualizes colonial-era Shinnecock life.

Courtesy David Martine. © David Martine

The Shinnecock Language

The Shinnecock are Algonquian—meaning they are tied to a native language group. (This is distinct from the Algonquin tribe of Canada.)

The Shinnecock language has not been spoken fluently for over a century. When Thomas Jefferson visited Brookhaven in 1791 and created an Unkechaug word list (a neighboring tribe of the Shinnecock), he wrote that even then, only three old women could speak their language fluently.

Today, the Shinnecock are eager to reconnect with their language. There has been progress reviving this dormant language by piecing together words from a translated Bible, deeds, historic documents, tribal records, and recordings.

The Shinnecock language has not been spoken fluently for over a century. When Thomas Jefferson visited Brookhaven in 1791 and created an Unkechaug word list (a neighboring tribe of the Shinnecock), he wrote that even then, only three old women could speak their language fluently.

Today, the Shinnecock are eager to reconnect with their language. There has been progress reviving this dormant language by piecing together words from a translated Bible, deeds, historic documents, tribal records, and recordings.

Learn a Shinnecock Word

Of the more than 300 indigenous languages spoken in the United States, only 175 remain, according to the Indigenous Language Institute.

Of the more than 300 indigenous languages spoken in the United States, only 175 remain, according to the Indigenous Language Institute.

|

|

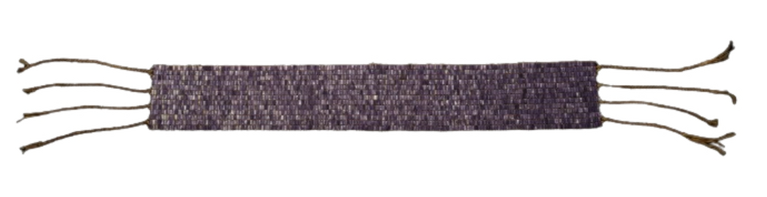

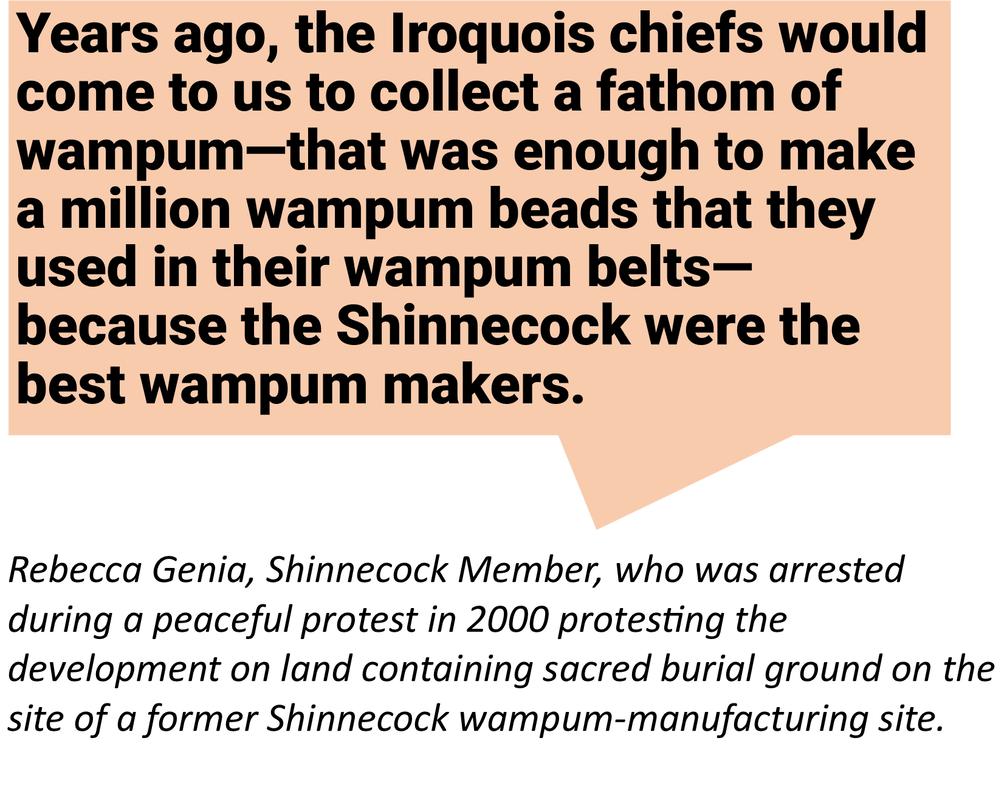

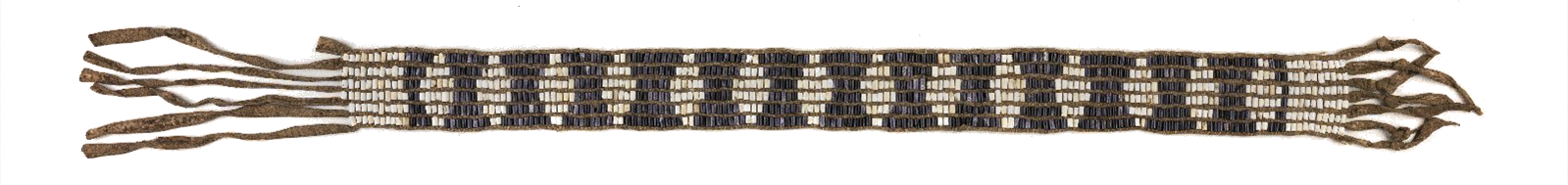

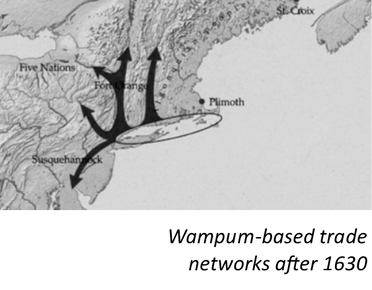

Wampum

A politically and spiritually significant medium.

|

How is wampum produced?

The Shinnecock, along with other native peoples, produced small white and purple beads laboriously crafted from the plentiful shells of the Quahog clam and whelk found on Long Island’s shores. Native artists today continue this tradition. How was wampum traditionally used? Wampum was used to pay tribute as a symbol of prestige and peacemaking, and was also used as ornamentation in jewelry. Diplomatic messages about intertribal relations and agreements were spelled out in wampum. The English modified the word wanpanpiag into wampum. Was wampum seen as money? As a sacred medium of ritual exchange, wampum had value as a trade item, but it was after European settlement that wampum was regarded as money—in fact, it was more than money because it could show respect and seal agreements. Wampum is a prime example of how different cultures learned to communicate through a material culture form. In fact, it was Massachusetts's first legal currency in 1650! |

Wampum Belt | Iroquois, Northeast | Circa 1915

Wampum Belt | Maine | Circa 1914

|

Snapshots

|

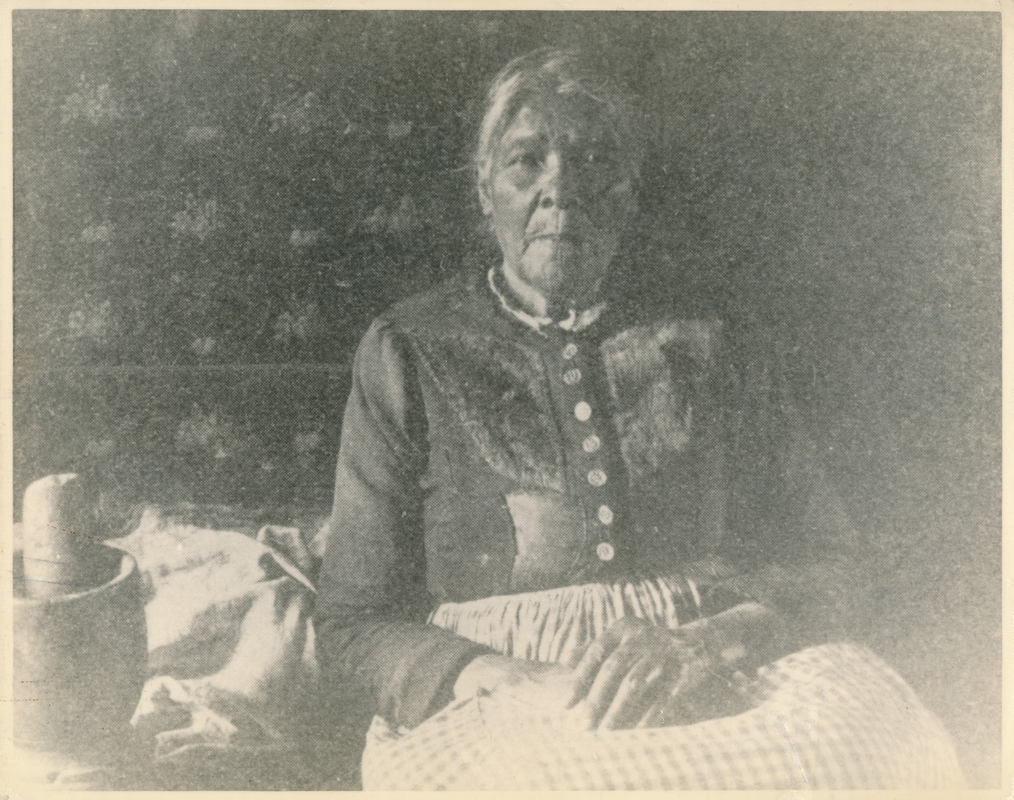

Note the mortar and pestle beside “Aunt” Mary Ann Cuffee. For many years, Mary was employed as a well-known cook at the Rogers Boarding House in Sagaponack. She passed away at the age of 95 in 1923.

The name “Lee” became a family Shinnecock one when James Lee, an African-American, married Roxanna Bunn, who was Shinnecock. This photo shows Emma Jane Lee.

|

Autumn Rose Miskweminanocsqua (Raspberry Star Woman) Williams was the first ever Shinnecock to be named Miss Native American USA in 2017.

This c. 1900 photo dshows John Henry Thompson, a Shinnecock man standing in front of an 'Indian cellar' made by digging 4-5 foot holes and roofing them with thatch. Early colonists used to complain these deserted holes were a menace to their cattle.

|

A Shinnecock Couple: Henry Cuffee and his wife, circa 1890.

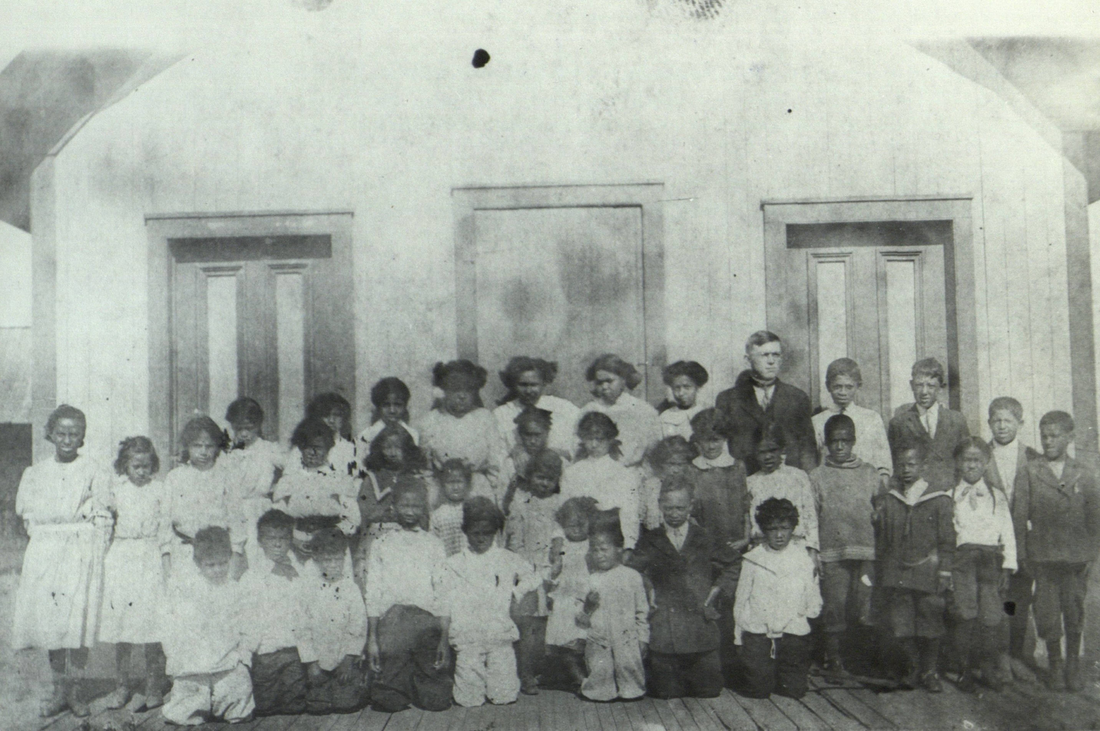

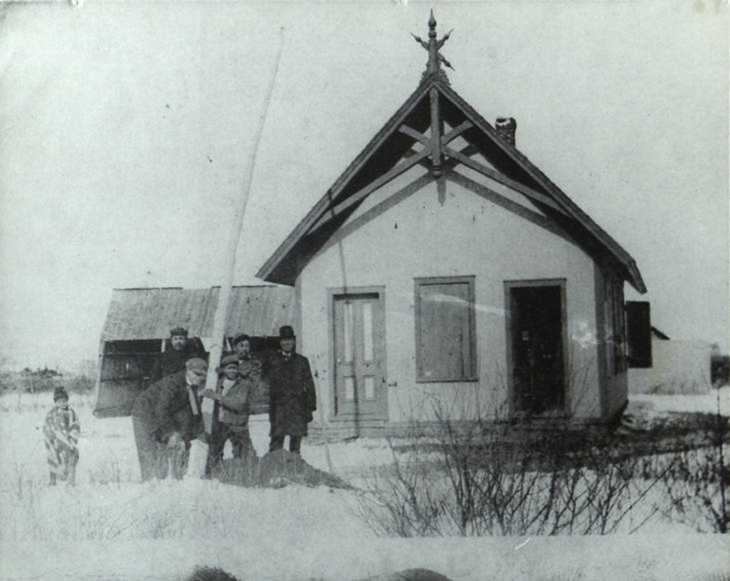

Old Shinnecock School

Located on the Shinnecock reservation.

|

Original caption reads:

“The State of New York erected a school for the Shinnecock Indians in the year of 1825. Its teachers were furnished by the State Education Department. Back in the 1830’s the school had only one classroom and one teacher. In the year of 1875, the old schoolhouse burnt to the ground and the members of the tribe raised money to see that another one was erected. Mrs. Rebecca Bunn (Aunt Becky) taught at this time, and many of the Shinnecocks still remember the days that they spent in this school with genuine nostalgia. Among those who have taught at this old school were Mr. Thomas A. Williams, a Negro who married Rose Kellis of the tribe, and Mrs. Lois Marie Hunter (Princess Nowedonah) the tribal historian. The photo has rare value indeed because it portrays the various physical types that various members of the tribe exhibited around the turn of the century.” |

Original caption reads:

“It appears to have been a bleak and wintry day when these Shinnecocks were trying to wright a flagpole that the wintry wind had blown over some years ago. The man with the mustache on the right and black shock of hair is Charles Bunn who is shown in photo 25. I would judge that this photo was taken somewhere around 1908. Pictured on the left is a shed that might have been a shelter for the horse and buggy that belonged to the teacher. Many of the members of the tribe recall the days that they and their grandparents learned the three R’s in this quaint little schoolhouse that burnt down in the year of 1967.” |