|

By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director

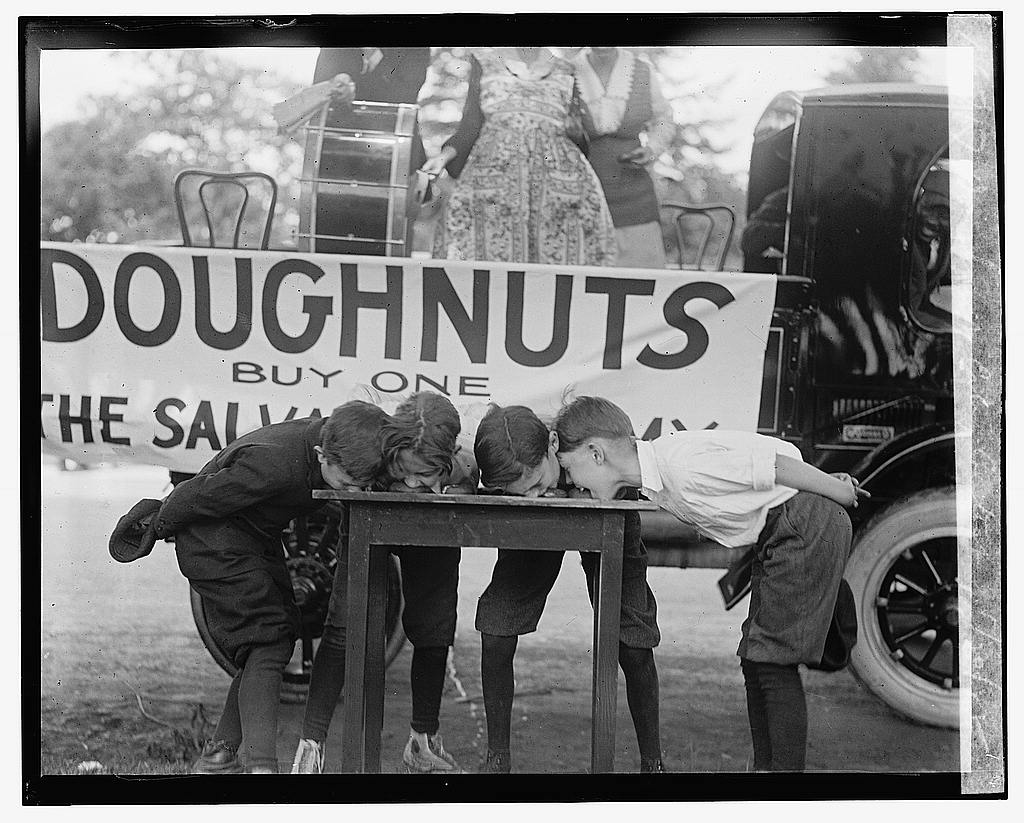

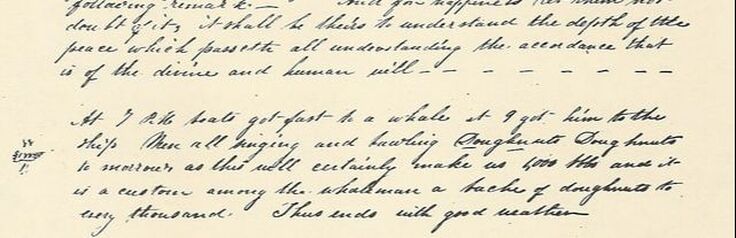

The cook would have then passed the dough on to the crew on deck, who took care of the cooking. The fritters were deep-fried in none other than whale oil in trypots - enormous, black cauldrons filled with shimmering whale oil rendered from whale blubber. The dough balls were lowered into these vats of oil, the crew watching them bob in the boiling gold before lifting them out with a skimmer. This long-handled strainer was designed to separate blubber from oil, but was perfectly suited for lifting doughnuts out as well. The crew would have wiped their dirty hands on the backsides of their pants and closed their eyes as they bit into these fresh, hot, puffy doughnuts, literally eating their bounty - a welcome change from the monotonous, paltry fare normally served on a whaleship. Several whaling wives who traveled with their husband-captains at sea recorded the serving of doughnuts. On Sunday, July 26, 1846, Mary Brewster wrote in her journal, “At 7PM boats got fast to a whale, at 9 got him to the ship. Men all singing and bawling [boiling] Doughnuts, Doughnuts tomorrow, as this will certainly make us 1000 bbls [barrels] and it is custom among the whaleman a bache [batch] of doughnuts to every thousand. Thus ends with good weather.” The next day, she noted, “This afternoon the men and frying doughnuts in the try pots and seem to be enjoying themselves merrily.” On another occasion, Henrietta Deblois stepped in to help with the cooking process. She recorded on the Merlin in 1858: “Today has been our doughnut fare, the first we have ever had. The Steward, Boy, and myself have been at work all the morning. We fried or boiled three tubs for the forecastle [sleeping area for crew] - one for the steerage. In the afternoon about one tub full for the cabin and right good were they too, not the least taste of oil – they came out of the pots perfectly dry. The skimmer was so large that they could take out a 1/2 of a peck at a time. I enjoyed it mightily." While whale oil was typically off-tasting, those who ate the donuts described only deliciousness. One exception was missionary Betsey Stockton, who sailed on a whaler to Hawaii in 1822. She wrote, “The crew [is] engaged in making oil of two black fish [whales] killed yesterday… we have had corn parched in the oil; and doughnuts fried in it. Some of the company liked it very much. I could not prevail on myself to eat it.” Keep an eye out for special offers from local donut shops in celebration of this day!

Read More:

4 Comments

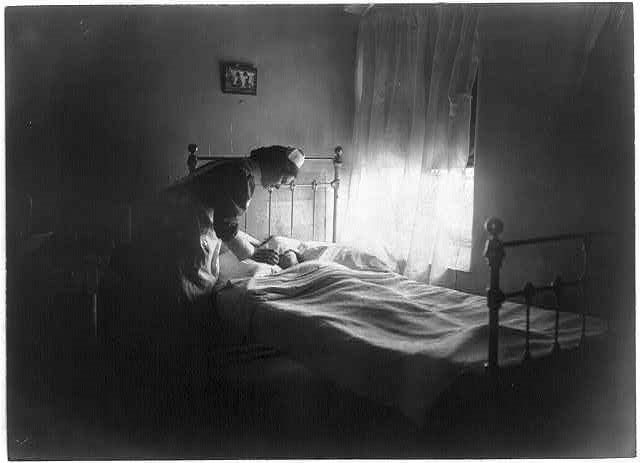

In Celebration of National Nurses Week: May 6-12, 2019By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director of The Whaling Museum of Cold Spring Harbor ***In honor of National Nurses Week, the museum is offering pay-as-you-wish admission for nurses (with current ID) and their families (up to 6 people) from Tues-Sunday, May 7-12 2019 as the museum recognizes the importance of nursing roles which whaling wives often took in the whaling industry.*** Becoming ill is never fun. Becoming ill when away from home is worse. And becoming ill at sea on a whaling ship is the worst of all. “Let a man be sick anywhere else - but on shipboard,” wrote whaler Francis A. Olmstead in 1841 in Incidents of a Whaling Voyage. Whalers who fell ill could find little comfort. Francis continued to explain, “When we are sick on shore, we obtain good medical advice, kind attention, quiet rest, and a well ventilated room. The invalid at sea can command but very few of these alleviations to his sufferings.” There were no ‘sick days’ for whalers, who were expected to work during busy times if they could stand. The incapacitated whaler would lie on his grimy, cramped straw mattress in his misery, listen to the nonstop creaking of the ship, roll from side to side with the swaying of the ship, and breathe the fishy, putrid air. He would eventually be visited by the “doctor,” a.k.a. the captain. The skipper would rely on his weak medical and surgical knowledge as he opened his medicine chest and offered some powdered rhubarb, a little buckthorn syrup, or perhaps mercurial ointment, chamomile flowers, or cobalt. The whaler would then either recover or die. If he passed, the captain would casually mention his death in the next letter home, and perhaps pick up a replacement at the next port. If the whaler was lucky, he might awaken from his burning fever and shivering chills to hear a soothing voice, feel a cool cloth being gently placed on his forehead, and perhaps taste a bit of food offered to him. He would sit up to catch a glimpse of this angel visiting him with her wide skirt and billowing sleeves.

Most wives were happy to feel valuable and help contribute to the voyage’s success. Some took the initiative to go beyond their nursing roles: Calista Stover of Maine persuaded the crew of a sailing ship to swear off tobacco and alcohol while in port (the pledge didn’t stick). Others tried to reform men’s swearing. However women tried to improve the crew, their support gives understanding to the root of the word “nurse,” which is Latin for nutrire – nourish. No wonder Charles. W. Morgan wrote, “There is more decency on board when there is a woman.” EXPLORE MORE

By Nomi Dayan Whaling was a risky business, physically and financially. Life at sea was hazardous. Fortunes were made or lost. Whalehunts were perilous, as was the processing of the whale. Injuries were rampant and death was common, sometimes on nearly every voyage. In some instances, the deceased was none other than the captain. Captain Sluman Lothrop Gray met his untimely end on a whaleship. Born in 1813, very little is known of his past, his family, or his early experiences at sea. In 1838, he married Sarah A. Frisbie of Pennsylvania in the rural town of Columbia, Connecticut. His whaling and navigational skills must have been precocious, because in 1842, in his late twenties, Gray became a whaling captain – and a highly successful one. His wife, Sarah, joined him in his achievements, living with him at sea for twenty years. Three of their eight children were born during global whaling voyages. Gray commanded a string of vessels: the Jefferson and Hannibal of New London, CT to the Indian and North Pacific Oceans, the Mercury and Newburyport of Stonington, CT to the South Atlantic, Chile, and Northwest Pacific Oceans, and Montreal of New Bedford, MA to the North Pacific Ocean. While financially successful, Gray’s crew felt his harsh personality left much to be desired. Some of his blasphemies were recorded by a cabin boy on the Hannibal in 1843. He did not hesitate to flog crew members for minor mistakes. Unsurprisingly, when Sarah reported her husband had taken ill, the crew rejoiced. (To their chagrin, he recovered.) As Gray aged, he attempted to retire from maritime living and shift into the life of a country gentleman. He bought 10 acres of land in Lebanon, Connecticut and lived there for 7 years, where his house still stands. This bucolic life did not last, and Gray returned to whaling. With his wife and three children – Katie, Sluman Jr., and Nellie aged 16, 10, and 2, he sailed out of New Bedford on June 1, 1864 on the James Maury. Built in Boston in 1825 and sold to New Bedford owners in 1845, the James Maury was a hefty ship at 394 tons. Gray steered the course towards hunting grounds in the South Pacific. Unexpectedly, after nine months at sea in March 1865, he suddenly became ill. The closest land was Guam - 400 miles away. Sarah described his sickness as an “inflammation of the bowels.” After two days, Captain Gray was dead. The first mate reported in the ship’s logbook: “Light winds and pleasant weather. At 2pm our Captain expired after an illness of two days.” He was 51 years old. Sarah had endured death five times before this, having to bury five of her children who sadly died in infancy. She could not bear to bury her husband at sea. Considering how typical grand-scale mourning was in Victorian times, a burial at sea was anything but romantic. It was not unheard of for a whaling wife to attempt to preserve her husband’s body for a home burial. But how would Sarah embalm the body? Two things aboard the whaleship helped: a barrel and alcohol. Sarah asked the ship’s cooper, or barrelmaker, to fashion a cask for the captain. He did so, and Gray was placed inside. The cask was filled with “spirits,” likely rum. The log for that day records: “Light winds from the Eastward and pleasant weather; made a cask and put the Capt. in with spirits.” The voyage continued on to the Bering Sea in the Arctic; death and a marinating body did not stop the intentions of the crew from missing out on the summer hunting season. However, there was another unexpected surprise that June: the ship was attacked by the feared and ruthless confederate raider Shenandoah, which prowled the ocean burning Union vessels, especially whalers (with crews taken as prisoners). The captain, James Waddell, had not heard – or refused to believe - that the South had already surrendered. When the first mate of the Shenandoah Lieutenant Chew came aboard the James Maury, he found Sarah panic-stricken. The James Maury was spared because of the presence of her and her children – and presumably the presence of her barreled husband. Waddell assured her that the “men of the South did not make war on women and children.” Instead, he considered them prisoners and ransomed the ship. 222 other Union prisoners were dumped onboard the ship and sent to Honolulu. One can imagine how cramped this voyage was since whaleships were known for anything but free space. A year after the captain’s death, the remaining Gray family made it home in March 1866. The preserved captain himself was shipped home from New Bedford for $11. Captain Gray was finally buried in Liberty Hill Cemetery in Connecticut. His resting place has a tall marker with an anchor and two inscriptions: “My Husband” and “Captain S. L. Gray died on board ship James Maury near the island of Guam, March 24, 1865.” Sarah died twenty years later, and was buried next to her husband. It is unknown if Gray was buried “as is” or in a casket. There are no records of Sarah purchasing a coffin. Legend has it that he was buried barrel and all. Nomi Dayan is the Executive Director at The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor, NY. Read More:

Turn of the century glass plate portrait of mother and infant in Australia. Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Turn of the century glass plate portrait of mother and infant in Australia. Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. By Nomi Dayan As I prepare to become a mother for the third time around, I am brought to reflect on one of the most dirty, reeking, and unlikely places to possible to birth a baby: a whaleship. Today’s challenges with pregnancy and childbirth pale in comparison with the experience of the 19th century woman – and even more so, the challenge whaling wives faced at sea. Because whaling wives saw so very little of their husbands, some resorted to going out to sea – a privilege reserved for the wife of the captain. Aside from dealing with cramped and filthy conditions, poor diets, isolation, and sickness, many wives eventually found themselves – or even started out - “in circumstance.” In the 19th century, pregnancy was never mentioned outright. Even in their private diaries, whaling wives rarely hinted to their pregnancies. Some miserably record an increase in seasickness. Only the very bold dared to delicately remark on the creation of pregnancy clothes. Adra Ashely of the Reindeer wrote to a friend in 1860, “I am spending most of my time mending – I want to say what it was, but how can I! How dare I!” Martha Brown of Orient was more forward by mentioning in her diary in 1848 that she is “fixing an old dress into a loose dress,” with “loose” meaning “maternity.” Once the time of birth approached, women at sea faced two options: to be left on land – often while the crew continued on - or to give birth on board. Giving birth on land was far preferable, as the mother would be theoretically closer to medical care and whatever social support was available. Martha Brown was left in Honolulu – much to her personal dismay to see her husband depart for 7 months – but fell into a supportive society of women, most left themselves in similar situations. During Martha’s “confinement” after birth when she was restricted to bedrest, a fellow whaling wife nursed her. When Captain Brown returned, he wrote to his brother: “Oahu. I arrived here and to my joy found my wife enjoying excellent health with as pretty a little son as eyes need to look upon. A perfect image of his father of course – blue eyes and light hair, prominent forehead and filled with expression.” Giving birth on land did not always ensure a hygienic setting as one would hope. Abbie Dexter Hicks of Westport accompanied her husband Edward on the Mermaid, sailing out in 1873. Her diary entry on the Seychelle Islands was: “Baby born about 12 – caught two rats.” Some whaleships found reaching a port before birth tricky. In 1874, Thomas Wilson’s wife Rhoda of the James Arnold of New Bedford was about to give birth, but when the ship arrived at the Bay of Islands of New Zealand, there was no doctor in town. A separate boat was sent to search up the Kawakawa River for 14 miles; when a doctor was finally found and retrieved, the captain informed the doctor that it was a girl. Some babies were born aboard whaleships – either by design or by accident, despite hardly ideal conditions. Births, if were recorded in the ship’s logbook, were mentioned matter-of-factly. Charles Robbins of the Thomas Pope was recorded in April 1862: “Looking for whales… reduced sail to double reef topsails at 9pm. Mrs. Robbins gave birth of a Daughter and doing nicely. Latter part fresh breezes and squally. At 11am took in the mainsail.” Captain Charles Nicholls was in for a surprise when he headed to New Zealand on the Sea Gull in 1853 with his wife. Before the birth, fellow Captain Peter Smith had told him during a gam (social visit at sea), “Tis easy,” and advised the first mate be ready to take over holding the baby once it was born. When the time came, Captain Nicholls dutifully handed the baby to the first mate, only to return several minutes later shouting, “My God! Get the second mate, fast!” – upon when he promptly handed out a second infant. Captain Parker Hempstead Smith’s wife went into labor unexpectedly: “Last night we had an addition to our ship’s company,” seaman John States recorded on February 18, 1846 on board the Nantasket of New London, “for at 9pm, Mrs. Smith was safely delivered of a fine boy whose weight is eight lbs. This is quite a rare thing at sea, but fortunately no accident happened. Had anything occurred, there would have been no remedy and we should have had to deplore the loss of a fine good hearted woman.” He also added his good wishes for the baby: “Success to him – may he live to be a good whaleman – though that would make him a great rascal.” The author is the Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ More Reading: Druett, Joan. Petticoat Whalers. Auckland: Collins, 1991 MacKay, Anne ed. She Went a Whaling: The Nournal of Martha Smith Brewer Brown. Oysterponds Historical Society, 1993  Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor joined her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. Courtesy Audrey Hank Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor joined her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. Courtesy Audrey Hank Recalling The Woman’s Experience on Whaleships In Honor of Women’s History Month By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center, Cold Spring Harbor “It is no place for a woman,” wrote Captain James Haviland on the Baltic in 1856, “on board of a whaleship.” The long saga of hunting whales, one of Long Island’s most historically prominent industries, was unquestionably viewed as man’s world. Whalers were exclusively male, and their lives were fraught with dangers and hardships, cramped and filthy living conditions, rowdy company, monotonous life, and risky circumstances. No wonder Irish traveler John Ross Browne wrote in 1846, “There is no class of men in the world who are so unfairly dealt with, so oppressed, so degraded, as the seamen who man the vessels engaged in the American whale fishery.” These conditions did not extend into the prescribed separate domestic sphere of “the fair sex.” The 19th century saw sharp gender roles for men and women, and Ladies were supposed to be pious, graceful, passive, pure, and focused on children and homemaking. The male-dominated industry relied on family members to manage life ashore during their long absences, which could extend three to four years. Women who remained home suddenly found themselves as lone masters of their households. They maintained their families as single parents, took care of elderly parents, paid the bills (or lived on credit), tended to any farming, and waited with wifely devotion. To help make money during their husbands’ absence, some women became entrepreneurs, running inns, becoming teachers, or serving as midwives. Women also formed deep relationships within their own female society, using a network of communal support to fill the void created by their temporary abandonment. The life of a whaling wife was undoubtedly a lonely one, almost like that of a widow. She would ache for the day her husband would retire. But as time went on, some women found themselves incapable of enduring the separation anymore, and a number of captain’s wives broke boundaries by deciding to do what no woman had done before: join their husbands at sea. One can understand their impetus when looking at Azubah Cash of Nantucket. She had been with her husband for half a year out of 11-year marriage, spurring her to sail with him on his next voyage. More often than not, these wives were not renegades and rebels. They simply preferred the discomforts of life at sea to years of separation at home, defying convention which placed the woman’s role in the home, and became trailblazers by necessity. In the early 19th century, whaling wives were rare, as such behavior was unladylike. But as the industry boomed in numbers – and voyages grew in length of years - an increasing number of women made the decision to endure long and difficult years at sea, either with or without their children, showing remarkable endurance and courage. By the 1850’s, one out of six whaleships carried the captain’s wife aboard. These vessels were nicknamed “hen frigates.” A whaling wife on board would still spend her time waiting - not for her husband’s return, but instead for the ship to fill up with oil. She would not take part in the whaling process, other than casually spotting a whale; instead she would fill her days educating her children, reading, washing clothes, sewing, writing in her diary, and cross-stitching while confined in cramped quarters to pass the long hours. While a separate cook was hired to oversee meals for the crew, she may have prepared special treats. Some wives learned how to navigate, including Maria Cartwright Baldwin of Shelter Island, who learned to take the helm. Others made efforts to bring religion to the crew. The crew were commonly pleased to have a woman aboard. Wives often served as nurses, a valuable role in a place where sickness and injury, some severe, were common. Women also had a calming effect on the seagoing male society; their presence made it more likely holidays would be observed, and if the captain punished a crew member, he might do so less harshly. Children could be also be a welcome distraction from the flat monotony of life at sea. However, there were instances where crew members did show frustration and resentment when family life inevitably disturbed what financially mattered – catching as many whales as possible in the shortest amount of time possible. Once whaling wives were socially accepted, captains often celebrated their companionship and closeness. Captain Henry Gardiner of Quogue missed his wife Polly so much that he often doodled her name in the margins of the ship’s logbook, or daily record. She joined him on the next voyage, where she cross-stitched a sampler which is currently on view at the Whaling Museum in Cold Spring Harbor, which she dated, “Bound to the Pacific Ocean in the ship Dawn. March 16, 1828.” Whaling wives’ diaries are powerful testaments to the hardships they endured, including illness, boredom, violent seasickness, powerful storms, dangerous whaling grounds, frightening mutinies, and death. Conditions at sea left much to be desired, with rampant fleas, roaches, and rodents. Sarah Eliza Jennings of Sag Harbor was aboard the Mary Gardiner which was chased by a Confederate raider, a frightening ordeal, and Elizabeth White of Cold Spring Harbor was aboard the Courser when it was rammed by a steamship and sunk off the coast of Chile in 1873. Several Long Island whaleships were caught in an early Arctic freeze in 1871, and wives and their children escaped onto the ice with the crew (all were rescued). Whaling wives’ diaries also reflect the excitement of the rare chance to socialize with women who happened to be passing by on other whaleships, an experience called gamming. The opportunity was a chance to catch up on news and fill the tremendous void of social contact. Even with their husbands at sea, seagoing wives - known for their propriety - faced social isolation as the only woman on board. When seagoing wife Eliza William’s brother in law was asked what her success at sea could be attributed to, he replied “always minding her own business.” When wives found themselves “in circumstance,” they were often conveniently deposited in Hawaii for several months while the crew continued on. Interestingly, a society of whaling wives grew there, forming a social network and domestic circle. They helped each other with births, circulated crochet patterns, and shared each other’s company. Martha S. Brewer Brown (1821-1911) of Oysterponds spent time in Hawaii. After the agonizing choice to leave her two-year-old daughter with relatives, she sailed with her husband, Edwin Peter Brown, who was one of Long Island’s most successful whaling captains of all time: on one voyage, he filled his ship with 1,500 barrels of oil in 363 days, circling the globe without dropping anchor and setting a world record. Martha unhappy and resentful at being left in Hawaii to give birth. “My husband left me in one of the most unpleasant situation a Lady can be left in, without her husband, among strangers, with the request that I would do my [clothes] washing myself – a thing which no other American Lady does, not even the mission Ladies,” she wrote in her diary. She forbade her husband to leave her for whaling again, but he did. Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor was another brave soul to join her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. She too lived in Hawaii for a time, becoming close friends with other women there, while the crew continued on to the Okhotsk Sea. Her letters expound on Hawaiian life at the time and are in Mystic Seaport Museum’s collection. Some mothers raised their children at sea for prolonged periods of time. Caroline Rose (the “Belle of Southampton”) sailed with her husband, Captain Jetur Rose, for 15 years. One cabin boy called the couple “the finest people he had ever met.” Caroline gave birth to her only child, Emma, in Honolulu in 1856, who was raised at sea. Emma logged thousands of miles before her 13th birthday. When a missionary came on board to try to educate Emma, claiming “no one on a whaler knew anything,” Emma stated, “I know the Ten Commandments and multiplication table, and that is enough for any little girl to know.” Mothers certainly had to deal with the ordeal of children falling sick at sea. Elizabeth Jones of Setauket on the Tri-Mountain cared for five children who came down with measles at sea, all at the same time (all the children recovered). Aside from whaling wives, other “sister sailors” joined their husbands at sea on coastal traders, such as Mary Satterly of Setauket, who spent her 24-year marriage at sea with her husband, Captain Henry Rowland, starting in 1852. Compared to other regions, whaling wives from Long Island were relatively infrequent because the wife-travelling trend was not synced with the area’s earlier decrease of local whaling companies. But even when women were not physically present on whaleships, their presence remained ubiquitous in another way. To fill idle hours at sea, whalers carefully carved scrimshaw, painstakingly etching images on whale teeth and bones. One of the most widespread themes is a fancy, beautifully dressed woman. Some pieces depict sweethearts or female relatives; others were copied out of advertisements; others were dreamy, classy, high-society fantasies conjured by men who had not seen a woman in months (as well as not having bathed in months). It is a treat today to be able to gaze at these women, who stare back at us from the surface of a tooth. Frozen in their cold medium of bone, they challenge us to rethink our own assumptions today: is there a ship would we rather be on? On View at the Museum in March:

More Reading:

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed