Spotlights

Artor

|

An Early Whaler Who Challenged the System

Artor was born a short time after the first English settlers arrived on eastern Long Island. His name appears on 8 documents over a 30-year period from 1671-1703. His trail offers a unique insight into the economic opportunities and financial struggles that Shinnecock whalers faced. We first hear of Artor when he was recruited as a whaler by John Cooper in 1671, eight months before the whaling seasons started. By that fall, Artor walked away from his agreement with Cooper to set up his own independent whaling company with Papasaquin (a Montauk), and fifteen Indians. It is unknown how long this company was in operation, but there was little chance for an independent Indian whaling operation to prevail in a system where the English owned the boats, the equipment, the trying stations, the warehouses, and controlled all access to the global market. By next Spring, six of the Shinnecocks signed on with English companies. Artor continued his whaling career with several English whaling company owners, and unfortunately became ensnared in debt. The last time the name Artor appears in records is in 1703, when he was called in with 20 other Shinnecock men to confirm the sale of ancestral lands to the settlers. |

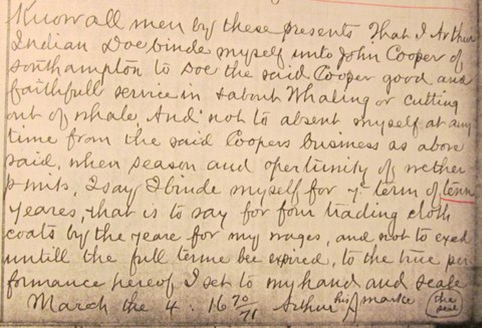

Artor’s First Whaling Contract

Know all men by these presence that I, Artor Indian, do bind myself into John Cooper of Southampton to do the said Cooper good and faithful service in & about Whaling or Cutting out of whale, and not to absent myself at any time from the said Cooper’s business as above said, when season and opportunity of either permits, I say I bind myself for the term of ten years, that is to say for four trading cloth coats by the year for my wages, and not to exceed until the full term be expired, to the true performance hereof I set to my hand and seal March the 4th, 1670 |

Artor’s experiences document the exploitive aspects of whaling.

In 1679, Artor found himself burdened with considerable debt incurred either for goods he had taken on credit or for fines imposed by the owners. The document below sounds similar to a bond servant indenture:

I Artor Indian belonging to the Shinnecock within the town of Southampton on Long Island, being indebted to Joseph Fordham of Southampton a considerable sum of money upon the [illegible] whaling expended by him. I not knowing how to make satisfaction for the said debt, do voluntarily of my own accord engage and promise to go to sea a whaling for the said Fordham, from time to time and year to year, attending all opportunities every whale season of going to sea, for the procuring of whales or other great fish…until I have fully satisfied and paid the said debt

Artor’s words express both frustration and resignation. The vague wording of Artor’s debt did not likely work to his favor.

It appears Artor took three whaling seasons (three years) to pay his debt.

In 1679, Artor found himself burdened with considerable debt incurred either for goods he had taken on credit or for fines imposed by the owners. The document below sounds similar to a bond servant indenture:

I Artor Indian belonging to the Shinnecock within the town of Southampton on Long Island, being indebted to Joseph Fordham of Southampton a considerable sum of money upon the [illegible] whaling expended by him. I not knowing how to make satisfaction for the said debt, do voluntarily of my own accord engage and promise to go to sea a whaling for the said Fordham, from time to time and year to year, attending all opportunities every whale season of going to sea, for the procuring of whales or other great fish…until I have fully satisfied and paid the said debt

Artor’s words express both frustration and resignation. The vague wording of Artor’s debt did not likely work to his favor.

It appears Artor took three whaling seasons (three years) to pay his debt.

Wickham Cuffee

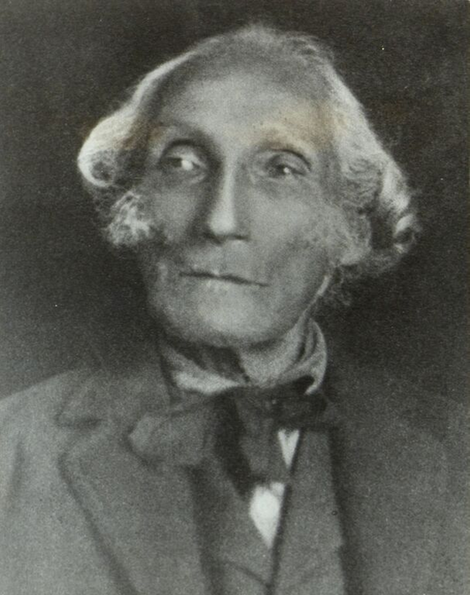

A Whaler & Craftsman Proud of His Heritage

One of nine children, Wickham Cuffee born in 1826—in a house, not a wigwam. During his career as a whaler, he was nicknamed “Eagle Eye” for his ability to spot whales at a great distance.

Wickham was a craftsman and produced scrub brushes (for sweeping and cleaning) and baskets. He was well versed in the traditions of his people and his memories of earlier Shinnecock life were of much value to ethnologists and historians.

In the lower left image, taken shortly before his death in 1915, he is shown sitting on the left. Standing next to him is his wife, Ellen Killis Cuffee, and seated is Fanny Bunn. A notable number of Shinnecock people can trace their lineage to the Cuffee, Killis, and Bunn families.

One of nine children, Wickham Cuffee born in 1826—in a house, not a wigwam. During his career as a whaler, he was nicknamed “Eagle Eye” for his ability to spot whales at a great distance.

Wickham was a craftsman and produced scrub brushes (for sweeping and cleaning) and baskets. He was well versed in the traditions of his people and his memories of earlier Shinnecock life were of much value to ethnologists and historians.

In the lower left image, taken shortly before his death in 1915, he is shown sitting on the left. Standing next to him is his wife, Ellen Killis Cuffee, and seated is Fanny Bunn. A notable number of Shinnecock people can trace their lineage to the Cuffee, Killis, and Bunn families.

Charles S. Bunn

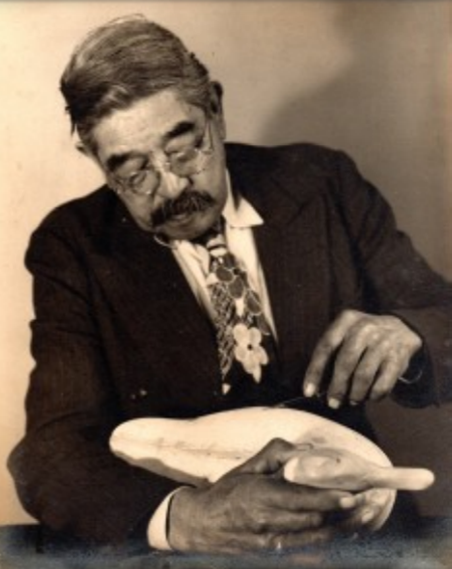

Hunter, Guide, Craftsman, Storyteller

Charles Sunmer Bunn (1865-1952) was regarded as the “best known guide among the Shinnecock” and “one of the finest hunters.” He was a graduate of what would later be renamed SUNY New Paltz, and his home at the time was one of the largest on the Shinnecock reservation. Sportsmen hired his services for hunting marsh fowl.

Charles was a great decoy carver of shorebirds, which are tools of wildfowl hunters and today regarded as prized folk art.

He shared many recollections about his own father, David Waukus Bunn, a whaler who sailed on the Lagoda and the Northern Lights. David was one of the Shinnecock men who perished in the wreck of the Circassian in 1876.

“It was no uncommon sight even during his declining years to see Charles Bunn tramping along the edge of the bay that he loved.”

See examples of his decoys on display at the Shelburne Museum: REDISCOVERING CHARLES SUMNER BUNN'S SHOREBIRD DECOYS

Charles Sunmer Bunn (1865-1952) was regarded as the “best known guide among the Shinnecock” and “one of the finest hunters.” He was a graduate of what would later be renamed SUNY New Paltz, and his home at the time was one of the largest on the Shinnecock reservation. Sportsmen hired his services for hunting marsh fowl.

Charles was a great decoy carver of shorebirds, which are tools of wildfowl hunters and today regarded as prized folk art.

He shared many recollections about his own father, David Waukus Bunn, a whaler who sailed on the Lagoda and the Northern Lights. David was one of the Shinnecock men who perished in the wreck of the Circassian in 1876.

“It was no uncommon sight even during his declining years to see Charles Bunn tramping along the edge of the bay that he loved.”

See examples of his decoys on display at the Shelburne Museum: REDISCOVERING CHARLES SUMNER BUNN'S SHOREBIRD DECOYS

Mary Rebecca Bunn Lee

|

A Public Face & First School Teacher

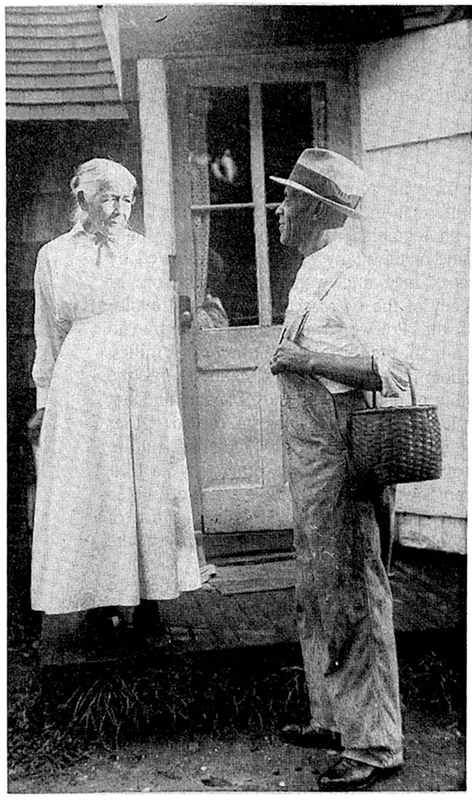

Mary was regarded as the most “publicly known Shinnecock of the 20th century.” Known as Aunt Becky, she was born around 1835 on the Shinnecock reservation, and was the daughter of David Bunn, a whaler. Both her father and brother were killed in the Circassian disaster. Mary attended New Paltz College and married Milton Lee. She worked for the families of both President Theodore Roosevelt and the Thompson family of Gardiner lineage. She was the first Shinnecock tribal member to teach at the old Shinnecock School. Below, Mary is seen at her home with a visitor in 1933, standing on a porched house financed by whaling voyages. Mary recalled that her grandmother lived in a wigwam. |

Jean Arch

|

A ‘Lovable Lady’ With a Welcoming Home

Jean Arch, born Stella Virginia Arch in 1872, was known as being very kind and always willing to do a favor for people. When Indians from other tribes used to find housing difficult to obtain during the weekend of the Shinnecock Pow Wow, they would be referred to the home of Aunt Jean, who wouldn’t turn people away from her cozy home if she had space. During Christmas, her living room would be loaded with boxes and baskets of gifts brought to her from far and near. She was known for her cooking, including a stew she called “Long Island Hurry,” which wives of whalers would whip up quickly when a ship anchored. With her independent spirit, she rode her bicycle daily from the reservation to Southampton daily until her seventies. She passed away in 1969. |

Edna Walker Eleazar

|

A Matriarch of Shinnecock & Montauk

“Miss Edna” or “Cousin Edna” was one of the most recognized figures on the reservation for some time. Edna’s mother was a Shinnecock, and her father was a Montauk. She recalled as a ten-year-old girl her mother answering a knock on the door one day announcing that both her father, Moses Walker, and uncle had perished in the Circassian wreck. Edna worked at the Southampton Library into her old age, either walking to work or catching a ride from other tribal members. Edna passed away after her 100th birthday in 1969. |

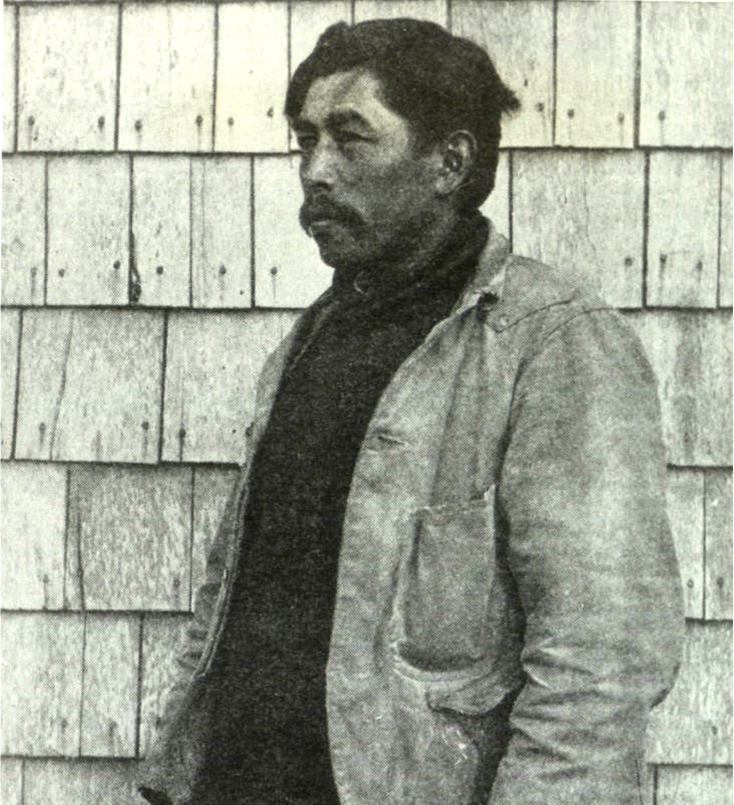

Shane Weeks

Singer, Dancer, Artist

|

Where were you raised?

My family resides on the Shinnecock reservation in Southampton where I was raised. What is your relationship with water and the ocean? I have grown up hunting and fishing on our waters my entire life. It has become an everyday part of my life. How does your heritage influence the way you see water? My Shinnecock heritage lends a unique view to how I see the waters and the resources they provide. When I look at the waters of our traditional Shinnecock homelands I think of all of the life it has provided our people for generations. From harvesting whales as a food source to transporting our 80 man canoes across the sea. I see the direct interconnection between us and it and its relationship to the fate of generations to come. Did you have to overcome any obstacles to work in your field? One of the major obstacles I have had to overcome has been breaking through the wall off oppression that drove our traditional ways far underground. It has only been since the 1970's that our traditional ways were legally allowed in the U.S. I have had to search, ask, and travel far and wide to find out what I know today. What are your biggest concerns with respect to your community today? One of my biggest concerns today of my community and the population in general is a lack of understanding the importance our traditional knowledge lends to the worldly balance and survival of our people and humanity as a whole. What projects are you working on now? As of now I am currently working on several projects to perpetuate our knowledge including films, books, and international indigenous cultural exchanges. What do you find non-native people are surprised to learn about the Shinnecock? One of the biggest facts that surprise many people is the fact that we are still here and that we still maintain our traditional territories in one of the wealthiest places in the world. |

|

"The Shores of Shinnecock: This is Who We Are."

|

"The Shores of Shinnecock: The Road Home."

|

Shinnecock Women in Early Photography

|

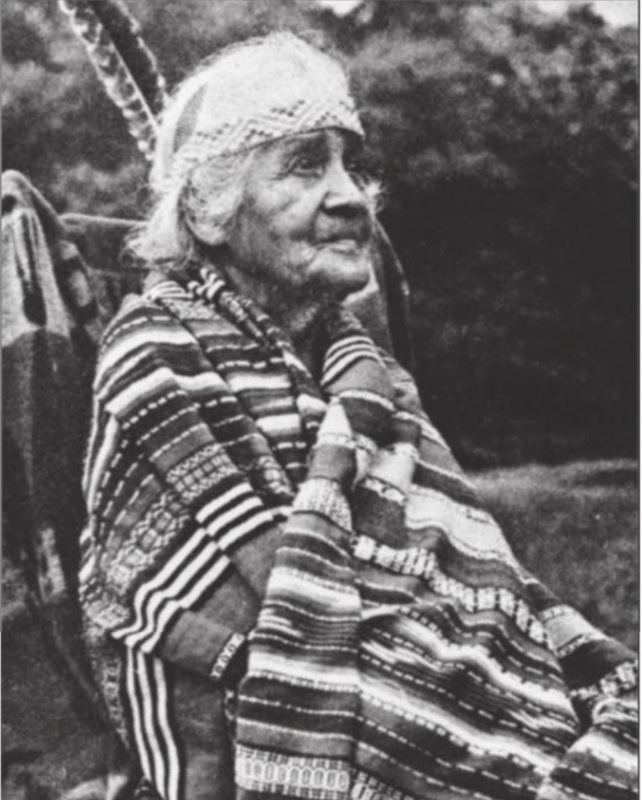

This is the oldest known photo of a Shinnecock person.

Mary Hugh Waukus is shown sitting. She is the mother of Cynthia Walker Bunn (shown at right). Mary lived from 1767-1867. |

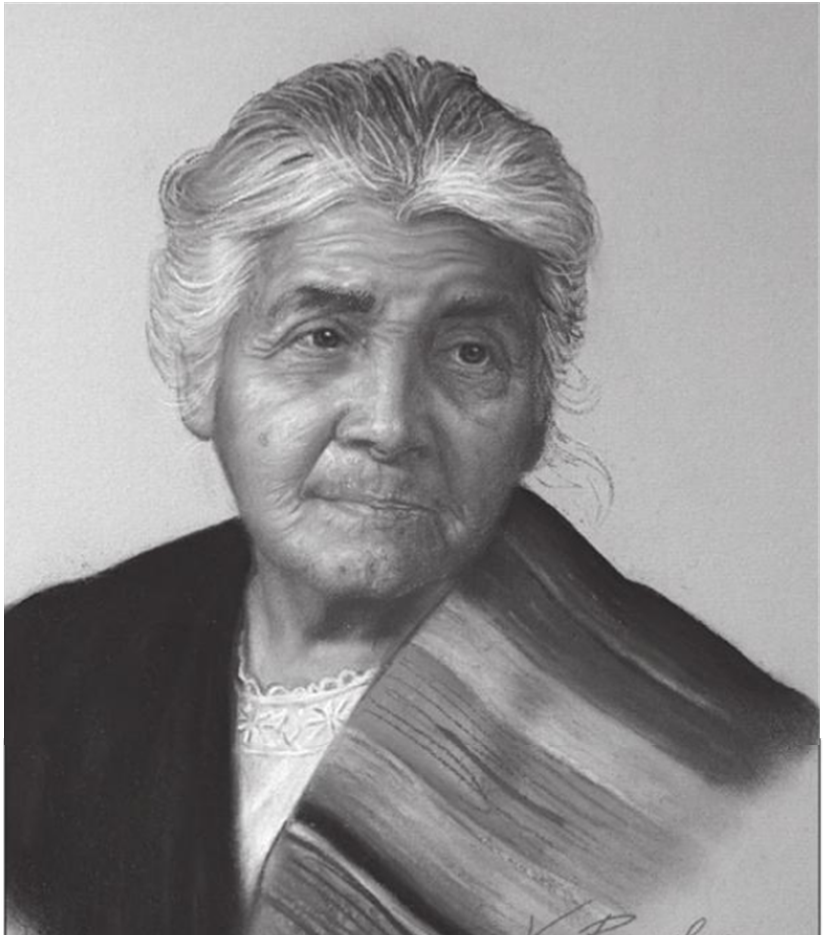

Cynthia Walker Bunn was born in 1800. Her husband was a whaler. Two of her five children died at sea, including one in the Circassian disaster. Cynthia worked as a seamstress in Southampton. Unfortunately, she died from smoke inhalation in a house fire in 1881.

|

Charity Bunn Kellis lived from 1818-1897. Kellis/Killis is a traditional Shinnecock surname. Charity lived on the shore of Kellis Pond in Bridgehampton.

|