|

What's cookin'? How about Joe Frogger cookies? While developing content for our new special exhibit, "From Sea To Shining Sea: Whalers of the African Diaspora," museum staff came across a recipe for for an oversized ginger cookie dating back to colonial times -- the Joe Frogger Cookie. The cookie's creation is attributed to Lucretia Young, who was born in 1772 to two formerly enslaved people in Marblehead, Massachusetts, a seaport. She married Joseph Brown, the son of an African American mother and Wampanoag Nation father, and who had been born into slavery to Rhode Island sheriff slaveowner Beriah Brown II. Little is known of Joe's early years, but he enlisted as a soldier in the Revolutionary war to take the place of his enslaver's son, who Joe said "left the company to go privateering." Beriah promised his liberty if he would serve out his son's time. Joe completed his enlistment in 10 months and 20 days, serving with 60 other men, and left the war a free man. During a time when unemployed freed Black people had to leave Marblehead, Lucretia and Joe operated a successful and busy tavern serving sailors. The building still stands today. There, Lucretia mixed sea water, rum, molasses, and spices to create a large, gingerbread-like cookie which sailors bought by the barrel - The Joe Frogger. While the exact origin of the name is unclear, as legend has it, she named the cookie after her husband and the nearby pond's wide, flat lily pads. Because the cookies lacked milk or eggs, the rum-preserved cookies had a long shelf life suitable for sea voyages, and were popular with fishermen and sailors. Joe and Lucretia were free people and property owners in a time when most African Americans were enslaved, yet its star ingredients— rum and molasses—are inextricably tied to the brutality of slavery.

Find out more about Joe and Lucretia's life, including archival materials, from a post by the Marblehead Museum. By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director

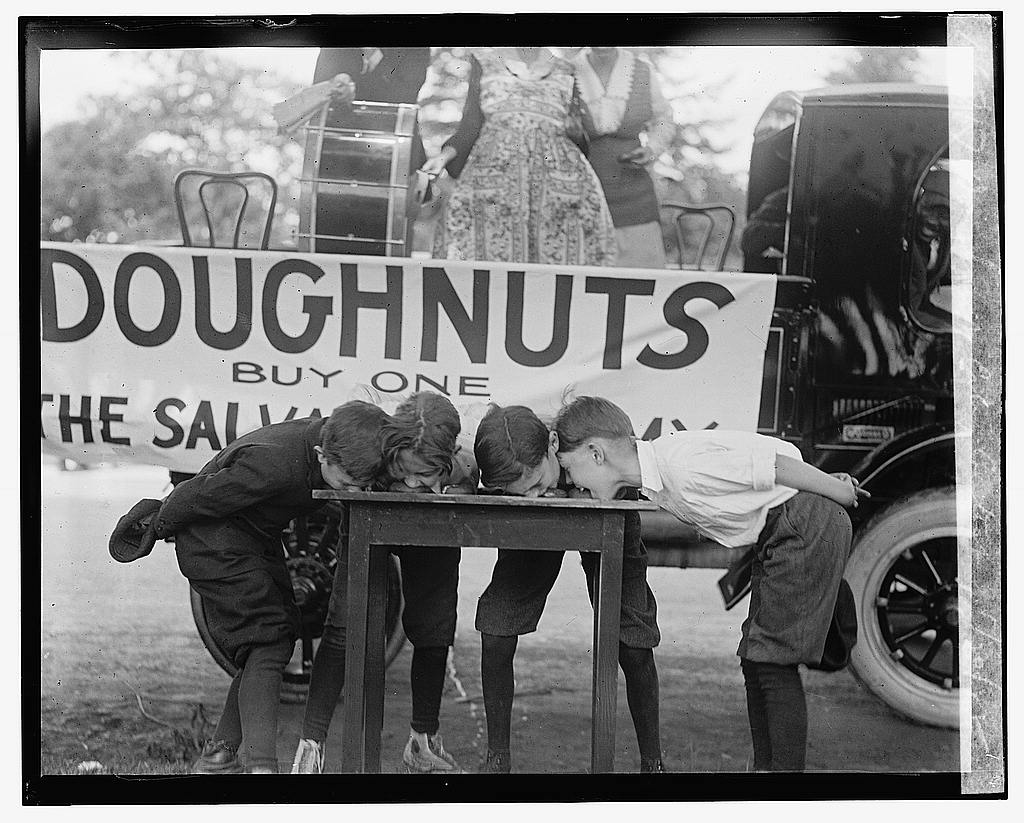

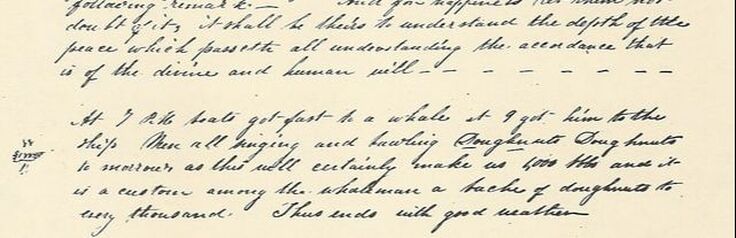

The cook would have then passed the dough on to the crew on deck, who took care of the cooking. The fritters were deep-fried in none other than whale oil in trypots - enormous, black cauldrons filled with shimmering whale oil rendered from whale blubber. The dough balls were lowered into these vats of oil, the crew watching them bob in the boiling gold before lifting them out with a skimmer. This long-handled strainer was designed to separate blubber from oil, but was perfectly suited for lifting doughnuts out as well. The crew would have wiped their dirty hands on the backsides of their pants and closed their eyes as they bit into these fresh, hot, puffy doughnuts, literally eating their bounty - a welcome change from the monotonous, paltry fare normally served on a whaleship. Several whaling wives who traveled with their husband-captains at sea recorded the serving of doughnuts. On Sunday, July 26, 1846, Mary Brewster wrote in her journal, “At 7PM boats got fast to a whale, at 9 got him to the ship. Men all singing and bawling [boiling] Doughnuts, Doughnuts tomorrow, as this will certainly make us 1000 bbls [barrels] and it is custom among the whaleman a bache [batch] of doughnuts to every thousand. Thus ends with good weather.” The next day, she noted, “This afternoon the men and frying doughnuts in the try pots and seem to be enjoying themselves merrily.” On another occasion, Henrietta Deblois stepped in to help with the cooking process. She recorded on the Merlin in 1858: “Today has been our doughnut fare, the first we have ever had. The Steward, Boy, and myself have been at work all the morning. We fried or boiled three tubs for the forecastle [sleeping area for crew] - one for the steerage. In the afternoon about one tub full for the cabin and right good were they too, not the least taste of oil – they came out of the pots perfectly dry. The skimmer was so large that they could take out a 1/2 of a peck at a time. I enjoyed it mightily." While whale oil was typically off-tasting, those who ate the donuts described only deliciousness. One exception was missionary Betsey Stockton, who sailed on a whaler to Hawaii in 1822. She wrote, “The crew [is] engaged in making oil of two black fish [whales] killed yesterday… we have had corn parched in the oil; and doughnuts fried in it. Some of the company liked it very much. I could not prevail on myself to eat it.” Keep an eye out for special offers from local donut shops in celebration of this day!

Read More:

By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director As you reach for a sweet treat this June in honor of National Candy Month, consider how the abundance of candy today is a rather exceptional thing. For much of human history, sugar was an expensive indulgence reserved for celebratory desserts. Sugary treats were a luxury for the rich. People also used sugar for therapeutic functions, with early candy serving as a form of medicine, including lozenges for coughs or digestive troubles. Sugar was also used as a preservative; similar to salt, sugar dried fruits and vegetables, preventing spoilage. But all in all, sugar was carefully conserved. In George Washington’s time, the average American consumed only 6 pounds of sugar a year (far less than the 130 or so pounds consumed annually per person today). The use of sugar swelled dramatically in 1800’s. Suddenly, sugar was everywhere, and with it came new technological advances in candy production. Sugar shipped from slave-powered plantations in the West Indies became more affordable and available with new, steam-powered industrial processes. These changes were part of the Industrial Revolution, made possible by prized whale oil and its valuable lubricating properties. In 1830, Louisiana had the largest sugar refinery in the world. The invention of the Mason jar in 1858 drove demand for sugar for canning, and in 1876, the Hawaiian Reciprocity Treaty made sugar even more available. People couldn’t get enough of sweetness. The availability of sugar brought a slew of new inventions to the culinary scene: candy! Confectioneries sprang up everywhere. The shops’ best customers were children, who spent their earnings on penny candy. Hard candies became very popular. As Yankee whaling reached its peak, Victorian-era sweets boomed with a succession of creations: the first chocolate bar was made in 1847; chewing gum followed in 1848; marshmallows were invented in 1850, and in 1880, fudge. People’s breaths were taken away when sweets with soft cream centers were tasted at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. Some candies, especially hard ones, were sold as being ‘wholesome’ and even healthy. Unfortunately, candy was anything but nourishing. Sugar was sometimes adulterated with cheaper Plaster of Paris or chalk. Other candies were far more toxic. In 1831, Dr, William O’Shaughnessy toured different confectionery shops in London and had a range of dyed candy chemically analyzed; he found a startling number of sweets colored with lead, mercury, arsenic and copper. But as ubiquitous as candy was on land, a sweet treat was quite rare at sea, especially on a whaleship. Sugar on board was a still a luxury reserved for the captain and officers. The crew had to settle for molasses, which was often infested; one whaler wrote it tasted like “tar.” Candy only makes brief glimpses in whaling logbooks, or daily records. On May 22, 1859, William Abbe journaled on the ship Atkins Adams: “Cook & Thompson Steward making molasses candy in galley.” (Earlier on the voyage, he described molasses kegs as “the haunts of the cockroach.”) Laura Jernegan, a young daughter who sailed with her father and family on a three-year whaling voyage, wrote in her diary on board the Roman, “Feb 16, 1871. It is quote pleasant today. The hens have laid 50 eggs…” Then, an exciting thing happened – she passed another whaleship at sea, the Emily Morgan. There was a whaling wife aboard, too! Laura wrote: “Mrs. Dexter [the wife of Captain Benjamin Dexter] sent Prescott [her brother] and I some candy.” In other cultures, whales still facilitated the treat scene – no sugar needed. Frozen whale blubber was (and is) a traditional treat for the Inuit and Chukchi people. Called muktuk, cubes are cut from whale skin and blubber and conventionally are served raw. While whaling in our country is a thing of the past, the years of unrestricted whaling reflect how, in essence, people treated the ocean “like a kid in a candy store,” as noted by author Robert Sullivan. In the 20th century, so many whales were caught so quickly and efficiently that soon even whalers themselves were worried about saving the whales. Today, as we continue to gather resources from the sea, we must ensure the ocean can replenish itself faster than we can sweep its candy off the shelves. Bring Candy History into Your Kitchen

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed