|

By Nomi Dayan Have you ever been asked to please stand by? Ever told someone not to barge in? Have you hung on to the bitter end, or been given a clean bill of health? If so, you have spoken like a sailor. Each type of human activity, noted essayist L. Pearsall Smith, has its own vocabulary. Perhaps this is most evident in the speech of mariners. The English language is a strong testament to how humans have been seafarers for millennia, with a multitude of words and phrases having filtered from life at sea to life on land. Today, a surprising number of phrases, words, and expressions still have nautical origins, notably from sailing terminology in the 18th and 19th centuries. While some adopted phrases have fallen by the wayside, many expressions in our everyday language are derived from seafaring. Barge in: Referring to flat-bottomed workboats which were awkward to control

Bitter End: The last part of a rope attached to a vessel Clean Bill of Health: A document certifying a vessel has been inspected and was free from infection Dead in the Water: A sailing ship that has stopped moving Down the Hatch: A transport term for lowering cargo into the hatch and below deck Figurehead: A carved ornamental figure affixed to the front of a ship Foul up: To entangle the line Fudge the Books: While the origins of this term is unclear, one theory connects it a deceitful Captain Fudge (17th century) Give Leeway: To allow extra room for sideways drift of a ship to leeward of the desired course High and Dry: A beached ship Jury Rig: Makeshift or temporary repairs using available material Keel over: To capsize, exposing the ship’s keel Show the ropes: Train a newcomer in the use of ropes on sailing vessel Letting the Cat out of the bag: One explanation links this phrase to one form of naval punishment where the offender was whipped with a "cat o' nine tails," normally kept in a bag Passed with flying colors / Show One’s True Colors: Refers to identifying flags and pennants of sailing ships Pipe Down: Using the boatswain’s pipe signaling the crew to retire below deck A New Slant: A sailor will put a new slant on things by reducing sails to achieve an optimum angle of heel to avoid the boat from being pulled over Slush fund: The ship's cook created a private money reserve by hoarding bits of grease into a slush fund sold to candle makers Steer Clear: Avoid obstacles at sea Taken Aback: Sails pressed back into the mast from a sudden change of wind, stopping forward motion The author is the Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor.

0 Comments

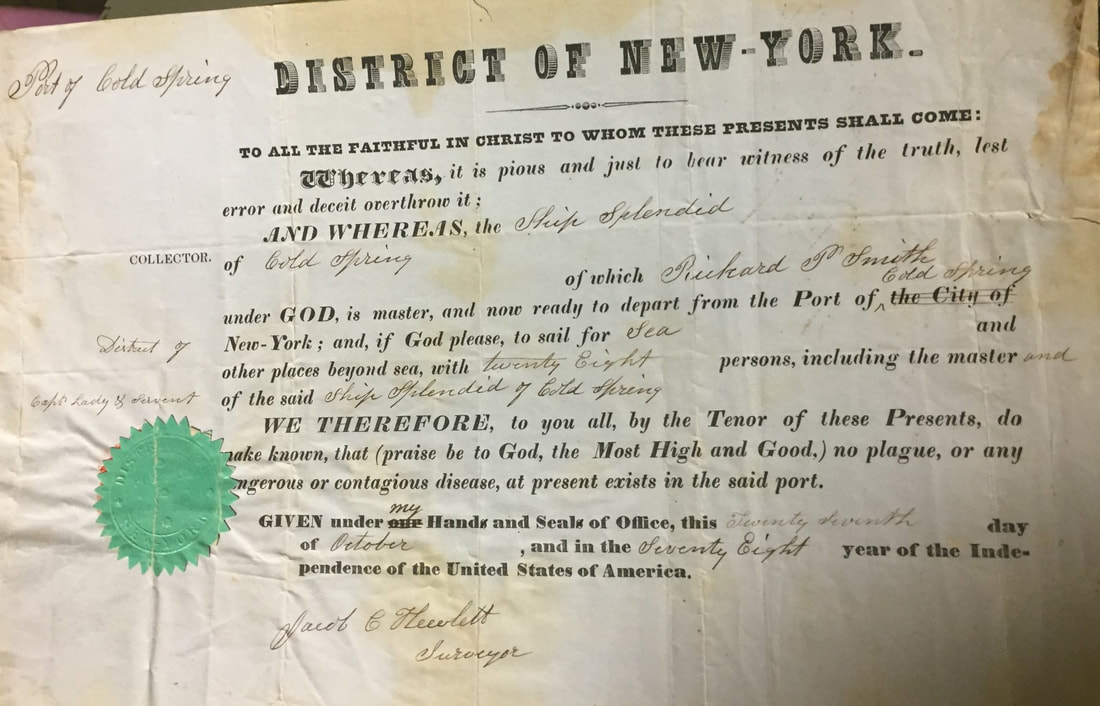

Turn of the century glass plate portrait of mother and infant in Australia. Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Turn of the century glass plate portrait of mother and infant in Australia. Courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. By Nomi Dayan As I prepare to become a mother for the third time around, I am brought to reflect on one of the most dirty, reeking, and unlikely places to possible to birth a baby: a whaleship. Today’s challenges with pregnancy and childbirth pale in comparison with the experience of the 19th century woman – and even more so, the challenge whaling wives faced at sea. Because whaling wives saw so very little of their husbands, some resorted to going out to sea – a privilege reserved for the wife of the captain. Aside from dealing with cramped and filthy conditions, poor diets, isolation, and sickness, many wives eventually found themselves – or even started out - “in circumstance.” In the 19th century, pregnancy was never mentioned outright. Even in their private diaries, whaling wives rarely hinted to their pregnancies. Some miserably record an increase in seasickness. Only the very bold dared to delicately remark on the creation of pregnancy clothes. Adra Ashely of the Reindeer wrote to a friend in 1860, “I am spending most of my time mending – I want to say what it was, but how can I! How dare I!” Martha Brown of Orient was more forward by mentioning in her diary in 1848 that she is “fixing an old dress into a loose dress,” with “loose” meaning “maternity.” Once the time of birth approached, women at sea faced two options: to be left on land – often while the crew continued on - or to give birth on board. Giving birth on land was far preferable, as the mother would be theoretically closer to medical care and whatever social support was available. Martha Brown was left in Honolulu – much to her personal dismay to see her husband depart for 7 months – but fell into a supportive society of women, most left themselves in similar situations. During Martha’s “confinement” after birth when she was restricted to bedrest, a fellow whaling wife nursed her. When Captain Brown returned, he wrote to his brother: “Oahu. I arrived here and to my joy found my wife enjoying excellent health with as pretty a little son as eyes need to look upon. A perfect image of his father of course – blue eyes and light hair, prominent forehead and filled with expression.” Giving birth on land did not always ensure a hygienic setting as one would hope. Abbie Dexter Hicks of Westport accompanied her husband Edward on the Mermaid, sailing out in 1873. Her diary entry on the Seychelle Islands was: “Baby born about 12 – caught two rats.” Some whaleships found reaching a port before birth tricky. In 1874, Thomas Wilson’s wife Rhoda of the James Arnold of New Bedford was about to give birth, but when the ship arrived at the Bay of Islands of New Zealand, there was no doctor in town. A separate boat was sent to search up the Kawakawa River for 14 miles; when a doctor was finally found and retrieved, the captain informed the doctor that it was a girl. Some babies were born aboard whaleships – either by design or by accident, despite hardly ideal conditions. Births, if were recorded in the ship’s logbook, were mentioned matter-of-factly. Charles Robbins of the Thomas Pope was recorded in April 1862: “Looking for whales… reduced sail to double reef topsails at 9pm. Mrs. Robbins gave birth of a Daughter and doing nicely. Latter part fresh breezes and squally. At 11am took in the mainsail.” Captain Charles Nicholls was in for a surprise when he headed to New Zealand on the Sea Gull in 1853 with his wife. Before the birth, fellow Captain Peter Smith had told him during a gam (social visit at sea), “Tis easy,” and advised the first mate be ready to take over holding the baby once it was born. When the time came, Captain Nicholls dutifully handed the baby to the first mate, only to return several minutes later shouting, “My God! Get the second mate, fast!” – upon when he promptly handed out a second infant. Captain Parker Hempstead Smith’s wife went into labor unexpectedly: “Last night we had an addition to our ship’s company,” seaman John States recorded on February 18, 1846 on board the Nantasket of New London, “for at 9pm, Mrs. Smith was safely delivered of a fine boy whose weight is eight lbs. This is quite a rare thing at sea, but fortunately no accident happened. Had anything occurred, there would have been no remedy and we should have had to deplore the loss of a fine good hearted woman.” He also added his good wishes for the baby: “Success to him – may he live to be a good whaleman – though that would make him a great rascal.” The author is the Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ More Reading: Druett, Joan. Petticoat Whalers. Auckland: Collins, 1991 MacKay, Anne ed. She Went a Whaling: The Nournal of Martha Smith Brewer Brown. Oysterponds Historical Society, 1993  This 1836 Leather-bound journal of Captain Richard S. Topping of the Bark Monmouth is just one of the artifacts to be digitized with this grant. This 1836 Leather-bound journal of Captain Richard S. Topping of the Bark Monmouth is just one of the artifacts to be digitized with this grant. After 81 years in the dark, The Whaling Museum & Education Center will be shining some light on its hidden collection through a generous grant from the National Park Service’s Maritime Heritage Grant Program. Part of a 1:1 match of $49,557, this funding will allow the museum to digitize, preserve, and create publicly available online access to an estimated 2500 items selected from its permanent collection. The considerable project, scheduled to be completed by 2019, will dramatically increase access to the museum’s significant and historical collections by producing publicly accessible digital archives, and will enhance public awareness and appreciation for the key role whaling played in our country’s maritime heritage. As part of the project, the museum will also produce object-based curricula and teaching materials for schools which highlight using the online collection in classrooms. An essential component of this project will be digitizing the museum’s archives, a largely untapped and unknown resource which offer perspectives, insights, and research opportunities not found in any other museum. This includes 95% of the existing manuscript material from the Cold Spring Harbor whaling fleet, records of the Long Island coastwise trade under sail, crew lists, shipping papers, prints, photographs, and correspondence. Together, these archives form a rich visual record of Long Island’s development as a historically prominent whaling center. Executive Director Nomi Dayan explains, “We are honored and excited to be one of three New York organizations successfully awarded this year by the National Maritime Heritage Program. When visitors view our exhibits, most don’t realize that what they’re seeing is the tip of an iceberg, as approximately 5% of our collection is on view at one time. This project helps us extend past restricted physical space and enhances our institutional capacity to both preserve the collection through digitization, as well as better serve the public by making largely unknown resources publicly available online. Ultimately, we hope this project will engage the public in ongoing conversations about the social, cultural, political, economic, and environmental forces of our whaling heritage that have shaped our country.” Dayan added, “This project will also open the museum’s doors to a global audience. In the past few months, we have received research inquiries from individuals from Australia to Chile. This project will radically enhance access without having to rely on staff time or necessitate travel to the museum.” Currently, the only way browse the collection is to physically cruise the tightly packed drawers, folders, and boxes in storage, which is inefficient and compromises the items’ fragility. Online access with a searchable database is a vital tool for promoting public appreciation and understanding of history – and in the case of whaling history, connecting the processes, events, and interactions among people and whales to scientific and cultural understanding today. “This is a very exciting time for the museum's collections, says Collections and Exhibitions Manager Kyrsten Polanish, “This project will help to prolong the life the objects by reducing the amount of times objects are physically handled while making them more accessible to anyone wanting to find out more about maritime history.” Improved cataloging, digitization, preservation, and documentation for the artifacts would elevate the museum’s archives to the current best practices of collections management. The museum’s archives are currently available for research by appointment only.

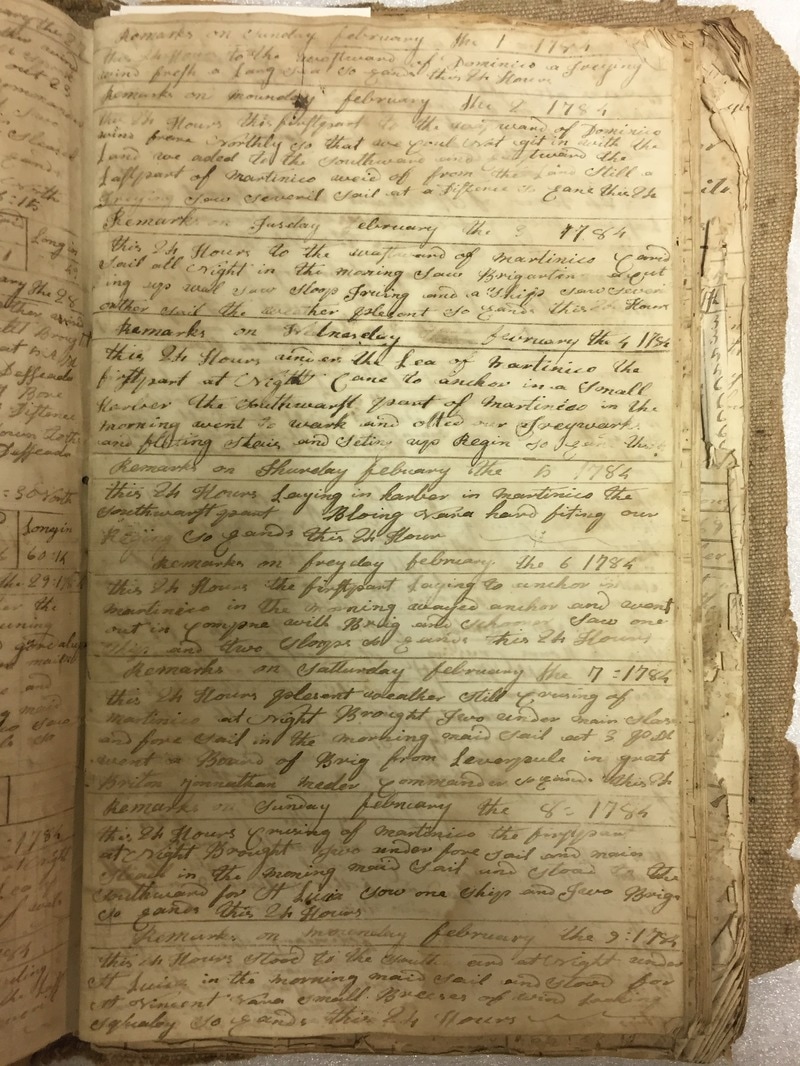

By Kyrsten Polanish, Collections & Exhibits Coordinator When you work in a collections position, conducting inventories comes with the job. But by no means are these inventories boring! Through these routine inventories, you often have the opportunity to find interesting artifacts buried in storage, possibly ones previously thought to have been lost, or notice some new detail of a piece that brings further enlightenment to its historical value and nature. The most recent inventory I have been conducting is of our Logbook collection. Logbooks are the official records kept on board a ship often by the first mate or another high ranking officer. These keepers write down the major events that occur on ship, weather patterns, coordinates of the ship’s location and, in the case of whale ships, records of where whales were spotted and how many barrels of oil were brought in. Our Logbook collection is not that large as compared to some bigger institutions so when seven logbooks were not able to be located in the process of the inventory this was puzzling. After having attacked this dilemma from multiple angles and looking in every drawer and box possible, I was ready to put this aside to come back to later with fresh eyes, when a research request came in. This researcher just so happened to be looking for information out of two of the “missing” logbooks. Thus, this request forced me to keep pushing forward posthaste. Where did this eventually lead me? To 45 years of paperwork and a seemingly less than ordinary looking book. I came up with the idea of trying to find the original donation documents which meant sorting through those 45 years worth of collections paperwork. The time was well spent, however, when I found the original documents which completely solved the mystery, all thanks to the description contained within. That description indicated that a burlap covered book, that had always remained a bit of a mystery, was indeed a logbook. On top of that, it did not just have one logbook within its binding, but seven! Considering all other logbooks in our collection had one voyage in one book, this detail was extremely odd to us. We couldn’t quite figure out why this would be. Honestly, we still don’t. The running theory is that the unknown record keeper was the same person for all seven voyages within the book and that this man simply kept carrying around the same book out of convenience or financial necessity (paper was not cheap back then). Was I able to finally finish the logbook inventory and account for everything? Yes! Will we ever know why this book has seven voyages? I don’t know, but I hope so. For now, it will continue to be a mystery waiting to be solved. For years, the Museum's "pay as you wish" hour took place on Sunday mornings from 10-11am. The only problem was that not very many people took advantage of that hour, surprisingly. Our staff felt the offer ultimately did not boost visitation, even though we intended to make sure there were no economic barriers to museum visitation.

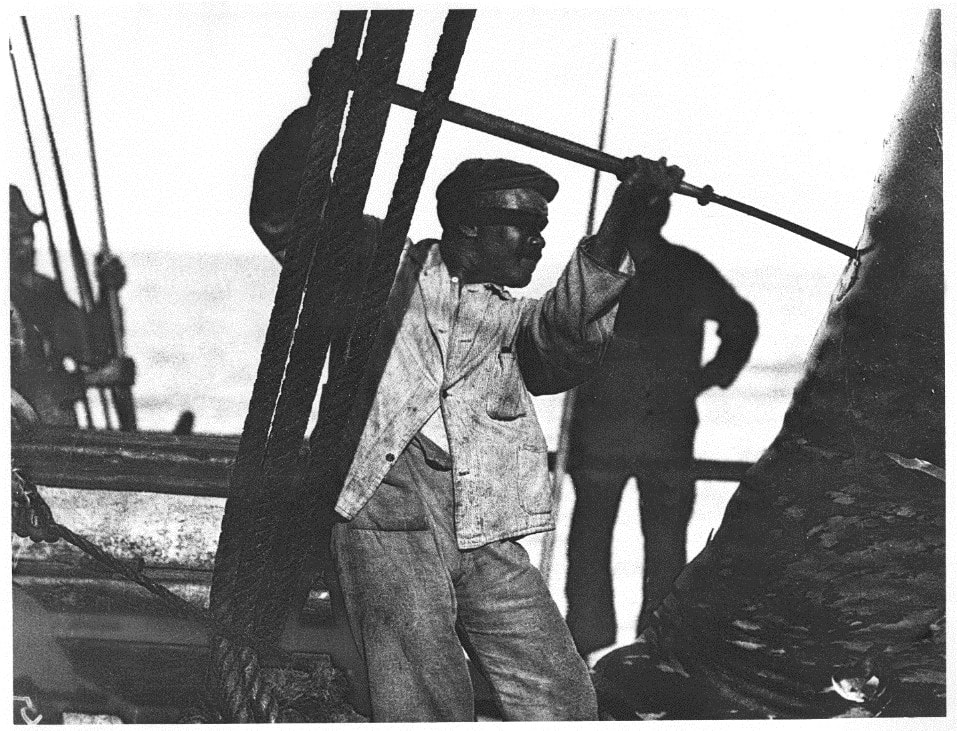

This summer, we're changing things up to try to encourage more Long Islanders to visit. From July through August, our galleries will be staying open late from 5-7pm, with admission by donation. We hope both Long Islanders and visitors will make the time to visit to explore one of the most amazing phases in Long Island history. In non-summer months, the museum will also offer a pay-as-you-wish day on the first Wednesday of the month from 12-4pm. Will our experiment of "Welcome Wednesdays" work? We'll see - - and we hope to see you there!  Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor joined her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. Courtesy Audrey Hank Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor joined her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. Courtesy Audrey Hank Recalling The Woman’s Experience on Whaleships In Honor of Women’s History Month By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center, Cold Spring Harbor “It is no place for a woman,” wrote Captain James Haviland on the Baltic in 1856, “on board of a whaleship.” The long saga of hunting whales, one of Long Island’s most historically prominent industries, was unquestionably viewed as man’s world. Whalers were exclusively male, and their lives were fraught with dangers and hardships, cramped and filthy living conditions, rowdy company, monotonous life, and risky circumstances. No wonder Irish traveler John Ross Browne wrote in 1846, “There is no class of men in the world who are so unfairly dealt with, so oppressed, so degraded, as the seamen who man the vessels engaged in the American whale fishery.” These conditions did not extend into the prescribed separate domestic sphere of “the fair sex.” The 19th century saw sharp gender roles for men and women, and Ladies were supposed to be pious, graceful, passive, pure, and focused on children and homemaking. The male-dominated industry relied on family members to manage life ashore during their long absences, which could extend three to four years. Women who remained home suddenly found themselves as lone masters of their households. They maintained their families as single parents, took care of elderly parents, paid the bills (or lived on credit), tended to any farming, and waited with wifely devotion. To help make money during their husbands’ absence, some women became entrepreneurs, running inns, becoming teachers, or serving as midwives. Women also formed deep relationships within their own female society, using a network of communal support to fill the void created by their temporary abandonment. The life of a whaling wife was undoubtedly a lonely one, almost like that of a widow. She would ache for the day her husband would retire. But as time went on, some women found themselves incapable of enduring the separation anymore, and a number of captain’s wives broke boundaries by deciding to do what no woman had done before: join their husbands at sea. One can understand their impetus when looking at Azubah Cash of Nantucket. She had been with her husband for half a year out of 11-year marriage, spurring her to sail with him on his next voyage. More often than not, these wives were not renegades and rebels. They simply preferred the discomforts of life at sea to years of separation at home, defying convention which placed the woman’s role in the home, and became trailblazers by necessity. In the early 19th century, whaling wives were rare, as such behavior was unladylike. But as the industry boomed in numbers – and voyages grew in length of years - an increasing number of women made the decision to endure long and difficult years at sea, either with or without their children, showing remarkable endurance and courage. By the 1850’s, one out of six whaleships carried the captain’s wife aboard. These vessels were nicknamed “hen frigates.” A whaling wife on board would still spend her time waiting - not for her husband’s return, but instead for the ship to fill up with oil. She would not take part in the whaling process, other than casually spotting a whale; instead she would fill her days educating her children, reading, washing clothes, sewing, writing in her diary, and cross-stitching while confined in cramped quarters to pass the long hours. While a separate cook was hired to oversee meals for the crew, she may have prepared special treats. Some wives learned how to navigate, including Maria Cartwright Baldwin of Shelter Island, who learned to take the helm. Others made efforts to bring religion to the crew. The crew were commonly pleased to have a woman aboard. Wives often served as nurses, a valuable role in a place where sickness and injury, some severe, were common. Women also had a calming effect on the seagoing male society; their presence made it more likely holidays would be observed, and if the captain punished a crew member, he might do so less harshly. Children could be also be a welcome distraction from the flat monotony of life at sea. However, there were instances where crew members did show frustration and resentment when family life inevitably disturbed what financially mattered – catching as many whales as possible in the shortest amount of time possible. Once whaling wives were socially accepted, captains often celebrated their companionship and closeness. Captain Henry Gardiner of Quogue missed his wife Polly so much that he often doodled her name in the margins of the ship’s logbook, or daily record. She joined him on the next voyage, where she cross-stitched a sampler which is currently on view at the Whaling Museum in Cold Spring Harbor, which she dated, “Bound to the Pacific Ocean in the ship Dawn. March 16, 1828.” Whaling wives’ diaries are powerful testaments to the hardships they endured, including illness, boredom, violent seasickness, powerful storms, dangerous whaling grounds, frightening mutinies, and death. Conditions at sea left much to be desired, with rampant fleas, roaches, and rodents. Sarah Eliza Jennings of Sag Harbor was aboard the Mary Gardiner which was chased by a Confederate raider, a frightening ordeal, and Elizabeth White of Cold Spring Harbor was aboard the Courser when it was rammed by a steamship and sunk off the coast of Chile in 1873. Several Long Island whaleships were caught in an early Arctic freeze in 1871, and wives and their children escaped onto the ice with the crew (all were rescued). Whaling wives’ diaries also reflect the excitement of the rare chance to socialize with women who happened to be passing by on other whaleships, an experience called gamming. The opportunity was a chance to catch up on news and fill the tremendous void of social contact. Even with their husbands at sea, seagoing wives - known for their propriety - faced social isolation as the only woman on board. When seagoing wife Eliza William’s brother in law was asked what her success at sea could be attributed to, he replied “always minding her own business.” When wives found themselves “in circumstance,” they were often conveniently deposited in Hawaii for several months while the crew continued on. Interestingly, a society of whaling wives grew there, forming a social network and domestic circle. They helped each other with births, circulated crochet patterns, and shared each other’s company. Martha S. Brewer Brown (1821-1911) of Oysterponds spent time in Hawaii. After the agonizing choice to leave her two-year-old daughter with relatives, she sailed with her husband, Edwin Peter Brown, who was one of Long Island’s most successful whaling captains of all time: on one voyage, he filled his ship with 1,500 barrels of oil in 363 days, circling the globe without dropping anchor and setting a world record. Martha unhappy and resentful at being left in Hawaii to give birth. “My husband left me in one of the most unpleasant situation a Lady can be left in, without her husband, among strangers, with the request that I would do my [clothes] washing myself – a thing which no other American Lady does, not even the mission Ladies,” she wrote in her diary. She forbade her husband to leave her for whaling again, but he did. Eliza Edwards of Sag Harbor was another brave soul to join her husband, Captain Eli H. Edwards, at sea in 1857. She too lived in Hawaii for a time, becoming close friends with other women there, while the crew continued on to the Okhotsk Sea. Her letters expound on Hawaiian life at the time and are in Mystic Seaport Museum’s collection. Some mothers raised their children at sea for prolonged periods of time. Caroline Rose (the “Belle of Southampton”) sailed with her husband, Captain Jetur Rose, for 15 years. One cabin boy called the couple “the finest people he had ever met.” Caroline gave birth to her only child, Emma, in Honolulu in 1856, who was raised at sea. Emma logged thousands of miles before her 13th birthday. When a missionary came on board to try to educate Emma, claiming “no one on a whaler knew anything,” Emma stated, “I know the Ten Commandments and multiplication table, and that is enough for any little girl to know.” Mothers certainly had to deal with the ordeal of children falling sick at sea. Elizabeth Jones of Setauket on the Tri-Mountain cared for five children who came down with measles at sea, all at the same time (all the children recovered). Aside from whaling wives, other “sister sailors” joined their husbands at sea on coastal traders, such as Mary Satterly of Setauket, who spent her 24-year marriage at sea with her husband, Captain Henry Rowland, starting in 1852. Compared to other regions, whaling wives from Long Island were relatively infrequent because the wife-travelling trend was not synced with the area’s earlier decrease of local whaling companies. But even when women were not physically present on whaleships, their presence remained ubiquitous in another way. To fill idle hours at sea, whalers carefully carved scrimshaw, painstakingly etching images on whale teeth and bones. One of the most widespread themes is a fancy, beautifully dressed woman. Some pieces depict sweethearts or female relatives; others were copied out of advertisements; others were dreamy, classy, high-society fantasies conjured by men who had not seen a woman in months (as well as not having bathed in months). It is a treat today to be able to gaze at these women, who stare back at us from the surface of a tooth. Frozen in their cold medium of bone, they challenge us to rethink our own assumptions today: is there a ship would we rather be on? On View at the Museum in March:

More Reading:

Old Museum, New Audience - Great Blog!By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director

When I first joined the Whaling Museum, I remember thinking: am I going to be stuck teaching about dead whales every day? ... I had up until then worked in institutions with live animal exhibits. The answer? No, it has not! But it didn't just happen that way. Our museum made a strategic, deliberate choice to go beyond the subject of whaling. It has been a wild ride! Our museum has a new title, new mission, new logo, new website, not to mention new events. And for good reason, too, because we do not exist to only talk about what happened yesterday. We want to talk about what's happening today and tomorrow. We want to talk about why our whaling history matters. We're nearly 80 years old. Why have a whaling museum anyway? Yes, whaling happened here, and it was important at the time. But that's not why we exist. We are here to help the visitor to understand our whaling past as part of a larger story, with lessons that matter today. This blog, "Thar She Grows," will highlight and celebrate a small maritime museum's journey to keep up with the pace of the world around us, in a time when building attendance at history-based organizations is dropping. Follow our ideas, celebrate our achievements, and offer suggestions to our challenges! Welcome aboard! |

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed