|

Text Below for Accessibility

Between Valentine’s Day and American Heart Month, you probably have hearts on the mind this February. Check out these facts of the heart of the world's largest creature, the Blue Whale.

Read More: A Blue Whale Had His Heartbeat Taken for the First Time Ever — And Scientists Are Shocked https://www.livescience.com/first-blue-whale-heartbeat.html National Geographic: Education Blog – How Big is a Blue Whale’s Heart? https://blog.education.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/31/how-big-is-a-blue-whales-heart/

6 Comments

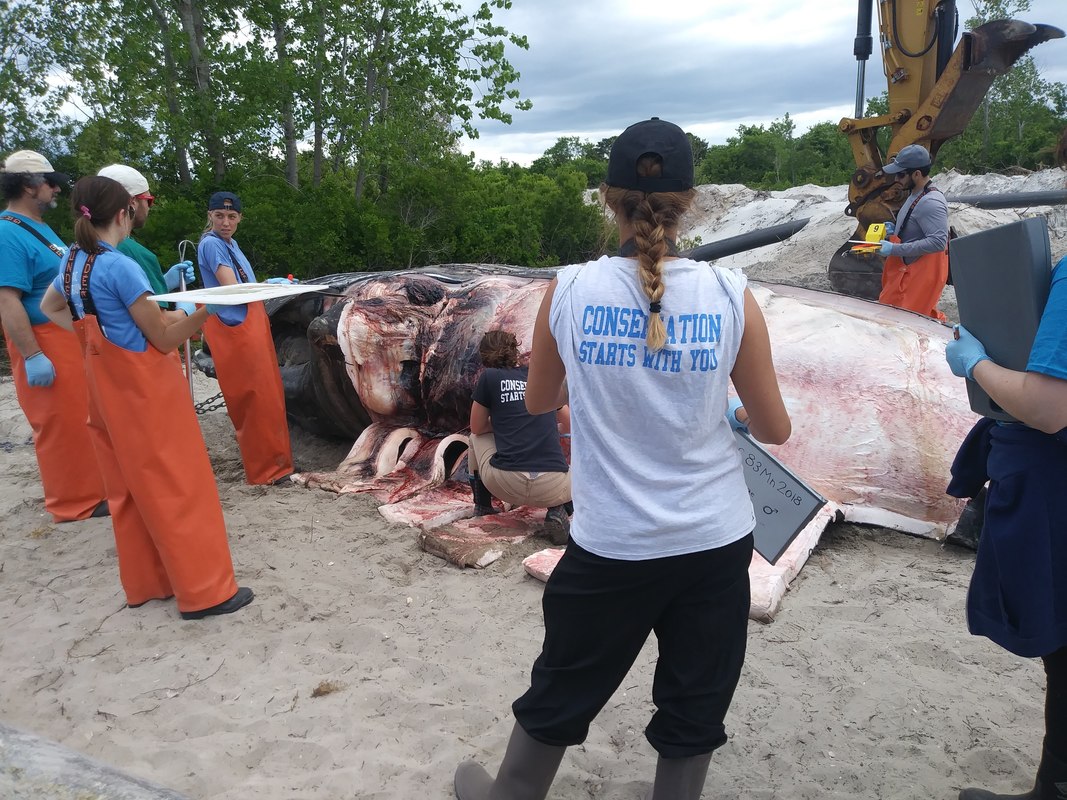

By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director at The Whaling Museum Photos taken under Research Permit AMCS #2094 When a whale beaches itself in the Long Island area, dead or alive, one man’s cell phone rings first. That man is Robert DiGiovanni. He’s the founder of the relatively new Atlantic Marine Conservation Society and its stranding response team, whose Facebook page becomes pocked with crying emojis when a dead or dying whale collapses onto the sand. I first met Rob at a beer and cheese tasting at The Whaling Museum, where he gestured to the whale models as he talked. While we chatted, he mentioned he was going to be performing a necropsy on a young Humpback whale spotted swimming the day before in Reynolds Channel in Far Rockaway. Now it was floating dead on a sandbar near Atlantic Beach Bridge - the 4th dead humpback on Long Island in less than a month. A necropsy would help explain why. My eyes lit up. A dead whale! I half-heartedly asked if he ever allowed guests to view the process. As if on cue, Ken Pritchard stepped up, sensing an opportunity. He is the museum Vice President and Commissioner of Sanitation for the Town of Hempstead, and helps oversee how the whale’s final resting place will be prepared. Ken whipped out his phone and held Google Maps open for Rob to point at. With his big fingers, Rob poked a spot off of Loop Parkway. Tomorrow morning, ten o-clock. I could barely sleep the night before. I had been teaching about whales for years, but I had never actually met one. I was like an informative field guide for a country I had not visited. Sure, I had caught breathtaking but elusive glimpses of blowholes and flukes from nauseating whale-watching trips, but everything else I knew about whales was devotedly learned from documentaries and books. I had handled whale teeth, but only after being passed through a whaler’s hands two centuries earlier. I had led kids through blubber insulation experiments, but never actually touched the real thing. What would it smell like? Feel like? Are dissections somber? What about the notorious stench I had heard about? “Boots better than shoes,” Ken texts that morning. I stare into my closet. What do you wear to a whale dissection? I decide on denim with my trusty museum uniform shirt which has the necessary whale-tail on it to help me feel official in a place where both the whale and I will be out of its element. After a short drive to Alder Island near Point Lookout, where street lights wear the spiky hats of osprey nests, Ken pulls over to a small clump of cars on a spot by the side of the highway. He wonders out loud if the car will combust from igniting the long grasses. We step out of the car, spark-free. Ironically, the area has a strong whaling history. Major Thomas Jones established a whaling station near present-day Jones beach in the early 1700’s, creating a successful monopoly around “Mereck Beach.” We search for the same goal today, a dead whale, as we venture past ubiquitous poison ivy to a random path of surprisingly soft and white sand. A Gator utility vehicle miraculously appears behind us and offers us a ride; Ken gallantly rides in the back. After a few moments of wobbling, we round a ridge of sand, and suddenly -- there it is. Before us lays a large, dead whale on its back. Its huge throat grooves are thrust up to the sky, inflated with bloat, like a giant tire half. Normally neatly pleated and only expanded to gulp water while feeding like the other great rorqual whales, the grooves are now stretched like a drum and engorged with air, deeply stippled with light and dark lines, like elevator treads. The middle of its body is centered with a small notched dimple, none other than its belly button. The whale’s notched pectoral flippers are splayed and are surprisingly long - a characteristic of humpbacks. Its genus, after all, is megaptera, meaning large wing. A humpback’s flippers are third of its body length, used to propel the whale through its herculean annual migrations, one of the longest of any mammal, not to mention spectacular aerial displays emblemized both by environmental organizations and Pacific Life Insurance. There are about ten quiet people there, most of whom are volunteers. They are wearing blue gloves and waterproof bib overalls so bright an orange that Home Depot would be proud. The backs of their t-shirts boldly state Conservation Starts With You. Supplies and a table are set up under a blue pop-up tent. Rob is there, directing volunteers how to cut into the side of the whale with machete-like flensing knives. People look dwarfed next to the whale, like fire ants cutting into the side of a large fish. I whisper to Ken, “Can I touch the whale?” “Just do it,” he hisses back. “That’ll make two of us at the museum!” The wind shifts, and suddenly we inhale the wall of stench that slams into us. We let out a choked ugh. The air reeks of rotting fish, rancid meat, and vomit. Bubbling gas is fizzing out of deliberate cuts along the whale’s side. We got it right, I think, remembering the customized scent stations we designed in the museum where visitors can smell a whaleship. I suppress a gag reflex and side up to one person. She is part of a volunteer team from Mystic Aquarium. It is a skinny male, she says, now known as AMCS83Mn2018, and is about 3-5 years old. The image of a mother and baby whale is one of the most endearing icons in nature. This whale, now a teenager, nursed from its mother for about a year, gaining several pounds a hour on toothpaste-thick milk which was 50% fat, far more than the scanty 4-5% fat in human milk. His mother would have taught him all she knew - how to communicate, how to behave, how to evade predators, preparing him for a life that should have gone to 50 years, and possibly to 100 (a century away from the 200-year longevity reported in Bowhead whales). Large, black flies are everywhere, unable to believe their compound eyes. I brush aggressive ones from my face. For them, this whale is the singles bar of the century. They are checking each other out on the whale-skin dance floor, flashing their wings, pairing up, mating, and laying their eggs. Emboldened, they start to nip at my legs. I regret not wearing pants. Another species of arthropod are also desperately clutching to the whale, simply because they have nowhere else to go. Whale lice. Thought not to be harmful, there are 29 species of these highly specialized and host-specific crabs which spend their lives tightly clutching whales’ skin folds with their claw-like legs, chewing off old skin. These lice were a gift from the whale’s own mother, who earned her lice from the mother before her. For this reason, these heirloom creatures have been helpful to scientists who use lice DNA to study whale population evolution. When a Right whale calf was found dead in 2004 with humpback-whale lice, researchers concluded that the calf was nursed by a humpback mother, if one could believe such a thing, because these lice spread through physical contact only. I peer closely at the lice, bleaching in the hot sun. They have almost no body and are all legs, dotting the dark skin like little stars, now dying as they lived. The pink ones are still alive, mourning for the untimely fate of the whale and, subsequently, their own. “You made it,” Rob says as he lumbers over, his teddy-bear frame filling his overalls. His curly hair is tufting out of the sides of his cap. Specks of shiny whale flesh are stuck to his pants. I ask if he has a hunch how the whale died. “I just focus on collecting the facts,” he answers. “Then I put all the facts together to come to a conclusion.” I inquire how long the whale is, and he states “930 centimeters,” which Ken’s phone charitably translates as 30.8 feet. Humpbacks grow to 45-50 feet, with the females stretching larger than the males. Rob goes back to calmly directing his volunteers, who are cutting sections of a rather neatly grown layer of white blubber. Blubber is not just flab. It is a unique kind of connective adipose tissue which is 60% fat, thicker and containing more blood vessels than the fat found in any other animal. Blubber is well-known for its insulating properties, but it has other functions. Blubber increases whales' buoyancy and is an important energy source for migrating whales, especially nursing mothers who fast for several months while living off of blubber for both the nourishment of themselves and their calves. The volunteers seem to be having more trouble than whalers did. “In whaler’s cases,” Rob explains, “they want the blubber. In our case, it’s in our way.” Whalers would typically use a giant blubber hook to unravel the blubber from the whale in long strips while the whale floated alongside the ship, like spiralizing the peel of a bobbing apple. Here, sections of blubber are hacked away in rectangular hunks and then peeled off to the side with hooks. The muscle underneath is light pink. “Can I help cut?” I ask, wanting the full experience. Hannah, a youthful-looking biologist for AMCS, answers in the same tone I use towards my 4 year old son when he asks to help make dinner: “These knives are really sharp,” she says, “but we can train you as a volunteer. If you give me your contact information, I can send you information.” I must look crestfallen, because she explains, “Look, I once almost sliced my finger off. It didn’t heal quite straight, but...” She holds her index finger up, wiggling its angled fingertip. I smile politely. I grab a pair of gloves and approach a cast-off piece of blubber. Surprisingly, it is simultaneously firm yet gummy, with a gelatinous surface which jiggles when I vibrate my finger. The surface sticks to my glove like silly-putty. Phew, I thought. When we have kids make goop at the museum and we tell them it’s whale blubber, we are not that far off. “Get a new knife,” I hear Rob instructing. “I just switched knives, and it cut into it like butter.” I am surprised how they face the same troubles as whalers on a whaleship, who would call out “another sharp one!” to a blacksmith or barrelmaker who would constantly sharpen spades for the crew during the blubber-stripping process. I walk around the whale’s body, respectfully quiet. I pass its eye. Its eyelid is partially open. Many people have shared that when you look into the eye of a whale, the experience is profound, even spiritual. When I met the gaze of a dolphin swimming sideways to look back at me on one whale watching trip, the feeling was transcendent. There is something there – a human-like consciousness perhaps - looking, feeling, and thinking back at you. And here, even dead and rotting on the beach, there was still something there behind that eye. As if on cue, Rob comes over. He plunges his knife into the side of the eye. Dark, thick juices hiss out, and – ploink! – out comes the eyeball. I swallow hard. “Left eyeball!” he calls out. A volunteer dutifully stumbles over the sand with a cutting tray, and like a good waiter, delivers the wobbling sphere back to the tent. I kneel by the whale’s face. Ken snaps a picture, cheering “Our fearless director!” The skin around its snout is mottled gray and white, with rounded tubercules protruding around the snout, like bumps on a pickle. To my astonishment, the biology books hold true: there, in the center of each tubercule, is one single, tiny, yellow hair. The single bristle feels stiff when I poke it with my finger. This tiny thorn is the very last speck of thousands of years of the evolutionarily shedding of whale fur, one hair at a time, a firm no-thanks to the stubbly genes that bind us bristly mammals. I now touch its skin. The surface feels like tire rubber. I move on to touch the bristles of baleen on its upper jaw. The baleen is a messy, interweaving network of keratinous fringe, thick and matted like a bird’s nest. The bristles feel like a tough broom. While I had taught for years how baleen filters food out of the water, I now fully understand how tiny shrimp are truly entangled and then swallowed. The smell is intensifying. The elation I expected to feel upon completing a highlight of my life – to touch a whale! - is being drowned out by the sick miasma pouring out. I continue to take shallow breaths and chew mint gum. I look over my shoulder and see Ken is smartly upwind. With the hot sun baking overhead, and bacteria reproducing by the trillions beneath the blubber, methane is building up, producing one of the worst smells nature has ever produced. This is what made whaleships the stinking rose of the nautical world, with ships downwind able to smell a whaleship before seeing one. Nauseous, choking smells were one of the top complaints of life on a whaleship. One seaman wrote in 1860: “It is as if the ill odors of the world were gathered together and being shaken up.” Whaler Charles Nordhoff described verbosely how one could not get away from the oily stench in 1856: "Everything is drenched with oil. Shirts and trowsers are dripping with the loathsome stuff. The pores of the skin seem to be filled with it. Feet, hands and hair, all are full. The biscuit you eat glistens with oil, and tastes as though just out of the blubber room. The knife with which you cut your meat leaves upon the morsel, which nearly chokes you as you reluctantly swallow it, plain traces of the abominable blubber. Every few minutes it becomes necessary to work at something on the lee side of the vessel, and while there you are compelled to breath in the fetid smoke of the scrap fires, until you feel as though filth had struck into your blood, and suffused every vein in your body. From this smell and taste of blubber, raw, boiling and burning, there is no relief or place of refuge." Suddenly a woman who looks vaguely familiar announces, “We have some bruising!” Dark hemorrhaging has spread around the area behind the flipper, as if someone spilled a giant bottle of crimson ink, possibly indicating a vessel strike. More pictures and samples are taken. Then she asks, “Who here has clean hands?” Just one volunteer raises a hand. “Can you lift my sunglasses and put them on my cap?” she asks, and finds something to wipe the sweat off her face. She is wearing a psychedelic-colored cap with the word Joy written on a green piece of masking tape fixed to the front side. Now I remember: I had met her from my couch as I watched her on PBS, dumbfounded as she explained how our vocal cords evolved from fish gills. She is Dr. Joy Reidenberg, a research scientist who specializes in comparative anatomy. Today, she is here as a volunteer. Her dark ponytail, streaked with silver, sticks out of the back of her cap. At one point she hollers loudly, “Did you do the genitals?” in the same tone one would ask a friend where they parked the car. Unlike other mammals, whales have elected to keep their procreative organs demurely hidden. All rules are off during mating season. Male Southern Right whales take the gold for the most highly endowed animal, whose prehensile-like phallus reaches an unprecedented 12 feet, helpful in breeding showdowns. Smartly, veins of cooled blood returning from the flukes are routed to the testes to keep sperm production chilled. Not to be undone, female reproductive gear is quite complex with a dizzying number of species-specific twists, turns, and angles that are still poorly understood. Still unwilling to sacrifice even an inch from being thoroughly streamlined, alongside each side of the female’s genital slit are two nipples, inverted when not actively nursing. Each can actually eject milk right into calves’ mouths in a thick, fatty, ribbon-like stream, helpful since calves can’t really move their lips.

I ask Joy a very important question: “How do you deal with the smell?” “What smell?” she answers incredulously. “This is nothing like dead sea turtle. That is bad. This is fresh! Fresh meat!” I gently place her sunglasses back on her face for her. While I try to conceptualize a smell worse than the one we are breathing in, Rob calls out helpfully, “I breathe through my mouth!” It has been a few hours now. Ken patiently waits, father-like, telling me, “When you’re done learning, you let me know. I’m checking emails,” - and to reassure me of his hard work - “See, I just disciplined someone!” Two members of the Coast Guard come to stare with appropriate disgust. Bottled water is passed out. I reflect on the irony of us drinking from single-use plastic bottles which are undisputedly choking the ocean while we examine this whale for evidence of human impact. I look at the whale’s tail in the sand, which feels surprisingly firm and stiff. There are no bones in whales’ tails; instead the flukes are made up of muscle and dense tissue. Besides for being used to propel a whale through the water, tails are used for lobtailing or tail slapping, thought to be a form of communication as well as defense. Arteries and veins in flukes help maintain the whale’s temperature. Southern Right Whales even use their flukes like sails: they lift their flukes into the wind to move through the water. Researchers rely on the color patterns, shapes, and scars on whale tails to aid with identification, just like human fingerprints. In the past few years, there has been a disturbing uptick in the number of sightings of Humpback and Gray whales who have lost this most quintessential part of their biology. Likely choked off by entangled fishing line, a consequence of industrial fishing which occupies a third of the planet, the majority of tailless whales are thought to eventually succumb to this fatal handicap. Astonishingly, there have been reports of plucky individuals who continue to survive, even on unimaginable migrations. The excavator is now called into service. We stand a respectable distance back. Flashes of YouTube videos showing whale carcasses exploding like geysers run through my mind. With directional waves of Rob’s hands, the pectoral fins are detached from their white sockets. The backhoe raises its giant metal jaws, like a T-rex above a kill, and starts to peel back the lower jaw. We hear a popping sound of released gas. “There it goes,” Ken says. “Try not to cut the larynx!” Joy calls. Ken watches the backhoe carefully. “He’s good,” he evaluates the operator. As the jaw is lifted, Ken calls out, “If the jaw swings, won’t it hit the tent?” “No!” Rob hollers back reassuringly. “It would hit me!” Rob and Joy continue to cut alongside the whale, slicing through tendons and muscles as the backhoe continues to peel the whale apart, helping the whale to split. The massive, cushiony gray tongue spills out of its mouth, like overturned dark Jello. Rob explains that the tongue itself can weigh over a ton. Dark rivulets stream out from under the whale and pool in the sand. “Do whales have taste buds?” I wonder out loud. “There’s evidence for taste buds in some dolphins,” Rob answers. Salt seems to be whales’ primary taste; the other taste buds have atrophied away. While this sounds like a pitiful way to eat, no whale chews its food, so they likely don’t care too much about what they’re missing. Whale tongues are a prized delicacy for orca whales, who will viciously attack whales in teams and then feast on the tongue first. There is even a mutualistic story of a pod of killer whales who teamed with whalers near Australia bring down whales for a chance to eat the tongue. The upper jaw is cast to the side. “Wouldn’t you like that?” Ken whispers about the fringed baleen. “For the museum? Imagine he says you can have it. Now what do you do with it?” Not only would I have to figure out what to do with half a whale head, but I have to figure out what to do with the whale palate in the museum that I now realize is ceremoniously displayed upside down. Who would have thought the center of a whale’s palate grooved inward at its center, and was not domed upwards like ours? I then notice something oddly strange taking place. I blink my eyes. The cut pieces of whale are a sickly green. They weren’t green a few minutes ago. Is it my imagination? Am I being blinded by the sun? Joy explains, “It’s exposed to oxygen, and it’s rotting.” Now I see why whalers truly had to process whales immediately, even – to the dismay of whaling wives – on the Sabbath. Because of the insulating properties of blubber, whale flesh decays extremely rapidly. Joy now steps into the spilled organs of the whale. Her boots disappear into swirled guts. Volunteers pull their shirt collars up over their faces to block the stench. Ken takes a look, proclaims “Disgusting!” and walks back to the side. A volunteer is behind her, ready to catch her if she starts to slip. She reaches within the spinal cord, trying to feel for the brain. “Nothing!” she says. Just recently dead, and the brain has already decayed into liquid. They are examining the lungs and the stomach, which sadly turns up empty instead of full of bunker, the fish that is drawing more and more Humpbacks to the area. I want to stay and see the rest of the organs, but I surrender to my own mammalian need to pump milk for my own little human calf at home, who is wearing a onesie with a smiling whale on it. Ken leaves instruction not to dig the ten-foot deep hole for the whale until the entire necropsy is complete. Burial is the most natural and practical way to let nature take care of the whale. We leave as the lower intestines are spilling out, which are cream-yellow and kinked like giant sausage. When we get back into the car, we wrinkle our noses. “Ken -- do we smell?” I innocently ask. Because the odors are oil-based, the smell is slow to dissipate. If only we knew that ten minutes later, his typically reverent employees would be vocally throwing him out of the office, demanding he take a shower before returning. I finally drive myself home with both the AC on high and each window fully down, barely able to stand myself. I need to make a stop at a store, but decide I’m not fit to be around people. If we had only observed the necropsy and smell like death, my eyes cross to think how bad the people actually performing the task smell - and how bad whalers themselves smelled, who could not decently wash for years. I feel refreshed after a hot shower. My husband complains the bathroom still smells, and silently banishes my sneakers to the front porch. At the end of the day, I check the AMSC’s Facebook feed: "The necropsy examination showed that the whale had not been actively eating and may have been sick. Samples are being sent to a pathologist to help determine a cause of death, and results may take several months to come back." I look at the posted picture of the whale before the necropsy started. My eyes now see a complex machine through the tough skin - tendons, muscles, blood, innards. Three days later, Ken texts, “My car still smells, slightly.” My shoes are still cast outside of the house, forlorn. Ken adds, “I’m going with the story that you stunk worse than I did. I spent a large amount of time upwind.” I try to relate the greatness of the necropsy to my wincing museum team - “the blubber! the stink!” - as they cover their noses in empathy. My mother texts please don’t send any more pictures. My sister says I’m throwing up just thinking about it. But I remember what Long Island ornithologist and museum founder Robert Cushman Murphy wrote in his diary on October 10, 1912 when he observed his first whalehunt: “This has been the most exciting day of my life.” While I observed no hunt and only whale, I know he’s not making it up. What do I do if I see a whale on Long Island?

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed