|

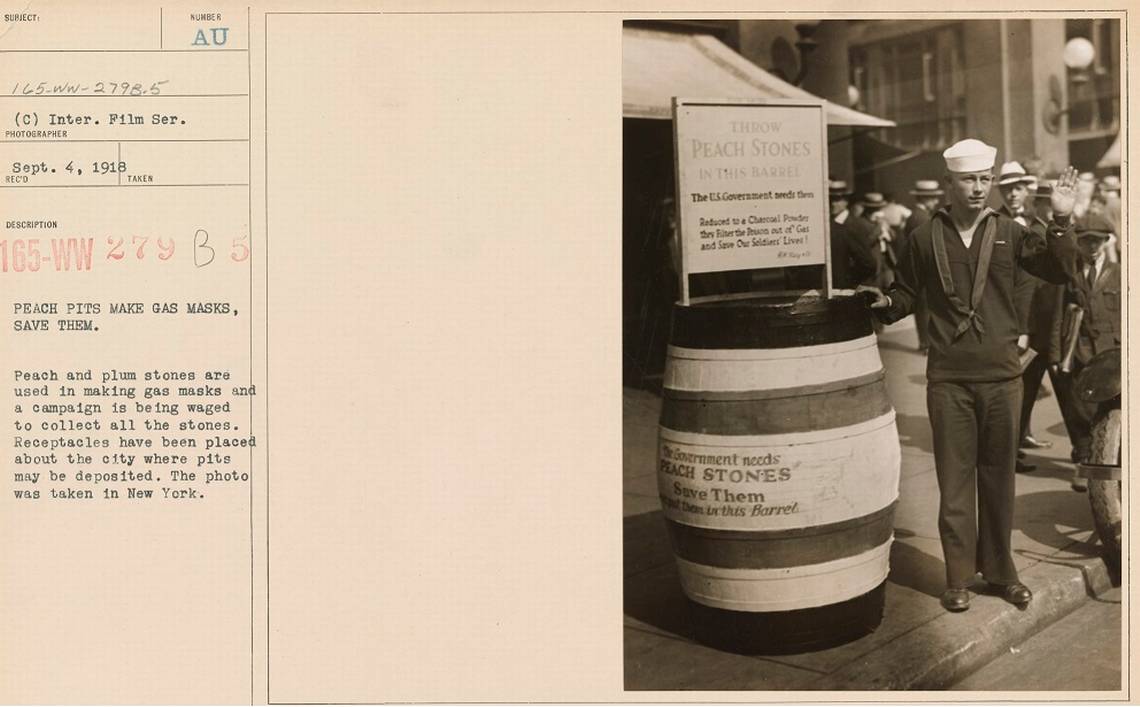

by Joan Lowenthal A 1918 call for supplies mirrors the health crisis today. The Red Cross made an urgent plea for masks for the doctors and nurses in quantities and at once. The Cold Spring Harbor branch spread the word that, “A special order for contagious ward masks has been received and the masks are being made at the Red Cross room and every evening in the Library. Members and their friends are urged to help with this work until the order is completed.” (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, October 04, 1918, Page 7) In 1918, not only was there a worldwide flu pandemic, but World War I was still being fought. Gas masks for men at the front line were desperately needed and the local Huntington Red Cross encouraged people to collect peach pits, nuts and other fruit pits also called stones and drop them into the receptacles found in several local stores. The government needed 750 tons of peach stones, plum stones, olive pits, and all hard nut shells especially coconut shells to supply charcoal for gas masks each day. The charcoal derived from these stones was forty times as strong as ordinary charcoal. Two hundred peach stones were needed for one gas mask. This was a nationwide nut-gathering campaign. (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, September 13, 1918, Page 1) By the beginning of October 1918 Huntington had done very well in saving their peach stones and other nut shells. Barrels and barrels were collected and shipped to a carbon plant where machinery ground up the bits and the material was distilled to uniform-sized carbon pieces. The powder was then shipped to the Gas Defense Plant New York located in Long Island City, NY where factory workers assembled gas masks. (Laura Corley. “How peach pits helped American allies win World War I,” The Macon Daily Telegraph, November 12, 2018.) People in the Huntington area responded so enthusiastically that it was not necessary to ask the Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls to canvas for nuts door to door. But these boys and girls were asked to pick up the peach stones in the local orchards. “There should be no peach stones left in the orchards doing no one any good, when they might save some precious life. (The Long Islander, Huntington NY , October 04, 1918, Page 2) There was an urgent appeal for nurses all over the country to replace the nurses that were sent overseas and to home military camps. The Long-Islander attempted to entice young women to become nurses. “The profession of nursing is one that should appeal to the ambition of young women fitted for the work; the pay is good and it is never overcrowded. In its higher branches it closely approaches the profession of the surgeon in its educational requirements.” The Long-Islander, Huntington, September 13, 1918.  The first wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic was fairly mild and many people recovered and the death rate was low. By the end of the summer of 1918 the second wave of the virus was virulent, highly contagious and deadly. In fact, the highest fatality rate of the pandemic was October 1918. Victims of the disease died within hours or days of developing symptoms and many were young adults. Local Long Island newspapers only mention the flu in the spring of 1918 infrequently, but by the fall especially in the month of October there are numerous accounts of local people dying and closings of churches, schools, and cancelling of events. The Jones family whose descendants started the Whaling Company in Cold Spring Harbor lost a member of their family due to the “Spanish Flu.” Philip Livingston Jones died at the Jones Manor Farm in Oyster Bay, NY. He was only 28 and left a wife and young son.(The Long Islander, November 01, 1918, Page 5). Sadly his mother Mary Elizabeth passed away the week before of a stroke at the age of 64 and his older brother Oliver Livingston Jones passed away the previous March at the age of 38. His death certificate lists bronchial pneumonia as the reason for death which were complications of the Spanish Flu. The devastating second wave of the “Spanish Flu” occurred in the US because returning soldiers infected with the flu spread it to the general population. Especially hard hit were densely populated cities. Many city governments were not ready for the onslaught. Philadelphia went ahead and had a Liberty Loan parade which was attended by tens of thousand of people. The disease spread like wildfire. In 10 days about 1,000 Philadelphians were dead and about 200,000 sick. By contrast citizens in San Francisco were fined $5 if they were caught in public without masks. The “Spanish Flu” took a toll on the economy. Even mail delivery and garbage collection was impeded and in many places there were not enough farm workers to harvest crops. Nonessential businesses were not mandated to shut down, but they were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Does history actually repeat itself? For more info check out:

5 Comments

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed