The Shinnecock & Offshore Whaling

Whaling expanded to the deep sea—and the Shinnecock followed.

|

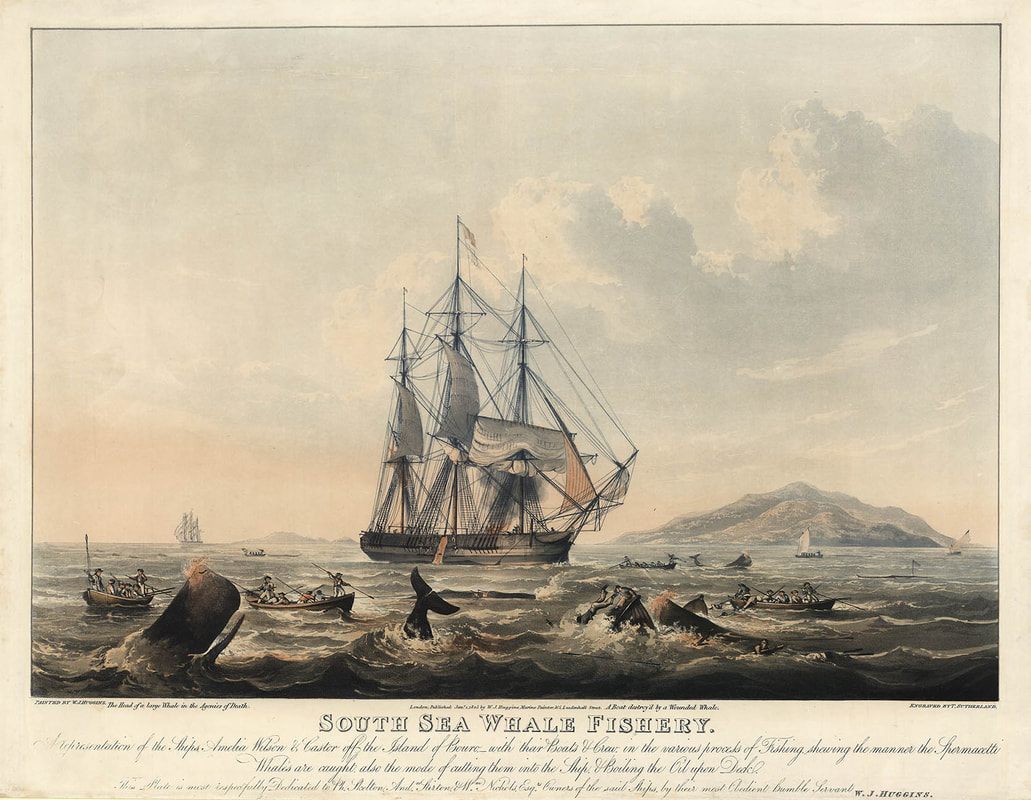

When whales near the coast became depleted, whaling crews headed to the North Atlantic, then the South Atlantic, and in the 1790s ventured around Cape Horn to whale in the Pacific Ocean.

Concurrent with its global expansion, the American whaling industry developed into a mega-capitalist endeavor run by wealthy, stay-at-home investors whose large ships and barks carried twenty to forty men as crew for hunting whales on the deep sea. Although Massachusetts came to dominate the industry in the nineteenth century, Long Island was well-represented in the world’s oceans. As their ancestors had done, Native men from Long Island continued to work as whalemen, no longer from the Long Island shore but instead on three-four year voyages that took them halfway around the world and back. Dr. Nancy Shoemaker, Historian |

|

“My great great grandfather, the whaler David Waukus Bunn, was very cultured—never cursed—and was also a great artist in whale bone and ivory.

He carved scrimshaw during his voyages, on which he sailed as first mate. He may also have created ship models since we have a photograph of him seated next to one. He carved the head of an ebony cane for his wife and brought back pieces of ivory from his voyages." - David Martine, Shinnecock Member |

Clues in Crew Lists

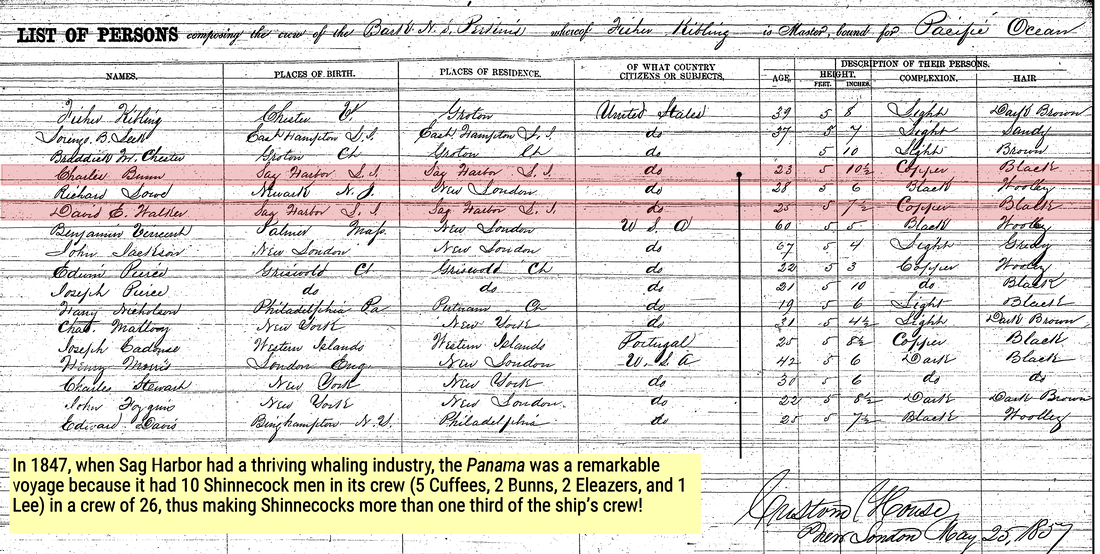

The men of many Shinnecock families participated in the whaling industry, including the Lees, Cuffees, Kellises, Walkers, Bunns, and others.

Below is a list of crew members who sailed on the Nathaniel S. Perkins from New London, CT in 1857, including Shinnecock whalers Charles Bunn and David Walker. At the time, New London was the third-largest whaling port in the country, and many Shinnecock whalers sought employment there after getting their start on Long Island ships.

Below is a list of crew members who sailed on the Nathaniel S. Perkins from New London, CT in 1857, including Shinnecock whalers Charles Bunn and David Walker. At the time, New London was the third-largest whaling port in the country, and many Shinnecock whalers sought employment there after getting their start on Long Island ships.

Courtesy Mystic Seaport Museum

Courtesy Mystic Seaport Museum

Rising Through the Ranks

The Shinnecock, along with other Native Americans in the whaling industry in the 1840s and later, rose in the ranks to become third, second, and even first mates. They exhibited a commitment to whaling as a profession and the skills required of those in command: literacy, the ability to make complex navigational calculations, and crew management. They were rewarded for their professionalism with positions of authority, which meant also a higher rate of pay, enough to secure a comfortable living.

|

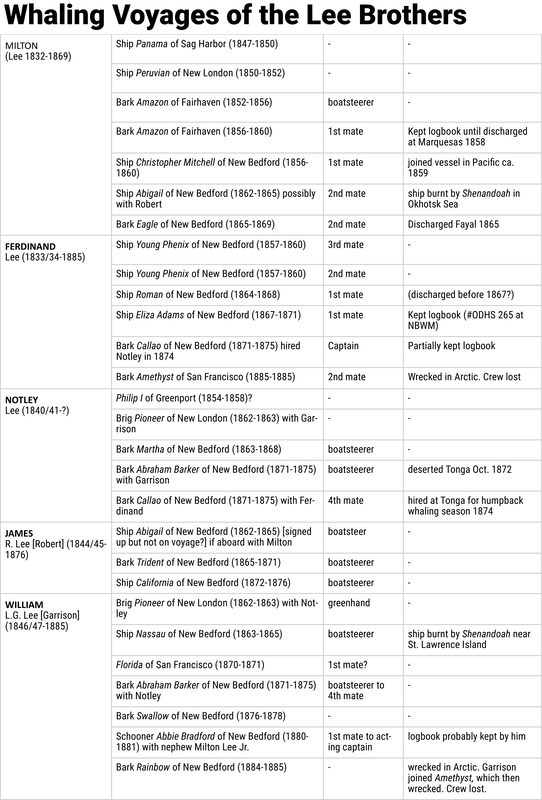

Nothing shows this better than the success achieved by members of the Shinnecock Lee family.

Even though the concentration of so much whaling talent in one family was exceptional, the Lee brothers’ experiences reveal much about the significance of whaling in the economy and culture of the Shinnecock Indian community. The Lees’ reputation as superior whalemen rested primarily on Milton, Ferdinand, and Garrison, who all attained positions of high rank. Milton and Garrison rose to be first mates on New Bedford whaleships. Ferdinand made it even further, to captain. Native American captains were a rarity in the whaling industry. Being hired as first mate, but especially as captain, was not easy for a Native American, and the Lees faced many challenges. As a job, whaling was extraordinarily taxing. But whaling was tedious, dangerous, and smelly work, and the lay system of payment—based on shares, not on wages—made it high risk, allowing for a windfall reward one voyage and a total loss the next. Surviving logbooks from the Lee brothers’ voyages, including several kept by the Lees themselves while first mates, reveal something of their lives at sea and the kinds of difficulties they dealt with as whalemen. Dr. Nancy Shoemaker, Historian

|

The Shinnecock, along with other Native Americans, generally thrived in the whaling industry—but only up to a point. Many became officers, but few became captains or investors. Less than five native men reached whaling master.

The Circassian Shipwreck

A devastating tragedy to the Shinnecock, whose effects were felt for years in the community.

In December 1876, the freight ship Circassian wrecked off the coast of Bridgehampton. The 16-man crew was taken off safely as the storm subsided. A group of Shinnecock men were then hired to retrieve the cargo. The Shinnecock rowed out to the stranded ship, proceeded to load cargo into small boats, and waited there for the next small boat.

In the middle of this operation, a new ice storm brewed. Rather than have the men brought in immediately, they were left to make one more load of cargo. Unfortunately, the ship dramatically broke apart and the men were cast into the freezing water. The ten Shinnecock men were among the thirty-two who perished.

More than half of the Shinnecock men were veteran whalers who likely sensed the destructive nature of the storm. Some Shinnecock tribal members maintain that the men were threatened and forced to complete off-loading materials even with the approaching storm. Only one Shinnecock man got off the ship in time.

The loss of these men among the 175 people on the reservation was a demoralizing blow. The Circassian widows and the twenty-five children from their families struggled to support themselves.

In the middle of this operation, a new ice storm brewed. Rather than have the men brought in immediately, they were left to make one more load of cargo. Unfortunately, the ship dramatically broke apart and the men were cast into the freezing water. The ten Shinnecock men were among the thirty-two who perished.

More than half of the Shinnecock men were veteran whalers who likely sensed the destructive nature of the storm. Some Shinnecock tribal members maintain that the men were threatened and forced to complete off-loading materials even with the approaching storm. Only one Shinnecock man got off the ship in time.

The loss of these men among the 175 people on the reservation was a demoralizing blow. The Circassian widows and the twenty-five children from their families struggled to support themselves.

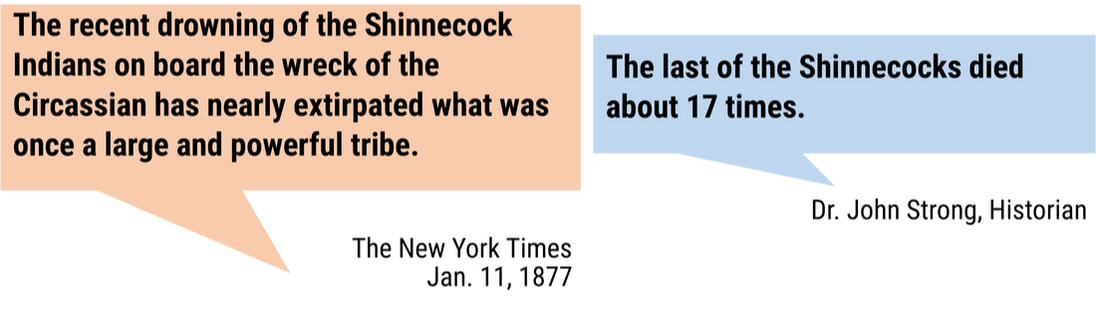

News accounts at the time incorrectly marked the “end of the tribe”: