|

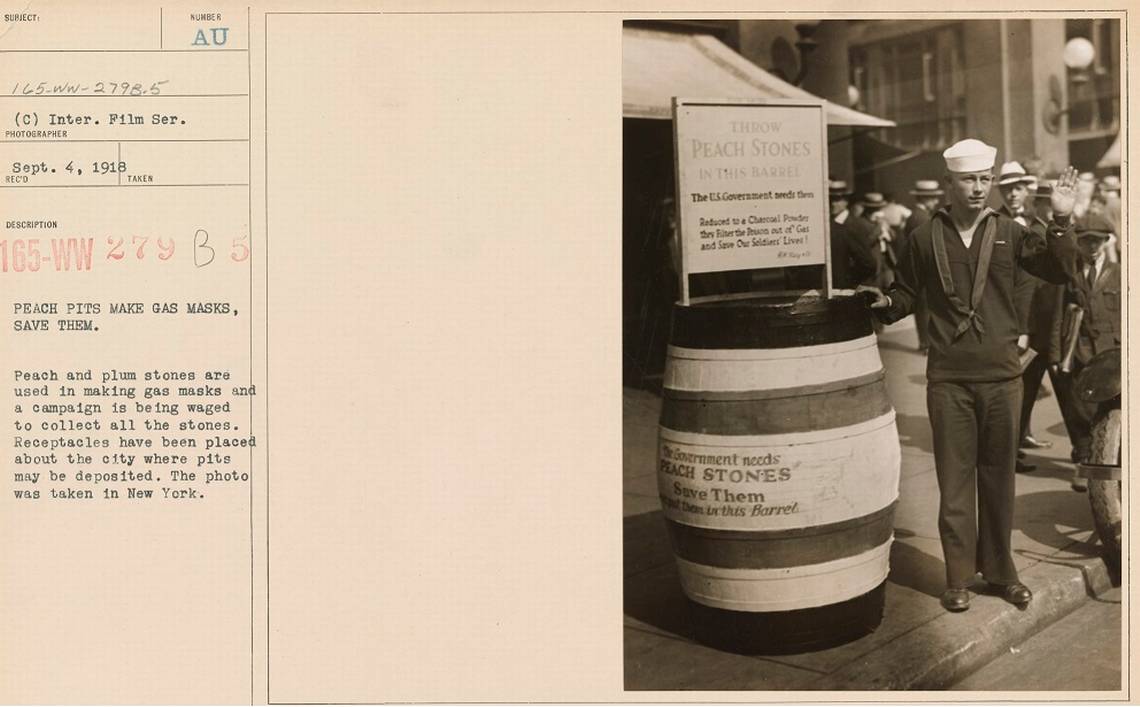

by Joan Lowenthal A 1918 call for supplies mirrors the health crisis today. The Red Cross made an urgent plea for masks for the doctors and nurses in quantities and at once. The Cold Spring Harbor branch spread the word that, “A special order for contagious ward masks has been received and the masks are being made at the Red Cross room and every evening in the Library. Members and their friends are urged to help with this work until the order is completed.” (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, October 04, 1918, Page 7) In 1918, not only was there a worldwide flu pandemic, but World War I was still being fought. Gas masks for men at the front line were desperately needed and the local Huntington Red Cross encouraged people to collect peach pits, nuts and other fruit pits also called stones and drop them into the receptacles found in several local stores. The government needed 750 tons of peach stones, plum stones, olive pits, and all hard nut shells especially coconut shells to supply charcoal for gas masks each day. The charcoal derived from these stones was forty times as strong as ordinary charcoal. Two hundred peach stones were needed for one gas mask. This was a nationwide nut-gathering campaign. (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, September 13, 1918, Page 1) By the beginning of October 1918 Huntington had done very well in saving their peach stones and other nut shells. Barrels and barrels were collected and shipped to a carbon plant where machinery ground up the bits and the material was distilled to uniform-sized carbon pieces. The powder was then shipped to the Gas Defense Plant New York located in Long Island City, NY where factory workers assembled gas masks. (Laura Corley. “How peach pits helped American allies win World War I,” The Macon Daily Telegraph, November 12, 2018.) People in the Huntington area responded so enthusiastically that it was not necessary to ask the Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls to canvas for nuts door to door. But these boys and girls were asked to pick up the peach stones in the local orchards. “There should be no peach stones left in the orchards doing no one any good, when they might save some precious life. (The Long Islander, Huntington NY , October 04, 1918, Page 2) There was an urgent appeal for nurses all over the country to replace the nurses that were sent overseas and to home military camps. The Long-Islander attempted to entice young women to become nurses. “The profession of nursing is one that should appeal to the ambition of young women fitted for the work; the pay is good and it is never overcrowded. In its higher branches it closely approaches the profession of the surgeon in its educational requirements.” The Long-Islander, Huntington, September 13, 1918.  The first wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic was fairly mild and many people recovered and the death rate was low. By the end of the summer of 1918 the second wave of the virus was virulent, highly contagious and deadly. In fact, the highest fatality rate of the pandemic was October 1918. Victims of the disease died within hours or days of developing symptoms and many were young adults. Local Long Island newspapers only mention the flu in the spring of 1918 infrequently, but by the fall especially in the month of October there are numerous accounts of local people dying and closings of churches, schools, and cancelling of events. The Jones family whose descendants started the Whaling Company in Cold Spring Harbor lost a member of their family due to the “Spanish Flu.” Philip Livingston Jones died at the Jones Manor Farm in Oyster Bay, NY. He was only 28 and left a wife and young son.(The Long Islander, November 01, 1918, Page 5). Sadly his mother Mary Elizabeth passed away the week before of a stroke at the age of 64 and his older brother Oliver Livingston Jones passed away the previous March at the age of 38. His death certificate lists bronchial pneumonia as the reason for death which were complications of the Spanish Flu. The devastating second wave of the “Spanish Flu” occurred in the US because returning soldiers infected with the flu spread it to the general population. Especially hard hit were densely populated cities. Many city governments were not ready for the onslaught. Philadelphia went ahead and had a Liberty Loan parade which was attended by tens of thousand of people. The disease spread like wildfire. In 10 days about 1,000 Philadelphians were dead and about 200,000 sick. By contrast citizens in San Francisco were fined $5 if they were caught in public without masks. The “Spanish Flu” took a toll on the economy. Even mail delivery and garbage collection was impeded and in many places there were not enough farm workers to harvest crops. Nonessential businesses were not mandated to shut down, but they were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Does history actually repeat itself? For more info check out:

5 Comments

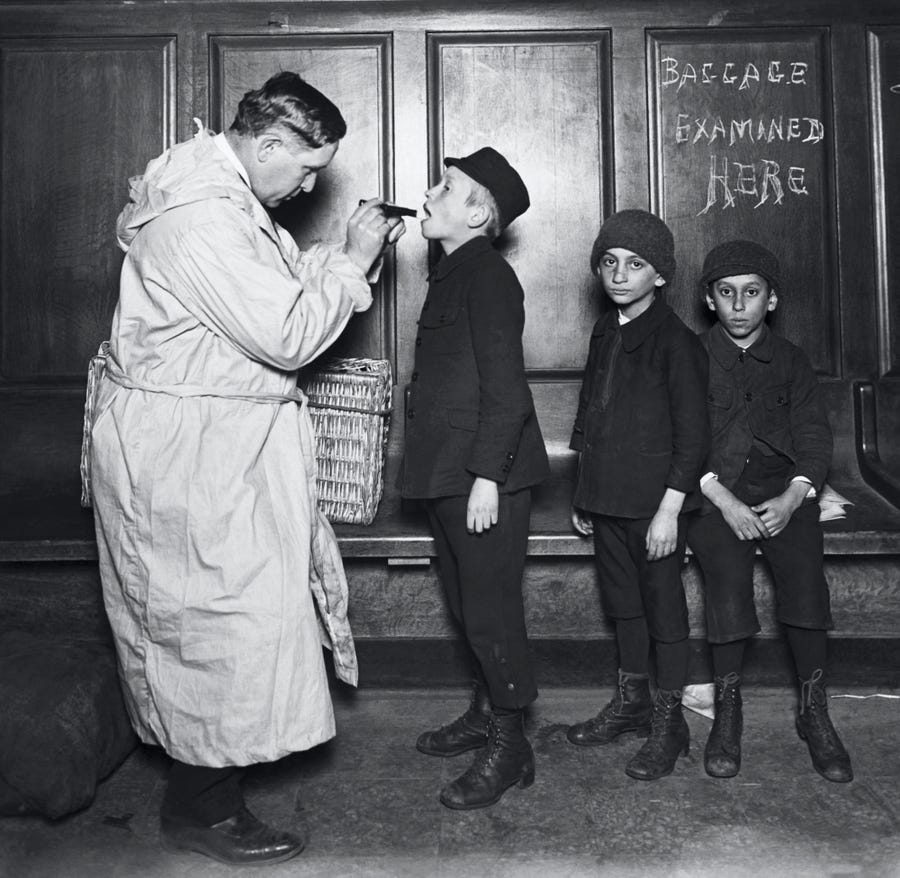

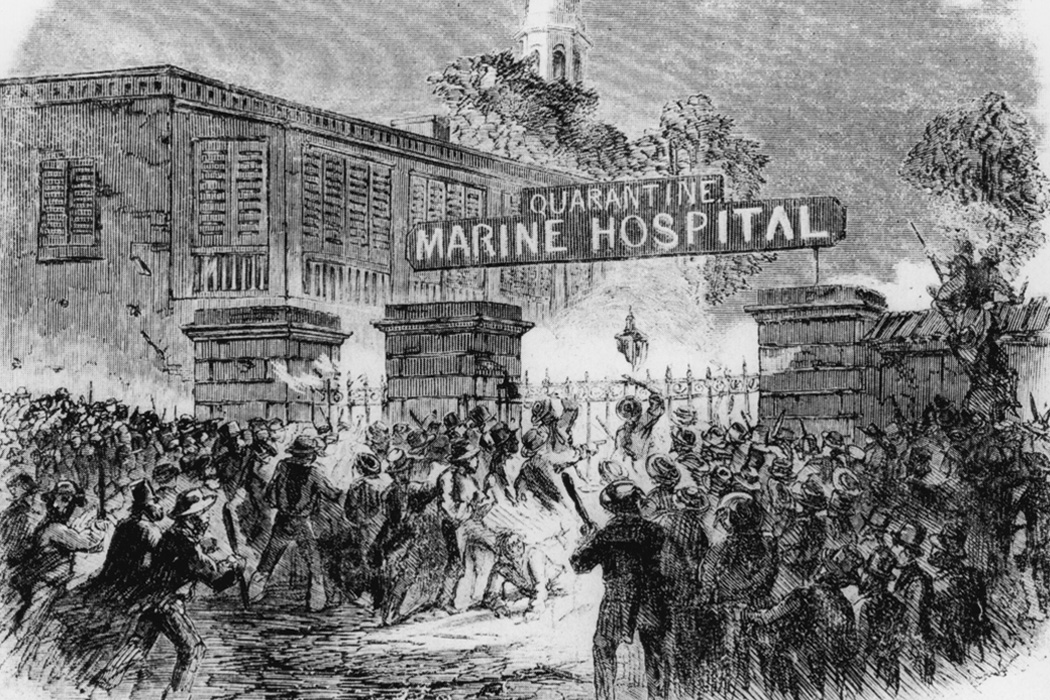

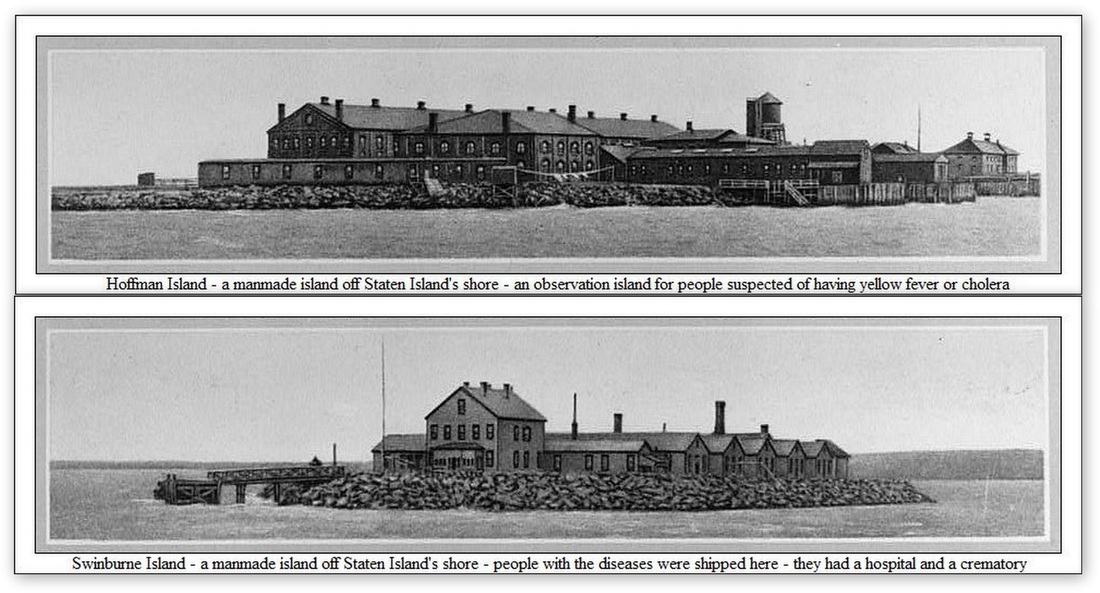

By Joan Lowenthal We are in unprecedented times. Many of us never thought a quarantine of practically the entire world could happen in 2020. It seems like science fiction.  14th century ship 14th century ship When did the practice of quarantine as we know it begin? It actually began during the 14th century as an attempt to protect coastal cities from plague epidemics. Ships coming into Venice from infected ports were mandated to sit at anchor for 40 days before anyone could come to shore. The word quarantine was derived from the Italian words quaranta giorni which means 40 days. When the United States was first established there was no federal involvement in quarantine regulations. It was not until 1878 that the United States Congress passed federal quarantine legislation. Up to this point protection against imported infectious diseases fell under local and state jurisdiction. By 1846 all ships coming into New York Harbor had to anchor off near Staten Island for quarantine inspection. The ships were boarded and if any signs of disease were found all the passengers were taken to the Quarantine Hospital on Staten Island which was opened in 1799 and called the Quarantine. First-class passengers were taken to St. Nicholas Hospital at the Quarantine and steerage passengers were taken to smelly, overcrowded bunkhouses stripped naked and disinfected with steaming water. [1] The ship then had to remain in quarantine for at least 30 days and sometimes as long as six months. There were as many as eight thousand patients in the hospital in a year. It was very dangerous work for the staff and funeral expenses for employees was a category in the accounting books. Many people who lived on Staten Island did not like the nearness of the hospital and in 1858 angry well-prepared vigilantes set fire to the buildings. Two people died that night. Check out When New Yorkers Burned Down a Quarantine Hospital by Matthew Wills (September 19, 2019) daily.jstor.org. Quarantine facilities were then moved off-shore to a boat named after Florence Nightingale, then two islands off of Staten Island. The two islands were built with land fill in the Lower Bay - Swinburne Island in 1860 and Hoffman Island in 1873. These small islands were used as quarantine islands until the 1920s. The conditions were horrifying. Today these islands are uninhabited and off limits to the general public although you can go past them in a boat. In the summer of 1892 there was a terrible cholera epidemic and several ships that came from Hamburg, Germany were kept quarantined. Many of the people on board were refugees from Russia fleeing the reign of Czar Alexander III. A cholera epidemic swept through Russia and passengers both in steerage and cabin class died from the disease during their voyage. They were seeking a better life in the United States. What is little known is that the Governor of New York at the time, Governor Flower, authorized the purchase of the Surf Hotel, an aging hotel on Fire Island to be used as a quarantine station for some of the passengers from the infected cholera ships in New York Harbor. There was tremendous opposition and two hundred deputized officers of the Islip Town Board of Health tried to stop the passengers from getting off the ship. The Islip Town Board of Health disputed the right of the State to use the island as a quarantine station. [2] Local baymen feared their livelihood was at stake when oyster houses in New York City began cancelling orders. According to Shoshanna McCollum in an article posted February 23, 2020 “600 healthy cabin class passengers of the Normannia were transferred to a day boat to take the passengers to the Surf Hotel. Unfortunately the baymen turned vigilantes and crossed the bay with clubs and shotguns.” The trip should have taken the day boat several hours, but instead took several days. This must have been awful as the boat was overcrowded and did not have sleeping accommodations nor enough food provisions. Troops were sent by Governor Flower to Fire Island to permit the asymptomatic passengers to disembark. The Surf Hotel served as quarantine headquarters until early October of 1892. Amazingly only two documented cases of illness were reported on Fire Island during this time and those two cases turned out not to be cholera at all. One other interesting note about the Surf Hotel. The owner of the hotel at the time was David Sammis and he sold the hotel to the state for $210,000 which is a value of about $60 million today. This was definitely over-priced. Check out the article by Shoshanna McCollum Plague & Prejudice When Quarantine Came to the Shores of Fire Island. fireisland-news.com There have been pandemics throughout history, but probably the most famous at least up to this point has been the 1918 Flu Pandemic also known as the Spanish Flu. It lasted from January 1918 to December 1920 and as reported by the CDC it was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It infected about 500 million people which was about a third of the world’s population at the time and killed at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,00 occurring in the United States. cdc.gov 1918 Pandemic (H1N1) virus) Many people on Long Island were affected by the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Just one page in The Long-Islander, October 25, 1918, Page 6, Image 6 describes the state of affairs. In Huntington Station “Garrett Van Wicklen, who has been with influenza, was improved, but this week suffered a relapse from which he is recovering.” “The influenza is quite prevalent here this week, and in one family there were four ill with it.” “Owing to the epidemic it has been deemed wise to indefinitely postpone the dance of the Huntington Manor Firemen, which was to have been held in Liederkranz Hall Saturday evening.” “In effort to help the health authorities to stamp out the influenza, no churches were open in this section Sunday. In order that his people should not be deprived of worship, the Rev. Francis X Wunsch had an altar erected on the lawn adjoining St. Hugh’s R.C. Church and celebrated mass out of doors.” “The Greenlawn School is closed by order of the Board of Health during the influenza epidemic. As today, nurses during the Spanish Flu Pandemic galvanized and worked extremely hard putting their own health in peril to save victims of the Spanish Flu. One of these nurses was the daughter of George W. Barrett of Cold Spring Harbor who trained on Cold Spring Harbor whaling ships, The Alice and The Sheffield. The Long-Islander, December 13, 1918, Page 7, Image 7 states that “Miss Laura G. Barrett, who has been visiting her sister has returned to her work at the Henry Street Settlement in lower New York City. When the dreadful Spanish Influenza struck New York City, Miss Wald, who is at the head of the Henry Street Settlement, offered her large staff of 150 nurses to the city. During the time the epidemic raged the amount of work the Settlement was called upon to do was very heavy and taxed them to the utmost. Miss Barrett had much responsibility in her office and was given a short leave of absence for complete rest and has been much benefited by her stay in Cold Spring Harbor.” There was good advice in The Long Islander, October, 4, 1918:

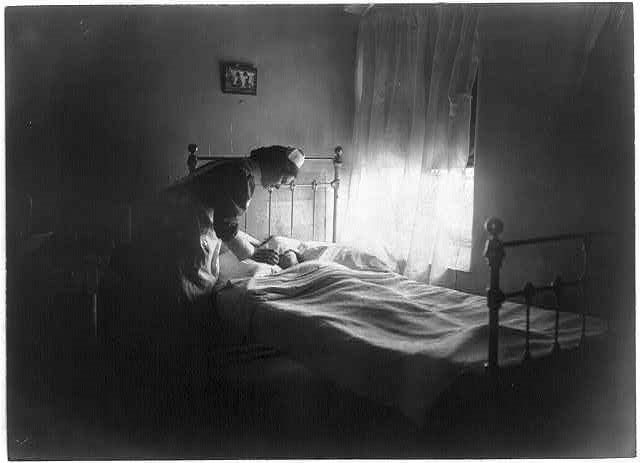

“HEALTH PRECAUTIONS: Don’t get frightened after reading that learned dissertation in our columns this week on Spanish Influenza and take to your bed. It is after all the old-fashioned grip and every time you cough or sneeze it does not signify you are going to have it. Keep your courage up and avoid overcrowded cars and other meeting places. Do not get too tired from overwork and eat moderately. Live in the open air as far as possible.” This is probably good advice for today, too. In Celebration of National Nurses Week: May 6-12, 2019By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director of The Whaling Museum of Cold Spring Harbor ***In honor of National Nurses Week, the museum is offering pay-as-you-wish admission for nurses (with current ID) and their families (up to 6 people) from Tues-Sunday, May 7-12 2019 as the museum recognizes the importance of nursing roles which whaling wives often took in the whaling industry.*** Becoming ill is never fun. Becoming ill when away from home is worse. And becoming ill at sea on a whaling ship is the worst of all. “Let a man be sick anywhere else - but on shipboard,” wrote whaler Francis A. Olmstead in 1841 in Incidents of a Whaling Voyage. Whalers who fell ill could find little comfort. Francis continued to explain, “When we are sick on shore, we obtain good medical advice, kind attention, quiet rest, and a well ventilated room. The invalid at sea can command but very few of these alleviations to his sufferings.” There were no ‘sick days’ for whalers, who were expected to work during busy times if they could stand. The incapacitated whaler would lie on his grimy, cramped straw mattress in his misery, listen to the nonstop creaking of the ship, roll from side to side with the swaying of the ship, and breathe the fishy, putrid air. He would eventually be visited by the “doctor,” a.k.a. the captain. The skipper would rely on his weak medical and surgical knowledge as he opened his medicine chest and offered some powdered rhubarb, a little buckthorn syrup, or perhaps mercurial ointment, chamomile flowers, or cobalt. The whaler would then either recover or die. If he passed, the captain would casually mention his death in the next letter home, and perhaps pick up a replacement at the next port. If the whaler was lucky, he might awaken from his burning fever and shivering chills to hear a soothing voice, feel a cool cloth being gently placed on his forehead, and perhaps taste a bit of food offered to him. He would sit up to catch a glimpse of this angel visiting him with her wide skirt and billowing sleeves.

Most wives were happy to feel valuable and help contribute to the voyage’s success. Some took the initiative to go beyond their nursing roles: Calista Stover of Maine persuaded the crew of a sailing ship to swear off tobacco and alcohol while in port (the pledge didn’t stick). Others tried to reform men’s swearing. However women tried to improve the crew, their support gives understanding to the root of the word “nurse,” which is Latin for nutrire – nourish. No wonder Charles. W. Morgan wrote, “There is more decency on board when there is a woman.” EXPLORE MORE

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed