|

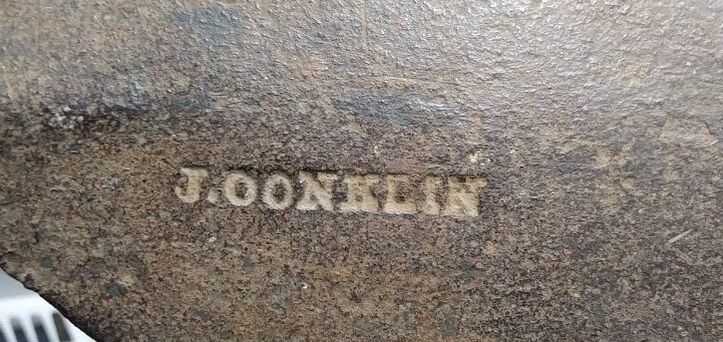

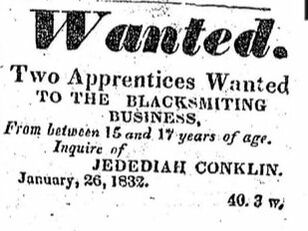

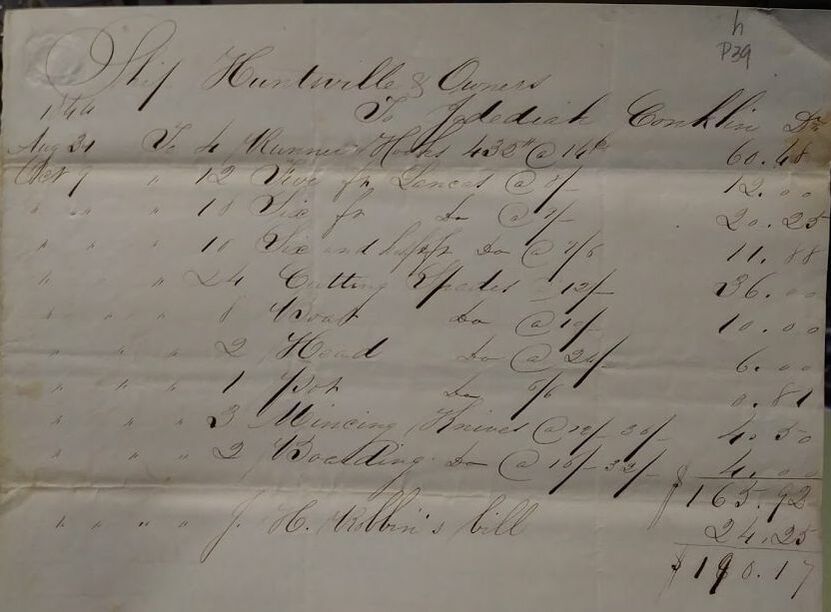

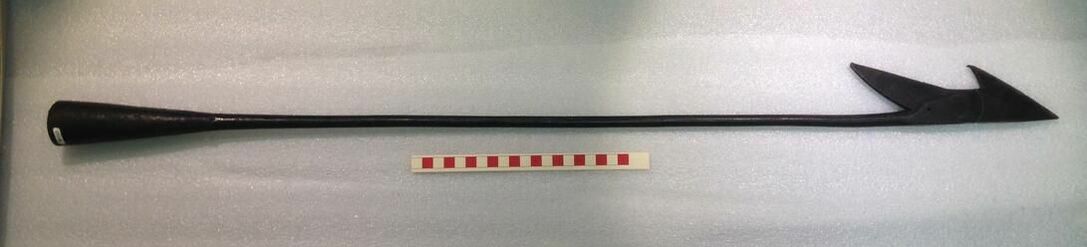

Whaling Museum Acquires 4 Artifacts of Jedediah Conklin: Master Blacksmith, Gold Digger, and Oldest Resident of Sag Harbor by Nomi Dayan, Executive Director The Whaling Museum recently acquired 4 objects into its collection, one harpoon and three boat spades, dated from the 1820’s-50’s. All objects had a maker’s mark: “J. Conklin.” Who was he? Jedediah Conklin was born in Amagansett on February 17, 1798 to Henry Conklin and Esther Baker. His Conklin side (sometimes spelled Conkling) could be traced back to one of the four original families who broke away from comfortable East Hampton to bravely start new families in what was then the wilderness. Given the same name as his uncle, Jedediah was baptized that June. His parents let no disciplinary opportunities slide, as he later recounted: “My people never spare the rod and spoil the child; my father whipped me today for throwing stones at my grandfather.” Henry likely chose Jedediah’s trade for him, and he chose well: blacksmithing, a highly skilled occupation held in the highest esteem. In an era when each nail and each link in a chain was handmade, this trade was in high demand in many communities at the time – and perhaps Sag Harbor most of all as the village boomed into the 5th largest whaling port in the country. Young Jeremiah learned to work with extreme heat for twelve-hour shifts, pounding a heavy sledge over glowing-red metal, sparks bouncing off his thick leather apron. Over the heat of fire, he used his strength and knowledge to perfect the transformation of iron into whatever tool his customers demanded. Those items were whaling gear: arrow-straight harpoons, razor-sharp lances, flat cutting spades, and barrel hoops, all designed to bring back the richest oil the world had ever known. Into each of his creations, he stamped his maker’s mark: J. CONKLIN. Jedediah’s career bloomed marvelously with the golden age of whaling. Sag Harbor was thriving, and he was the mechanical backbone of it. With a good job and steady income, he married Frances Puah Terry (b. 1807) of Aquebogue in his mid-twenties. For the first time, he appears as Head of Household on the 1830 census. The earnings of a blacksmith were lucrative, but chasing people to settle their bills was another matter. In 1831, he placed an ad in the paper informing “all those who are indebted to him, or whose accounts with him are unsettled” that unpaid debts will be placed in the hands of an attorney for settlement. No doubt he needed the money: his family would quickly grow to have six children: John Barker, Dorliska, Catherine, Henry, Evelyn, and Mary. In 1832, he took the career-affirming step by advertising his desire to take on two young apprentices, who would agree to work for a number of years to learn the “art and mystery” of the trade. One of his apprentices was John Fordham, who was only 12 when he became Jedediah’s apprentice, sleeping in the attic with mice running over his legs. In his late teens, John progressed to earn a dollar a day, and continued to work for Jedediah after he married (and later even purchased his shop). His apprenticeship served him well, because John became an expert smithy who at one point employed 12 men in his shop. Business continued to grow. Jedediah could hardly get harpoons out fast enough as demand for blacksmiths soared. After moving several times, in 1833 he purchased a lot near the water in Sag Harbor measuring 60 feet by 100 feet for $135. Soon, whaling companies not only in Sag Harbor were relying on him, but the relatively new Cold Spring Whaling Company paid him for lances, an assortment of spades, hooks, and knives for the Tuscarora’s 1843 voyage and again in in 1844 for the Alice and newly purchased Hunstville. He wasn’t the only blacksmith on the block: that same year, new neighbor John Cook, a fellow blacksmith, planted himself right next to Jedediah and advertised his harpoons and whale craft sold from his blacksmithing shop “opposite the shop of Jedediah Conklin.” Although there was more than enough work to go around, the close competition didn’t matter, because Sag Harbor suffered an epic and disastrous fire the next year on a windy November morning in 1845, wiping out provisions just before winter. Both blacksmith shops were reduced to ashes among 95 other buildings. 40 families were homeless. Sag Harbor was not the same after the fire. Although the whaling industry peaked over the next few years, the trade declined into a collapse shortly after. Jedediah himself was also perhaps not the same: his eldest son John died at the age of 21 in September 1848. He likely tried to throw himself into his work, but less people were waiting in line for his harpoons. When gold fever swept through Long Island, Jedediah was no exception among the Sag Harbor men whose imaginations were hit hard. He joined a group of men from Sag Harbor and the Hamptons who formed the Southampton and California Mining and Trading Company and became one of 60 excited stockholders. If Jedediah hadn’t learned to swear well by then, he certainly picked it up from the 16 whaling captains aboard. After supper one day, he was standing mid-deck chatting with several others when the person at the ship’s wheel played a trick and angled the ship to meet a good-sized wave, which doused Jedediah. The reteller of the story said, “I cannot repeat his language, but you may suppose - it was no song of praise.” Two weeks out, the Sabina began to leak in the middle of the Atlantic, but the seasoned crew kept going. The Sabina finally arrived in San Francisco in August 1849. As described by a fellow crewmember, Jedediah saw busy harbor which “resembled New York on the Pacific… The buildings are of the frailest and cheapest kind. A great many businesses operate under large tents… We shall probably start as soon as Monday for the diggins.” The crew raced into the wilderness, sleeping in an enclosure made with a tier of logs and blanket for a roof. No doubt Jedediah’s muscular pounding arm came in useful for digging. Life quickly turned difficult. Not only was there no gold, but men starting getting sick, and Jedediah stayed with the ill in Sacramento as other hired wagons and mules to search further. Just one month after arriving, the team decayed; it was now every man for himself. After half a year, Jedediah gave up for good and departed home January 23, 1850, his golden dream gone, the Sabina sadly abandoned in port to rot. Life moved on – and in exciting ways. While Jedediah was in California, the whaling world had been taken by storm when Lewis Temple, a freed slave and New Bedford blacksmith, improved the toggle harpoon in 1848, dramatically increasing whalers’ success at sea. This tool quickly became the standard in the industry. Jedediah must have studied this curious hinged barb with excitement; he fired up his forge again and tried his own hand copying this design, which he was free to do, as no patent had been filed. When the harpoon was complete, he didn’t know where to press his maker’s stamp. As if out of respect for the new design, he chose an unusual spot – low down on the harpoon’s shank. He then slathered the iron in red primer, followed by a thick black coat of paint, and placed his proud harpoon for sale. The object never found a buyer. It quietly sat on a shelf collecting dust as buyers reached past it for other things. No matter - Jedediah had other inventions up his sleeve. In 1854, he announced “Lightning Rods!” were for sale, acting as agent for the east end. He promised a conductor “uniformly pronounced by scientific men to be the safest and best means of protection against lightning ever offered to the public.” Jedediah continued his progressive stance by sending at least one of his daughters to school. Flushing Female College, an institution “for the solid and ornamental education of Young Ladies,” listed Jedediah as a reference in 1855, along with fellow Sag Harbor whaling Captain Wickham Havens, who also sent his daughter there. For the first time, Jedediah’s family started thinning: Dorliska married in 1857, and Catherine followed in 1859; his second son, Henry, died in his early twenties in 1864. Jedediah decided to downsize, sell his house, and rent elsewhere. In 1866, he advertised the sale of a “two story dwelling house, situated on Division Street, and nearly opposite the rear of the store of William H. Tooker,” a merchant of a country store. Even as Jedediah aged, he continued adapting to a world where he was not needed to build tools anymore; factories were taking care of that. He turned his attention to the next big thing – machine and equipment repair. He announced in the newspaper in 1860 that in addition to his former business, he was partnering with his old apprentice John Fordham “to do all kinds of Machine work, especially repairing Horse Powers, Mowing Machines, Thrashing Machines, all of which will be done in the best possible manner, and warranted to give satisfaction.” His shop continued to rent space to other blacksmiths. One advertised in 1869 that he was working in Jedediah’s shop repairing stoves, flat irons, locks and keys, tools, and farming work, machines and wagons. In 1871, Jedediah advertised that he was selling axes, stalk-hoes, and wagon tires. He also advertised selling 2,000-3,000 second hand bricks, which possibly came from the rear and east wall of his shop which caved after a bad storm, which he promised to sell at a good price. Jedediah likely noted the good price because Sag Harbor was in a depression. In the 1870’s, the neighborhood was described as “one deserted village – a seaport from which all life has departed.” Nevertheless, Jedediah hung on and continued to branch out by becoming an owner of the Mansion House, a four-story stately 1846 building built with Philadelphia pressed bricks. In the Long Island and Where To Go publication by the LI Railroad Company in 1877, “Mrs. Jedediah Conklin” was listed as a good place to stay. In the 1880’s, he became a trustee of the Sag Harbor Savings Bank, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. Jedediah watched the world continue to change around him as new technology and mass production edged out the once-secure blacksmithing craft. Although he had weak eyes later in life, Jedediah seemed to outlast everyone around him, with newspapers calling him a “conspicuous example of Long Island longevity.” Half of his children (that we know of) died in his lifetime. His wife died suddenly in 1885 after falling in a fit while cleaning the house. But Jedediah kept going: in 1890, he found himself the oldest person in the township. Oldest or not, he continued to stay active, and not even ice would hold him back. The Newton Register noted on a frigid March day in 1890: “From Sag Harbor: Notwithstanding the mercury ranged down about ten degrees on Friday, and our streets were glazed with a coating of slippery ice, one of our vigorous old citizens was seen making two or three trips up and down one of our thoroughfares. Mr. Jedediah Conkling is 93 years old, and yet hale and hearty and active as many men at twenty his junior.” He must have loved walking, because that year the newspaper reported he walked 5 miles to Hardscrabble. His active lifestyle came to an end one Saturday morning when he got up from his chair and fell, stricken with paralysis. Bruised and unconscious, he died the following Wednesday on April 8, 1891 at 93 years old, 1 month, and 22 days. The bank noted he was “known and honored by us all for his personal kindness, for his unfailing zeal,” and “he was the gift of the eighteenth century to the nineteenth.” He was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor. His surviving grandchildren blew around the country, including Oregon and Minneapolis. After Jedediah’s passing, his creations remained behind – those rods of iron he painstakingly and masterfully fashioned for whaling voyages were now on collectors’ shelves. One collector was Bob Hellman of Nantucket, a scholarly enthusiast of whaling gear. After he passed away in 2018, his wife Nina Hellman, owner of a marine antiques shop who had appraised the museum’s collection years back, privately sold the items at a reduced price to the museum. While the portraits of whaling captains often get the glory of our country’s long history of whaling, those silent maker’s stamps frozen into iron are lasting testaments to blacksmiths’ essential contributions to the industry. Before whalers’ eyes could scan the seas for whale spouts, they first visited East Water and Main Street in Sag Harbor and waited, just as Melville described the blacksmith in Moby Dick: "Often he would be surrounded by an eager circle, all waiting to be served; holding boat-spades, pike- heads, harpoons, and lances, and jealously watching his every sooty movement, as he toiled." Thank you to Rebecca Grabie of the John Jermain Memorial Library for research assistance. References Armbruster, Eugene L. Amagansett / Wainscott, Long Island: Jedidiah Conklin House, north side of Main Street.. 1923. New York Historical Society, New York. Eugene L. Armbruster photograph collection, 1894-1939. Series II: New York City Negatives Brewster-Walker, Sandi. The gold rush of 1849: we got a little gold! Part 2. Amityville Record. February 17, 201. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb 25 1889 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 17 1889 Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Many Long Island Men Among Gold Seekers in 1849. October 26, 1849 The East Hampton Star. (East Hampton, N.Y.), August 09, 1929, Page 6, Image 6 The East Hampton Star. (East Hampton, N.Y.), July 25, 1940, Page 2, Image 2 Conklin, Joseph Inglish Jr. Copy of Conklin genealogy 1875-1908. Presented to the Huntington Historical Society through Tarrytown Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution, Copied from the original February 1947 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), June 11, 1831, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), February 09, 1833, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector., (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), October 27, 1838, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), April 20, 1844, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), July 29, 1854, Page 4, Image 4 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), September 01, 1855, Page 3, Image 3 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 16, 1891, Page 2, Image 2 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 2, 1885 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), May 23, 1885, Page 2, Image 2 The Corrector. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), February 26, 1910, Page 5, Image 5 The County Review., (Riverhead, N.Y.) August 15, 1924, Page 9, Image 9 Field, Louise M., ed. Amagansett: Lore and Legend. 1948. Amagansett Village Improvement Society. Amagansett, NY. Islip Bulletin., (Brentwood, N.Y.) May 16, 1974, Page 12, Image 12 Mallmann, Jacob E. Historical Papers on Shelter Island and Its Presbyterian Church. 1899. Shelter Island, NY. Newton Register, March 13, 1890 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), June 27, 1867, Page 3, Image 3 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.) Feb 17, 1870 Sag-Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), August 31, 1871, Page 3, Image 3 Sag Harbor Express., (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), April 03, 1952, Page 2, Image 2 Sag Harbor Express. (Sag-Harbor, N.Y.), August 31, 1972, Page 1, Image 1 Sag Harbor Express. (Sag Harbor, N.Y.) May 14, 2015, Page 9, Image 9 The Traveler. April 17, 1891. Southhold, NY. Obituary Wiley, Nancy B. John Fordham, Harpoon Maker. Aug 1851. Long Island Forum. Additional: Whaling Museum Archives

4 Comments

Norwegian-American whaling captain C. T. Petersen climbing the rigging, circa 1935. Courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum Norwegian-American whaling captain C. T. Petersen climbing the rigging, circa 1935. Courtesy New Bedford Whaling Museum By Joan Lowenthal Recently a visitor to the Museum was reading an excerpt from the displayed logbook of the whaleship the Sheffield. He read that on Thursday, May 21st, 1846 while taking in sail at sunset, Scudder Abbott, a crew member on the Sheffield, lost hold and fell about 70 feet from the topsail yard to the deck. He became delirious and blood ran from his mouth and nose. He was immediately taken to the cabin and bled and made as comfortable as possible. The next day he was at times sensible and then again quite deranged. The visitor wanted to know if Abbott survived the fall. Did he? Whaleships and the nature of the whaling industry were dangerous, and the Sheffield was no exception. She was the largest whaler sailing out of Long Island, and the third largest whaler in the US. She was purchased in 1845 by the Cold Spring Whaling Company and boasted an impressive history of speedy, having broken records by crossing the Atlantic in only 16 days. Onboard whalers, there were commonly shipboard accidents, fighting, illnesses, food poisoning, drowning, and of course the dangers of hunting a powerful whale. Captains were responsible for dealing with illnesses and injuries aboard. They used their limited medical knowledge and supplies from the onboard medicine chest. Starting in 1790, the medical chest was part of legal required equipment on all American ships of 150 tons or more with ten or more people on board. The chest contained vials of drugs from powdered rhubarb to arsenic, identified by numbers which corresponded to recommendations outlined in a list of symptoms. During a time when doctors may not have been much more knowledgeable than the captains themselves, many times the treatments were worse than the injury or illness! After Scudder Abbott fell, as the logbook records, he "was taken up senseless in the cabin and bled and everything that we know of to make him comfortable." Considered one of medicine’s oldest practices, bloodletting was the standard treatment for various diseases. The logbook continues to document his recovery. The following day, he was "at times sensible and then again quite deranged." On Saturday, May 23, 1846, Abbott was "still out of his head but he was able to sip some soup and drink some sage tea." Sage tea has been used medicinally throughout history to help improve a variety of health issues. Two days later, the logbook records light squalls of wind and rain, and states Abbott seemed more rational and appeared to be “in the gaining hand.” Thursday, May 28th, after noting fog and unpleasant weather, the logbook records: “The invalid Abbott is much the same as yesterday, rather stronger but rather out of his head.” Abbott is briefly mentioned thereafter. On Sunday, June 14th, 1846, the logbook states, "Right Whales were chased sometime without success. Abbott was well enough to stay on deck all day for the first time since he fell from aloft." But the very next day, he remained forward in his bunk. The last entry about Abbott was on Friday, October 8th, 1846. The logbook simply stated that "S. Abbott rather better." Nothing is known about Abbott past this point, even after searching crew lists. With his lucky survival, he quietly vanished back into the workforce of thousands of crew members who faced incredible and serious risks in order to light the world. For more information on medical practices on board a whaleship check out Hen Frigates Passion and Peril, Nineteenth-Century Women at Sea by Joan Druett (A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster, 1998).  By Nomi Dayan Whaling was a risky business, physically and financially. Life at sea was hazardous. Fortunes were made or lost. Whalehunts were perilous, as was the processing of the whale. Injuries were rampant and death was common, sometimes on nearly every voyage. In some instances, the deceased was none other than the captain. Captain Sluman Lothrop Gray met his untimely end on a whaleship. Born in 1813, very little is known of his past, his family, or his early experiences at sea. In 1838, he married Sarah A. Frisbie of Pennsylvania in the rural town of Columbia, Connecticut. His whaling and navigational skills must have been precocious, because in 1842, in his late twenties, Gray became a whaling captain – and a highly successful one. His wife, Sarah, joined him in his achievements, living with him at sea for twenty years. Three of their eight children were born during global whaling voyages. Gray commanded a string of vessels: the Jefferson and Hannibal of New London, CT to the Indian and North Pacific Oceans, the Mercury and Newburyport of Stonington, CT to the South Atlantic, Chile, and Northwest Pacific Oceans, and Montreal of New Bedford, MA to the North Pacific Ocean. While financially successful, Gray’s crew felt his harsh personality left much to be desired. Some of his blasphemies were recorded by a cabin boy on the Hannibal in 1843. He did not hesitate to flog crew members for minor mistakes. Unsurprisingly, when Sarah reported her husband had taken ill, the crew rejoiced. (To their chagrin, he recovered.) As Gray aged, he attempted to retire from maritime living and shift into the life of a country gentleman. He bought 10 acres of land in Lebanon, Connecticut and lived there for 7 years, where his house still stands. This bucolic life did not last, and Gray returned to whaling. With his wife and three children – Katie, Sluman Jr., and Nellie aged 16, 10, and 2, he sailed out of New Bedford on June 1, 1864 on the James Maury. Built in Boston in 1825 and sold to New Bedford owners in 1845, the James Maury was a hefty ship at 394 tons. Gray steered the course towards hunting grounds in the South Pacific. Unexpectedly, after nine months at sea in March 1865, he suddenly became ill. The closest land was Guam - 400 miles away. Sarah described his sickness as an “inflammation of the bowels.” After two days, Captain Gray was dead. The first mate reported in the ship’s logbook: “Light winds and pleasant weather. At 2pm our Captain expired after an illness of two days.” He was 51 years old. Sarah had endured death five times before this, having to bury five of her children who sadly died in infancy. She could not bear to bury her husband at sea. Considering how typical grand-scale mourning was in Victorian times, a burial at sea was anything but romantic. It was not unheard of for a whaling wife to attempt to preserve her husband’s body for a home burial. But how would Sarah embalm the body? Two things aboard the whaleship helped: a barrel and alcohol. Sarah asked the ship’s cooper, or barrelmaker, to fashion a cask for the captain. He did so, and Gray was placed inside. The cask was filled with “spirits,” likely rum. The log for that day records: “Light winds from the Eastward and pleasant weather; made a cask and put the Capt. in with spirits.” The voyage continued on to the Bering Sea in the Arctic; death and a marinating body did not stop the intentions of the crew from missing out on the summer hunting season. However, there was another unexpected surprise that June: the ship was attacked by the feared and ruthless confederate raider Shenandoah, which prowled the ocean burning Union vessels, especially whalers (with crews taken as prisoners). The captain, James Waddell, had not heard – or refused to believe - that the South had already surrendered. When the first mate of the Shenandoah Lieutenant Chew came aboard the James Maury, he found Sarah panic-stricken. The James Maury was spared because of the presence of her and her children – and presumably the presence of her barreled husband. Waddell assured her that the “men of the South did not make war on women and children.” Instead, he considered them prisoners and ransomed the ship. 222 other Union prisoners were dumped onboard the ship and sent to Honolulu. One can imagine how cramped this voyage was since whaleships were known for anything but free space. A year after the captain’s death, the remaining Gray family made it home in March 1866. The preserved captain himself was shipped home from New Bedford for $11. Captain Gray was finally buried in Liberty Hill Cemetery in Connecticut. His resting place has a tall marker with an anchor and two inscriptions: “My Husband” and “Captain S. L. Gray died on board ship James Maury near the island of Guam, March 24, 1865.” Sarah died twenty years later, and was buried next to her husband. It is unknown if Gray was buried “as is” or in a casket. There are no records of Sarah purchasing a coffin. Legend has it that he was buried barrel and all. Nomi Dayan is the Executive Director at The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor, NY. Read More:

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed