|

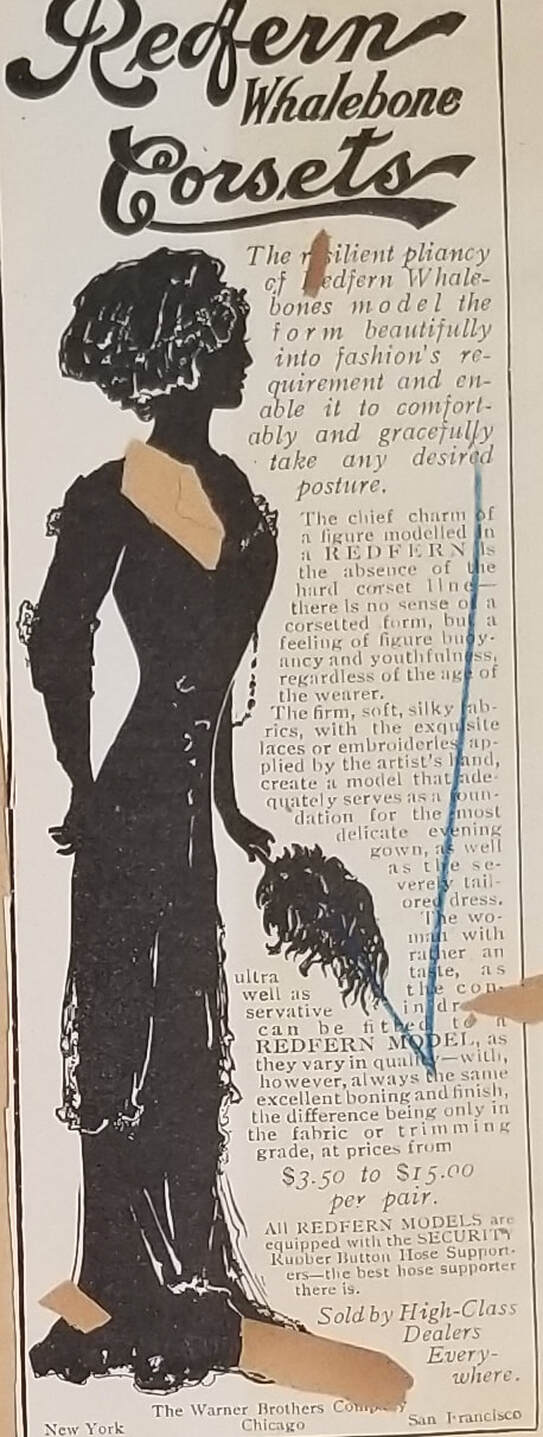

By Baylee Browning-Atkinson Special Guest Contributor Advertisements offer a glimpse of a woman's 'ideal beauty' achieved through corsetry. This young woman dips her feathered hat as she walks by. She is holding a long, wrapped package in her gloved hand. We have caught her in passing, the only clues as to where she had been are in her hands and in the shape of her waist beneath her fitted jacket. In the context of this advertisement, she could be leaving after a successful corset fitting. She walks by, satisfied with her purchase. The box in her hands contains her recently purchased Redfern Whalebone Corset. For $15.00 or less she acquired a corset of the purest Arctic whalebone, the ideal material for controlling her figure. This advertisement from the Warner Brothers Company praises the elastic and pliable qualities of the luxurious material as essential for a high end and comfortable corset. Her corset fits her as well as the gloves on her hands. She smiles and moves on. On the wrapping is stamped the praise “A WOMAN HAS・AN・AWFUL LOT・TO・THANK A・WHALE・FOR.” This source raises a very interesting question; what is this woman thanking the whale for? For what did a woman owe a whale? These four advertisements, selected from the Bridgeport History Center archive, offer some possible answers. Some of the main selling points are comfort, quality, and luxury, though there are certainly others. Do you find these points persuasive? Would your mother, grandmother, or great grandmother? The Warner Brothers Company produced and promoted whalebone corsets from 1894 until 1912. Redfern advertisements from 1894 to 1912 are rich in detail, explaining why a contemporary woman should purchase a whalebone corset for $15.00 to $3.50 over other, cheaper models boned with plant fibers, steel, feather shafts, or celluloid. At the turn of the twentieth century the necessity, purpose, and impact of corsetry was just as hotly contested then as it is today, though other garments have since replaced them. Advertisements such as the following examples contributed to the longevity of the American whaling industry by sustaining a demand for bowhead baleen in luxurious corsets at a time when the industry’s security in traditional markets, fuel and illumination for example, was threatened by cheaper and more readily available alternatives. Between the 1880s and 1910s, whalebone represented the most stable and secure market for the American whaling industry despite the rising price and unreliable quality of the material. The advertisements will help to explain why women continued to wear whalebone. This advertisement, published in Vogue in 1911 praises the quality and pliancy of the material. “You can twist, turn or bend a REDFERN CORSET in your hand, and it will spring back into its original shape, because it is boned with whalebone of the best grade, the only boning adapted to stiffening high grade corsets.” Warner’s, needing to secure high quality bone, purchased it as directly as they could without outfitting their own whalers. Redfern whalebone was purchased from New Bedford whalers returning from voyages into the Arctic grounds with holds filled with bowhead baleen. The quality of their bone, described as the “best,” “purest,” “genuine,” and “rarest” available, was a major selling point. Bowhead baleen secured from the Arctic grounds was the standard by which other whalebone was measured. The shape of a bowhead’s mouth and the length of its baleen are special adaptations to its Arctic home. The price for Arctic whalebone was typically listed as a dollar or so more on average than other types of whalebone, an indication of its commercial value. Corset companies like Warner’s used the bone as a selling point, an indication of quality, status, and luxury. Contemporary sources generally agree that it was from the bowhead whale that the most, the longest, and the finest quality whalebone available to commercial whalers and dress or corset makers was harvested. According to Warner’s advertising, these properties made it better for shaping and keeping the form desired without restricting movements or creating discomfort. The pliancy of Arctic bone was one of the Redfern’s most important selling points because pliancy implied comfort. In securing a steady supply of high quality bone, Warner’s promised a comfortable, high quality corset. Corset advertisements make it clear that a woman owed thanks to the whale for her beautiful figure. The corset, as the foundational garment beneath flowing gowns and tailored suits, was largely responsible for the fashionable fit. A woman at the turn of the century was beautiful if she had fashionable lines. Beautiful forms were smooth, symmetrical, and so aesthetically pleasing. These ideals applied to fashion, art, objects, and bodies. The idealized beauty of the nineteenth century was the Venus de Milo, however, while advertisements praise the beautiful form, their models are Parisian, not Grecian. A woman in a Redfern was beautiful because her figure was modeled by her corset “into the contour which is the mode.” The Fashionable Woman depicted here as an artist’s model is a work of art. The aesthetic design was continuously in flux, dictated by the whims of Parisian fashion couture. This advertisement, appearing in Harper’s Bazaar in 1911, credits the craftsmanship of a Redfern for giving the illusion of a natural, corsetless figure. In the absence of a hard corset line, “there is no sense of a corsetted form, but a feeling of figure buoyancy and youthfulness regardless of the age of the wearer.” The corset created the fashionable, youthful figure so sought after. All Redfern Corsets were boned with whalebone, but only those of the highest quality used imported silks, coutil, ribbons, laces, and other finery, artfully applied by Redfern designers. This attention to detail in design and material was the same paid to couture design, and gave the Redfern the status of a couture corset. “The firm, soft, silky fabrics, with the exquisite laces or embroideries applied by the artist’s hand, create a model that adequately serves as a foundation for the most delicate evening gown, as well as the severely tailored dress.” Advertisements for Warner’s Redfern Whalebone Corset promised quality, luxury materials and a comfortable, fashionable form. In essence, they promised the quality of a custom made Parisian corset at half the price. Before Warner’s could market a luxurious couture quality corset, they had to first be able to produce one affordably. As The Fashionable Woman said quite succinctly: “You may pay from Fifteen Dollars to Thirty-five dollars for a corset that is custom made - the trimming may please your eye - but the actual shaping and wearing do not compare with the Redfern Whalebone Corsets which cost from $15.00 down to $3.50 per pair.” This was accomplished through the industrialization of corset manufacture. In 1912 Warner’s stopped using whalebone. Speculation based on a knowledge of the trends of demand and supply between the whaling and corset industries leads to the conclusion that prices had gotten too high, imports too scarce, and the quality of the bone too unreliable. One of the key features of a Redfern was the quality of its whalebone. The Warner Company went to great lengths to secure their whalebone, but once the quality could no longer be reliably secured the company turned to alternative boning, likely their patented Rust-Proof Steel. Advertising played a crucial role in securing a market for whalebone by sustaining demand and generating desire for the material, for fashionable couture quality whalebone corsets, into the twentieth century. In the case of the Redfern Whalebone Corset, desire for the whalebone product was produced by an appeal to period conceptions of quality, luxury, and aesthetics. A Redfern woman was beautiful because her form conformed to Parisian models without too much undue constraint. A woman in a Redfern had the whale to thank for her beautiful, fashionable figure. Baylee recently completed her Master's in History at Stony Brook University. This blog post is adapted from a paper she completed about the mutual relationship between the American whaling and ready-made corset industries. She is a member of The Whaling Museum.

0 Comments

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed