|

By Baylee Browning Collections and Exhibits Associate The museum recently received a clay pipe with a special connection to the Cold Spring Harbor community. Nan R, who donated the pipe, shared her story about how it was discovered: "In 1965 my parents purchased the house at Turkey Lane in Cold Spring Harbor. Lovers of rescuing old houses, they intended to restore it to a functional abode for our family of six. They had been told it once had belonged to a whaling captain, which is most likely a stretch, as the house is not of the size nor quality typically associated with a sea captain. Be that as it may, we set out to make the dilapidated house habitable again. First on the list was to make sure there were no varmints hiding anywhere. To this effort I, being the smallest and most gullible 9-year-old, was sent into the crawl space under the kitchen to see if there was anything under there. While crawling around on my belly with a dim flashlight my beam hit a white object amid the dirt and rubble. I pocketed the object and retreated as quickly as I could wiggle out of the creepy space, thoroughly spooked even though I hadn’t encountered a single varmint. Once I felt secure in the knowledge that my parents would let me keep the object (it did have a naked lady on it after all!), my mom told me it was the bowl end of an old clay pipe. It has stayed with me, neatly boxed, tucked away, and forgotten for nearly 60 years. I recently came across this quirky little piece of Cold Spring Harbor’s history gone astray at the bottom of a long-ignored box and felt it should go back to whence it came." What Nan found under her kitchen floor was the stummel part of a pipe, the largest part of a pipe where the tobacco was lit. With the help of Robert Hughes, the Huntington Town Historian, museum staff are able to share details about the house under which this remarkable find was recovered. According to a Building-Structure Inventory form from 1979, this house was once the Henry Roger’s Farm House, built somewhere around or before 1839. It has been the home for families like Nan’s for quite some time. From what we can tell, the main structure of the house is a wonderful time capsule in itself. It is “a fine example of its period and almost entirely unaltered” according to the report, with shingles and hewn beams. “The house as it now stands is important for its multiple association with the Roger’s family, the earliest and largest owners in the valley through which Turkey Lane runs.” Though this was likely a farmhouse originally, given the maritime nature of our community, I would not be surprised if there was a sailor living here at some point in the past. He probably spent some time wondering where his beautiful pipe went! Nan is not the only local to have brought our museum clay pipes as donations to our collection. The following two examples were donated to the museum by Guy Cozza in 1997; they had been found on the nearby property of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. For more information on historic clay pipes, start with these two posts:

“Clay Trade Pipes” published by the Peach State Archaeological Society: https://peachstatearchaeologicalsociety.org/index.php/12-pipes/157-kaolin-clay-trade-pipes “White Ball Clay Pipes” published by the University of Virginia: https://explore.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/show/layersofthepast/multiplenarratives/imported_pipes

0 Comments

As we prepare for our event on Sunday, February 4 from 11-4pm, we welcome you to our enchanting annual event -- in rhyme. The event title "Narwhal Ball" was first conceived by Anthony Sarchiapone, the museum's Board President. The idea grew from an original event idea for an adult crowd, and shaped over time into a wintry celebration for children, complete with crafts, ice cream and an appearance by Elsa -- and, hopefully, learning a thing or two about arctic whale species! We took inspiration from a previous frosty event the museum held at the height of the "Frozen" film craze. In 2023, our museum team was delighted to welcome 400 visitors at our new event and see such positive interest from the community. This week, we have been spending our time suspending snowflakes with fishing line around the exhibits, moving tables, plugging in tinkly lights, hanging up streamers in the workshop, and getting ready for you to visit. In the meantime, Anthony thought he would share a poem he wrote that imagines a magical place where narwhals really do celebrate! Let’s all go to the narwhal ball, Where narwhals dance In the narwhal hall. Where snowy friends come together And no one minds the frosty weather.

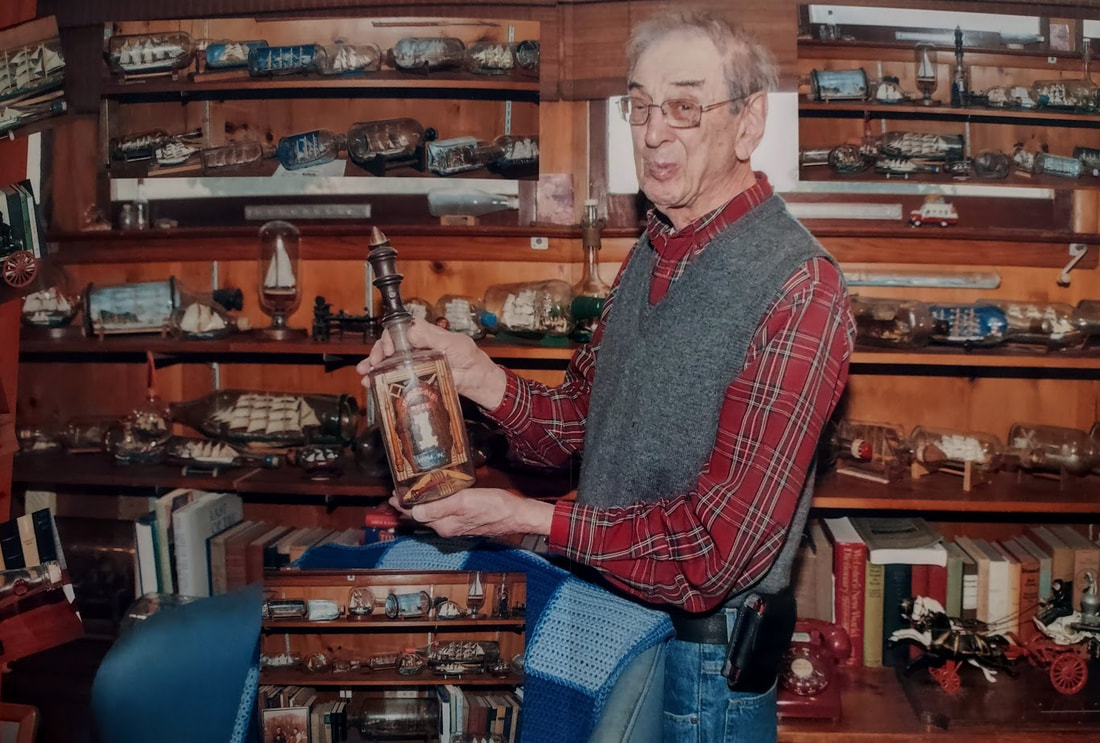

By Anthony Sarchiapone The Whaling Museum Receives Significant Collection of 19 Ships in a Bottle From Kappel Family8/22/2023 When Jeff Kappel’s father passed away this May just a few months shy of his 100th birthday, he was faced with the decision of rehoming his father’s extensive collection of Ships in a Bottle. Jeff chose 19 items to donate to The Whaling Museum’s collection, saying “I want it seen. My father collected for years and loved sharing his collection with people, and I want to continue that.” The craft of ship in a bottle is a finely crafted and challenging folk art. The earliest surviving models date to the late 1700’s. Popularized by both American and European mariners who needed to pass long hours at sea, the creator would use a discarded bottle, bits of wood and other materials to create a tiny yet accurate model of a sailing ship. With great patience for handiwork, the model was created with complete but collapsible rigging, which was inserted folded into the neck of a bottle, set into a painted diorama, and had the sails raised. Each ship in a bottle is unique, and was often created as a gift or souvenir. Retired seamen also maintained their skills by engaging in the hobby. Lester Kappel spent a lifetime collecting ships in a bottle, some of which were loaned years ago to the Whaling Museum for a special exhibition about the craft.

A selection of ships in a bottle from this collection will be exhibited in the Museum’s craft workshop by September 2023 and will be on display thereafter. Summer hours at the museum are Tue-Sun, 11-4pm. Beginning September 3rd, fall hours start and the Museum gallery hours change to Thu-Sun, 11-4pm.

by Claire Spina |

| New York artist Hulbert Waldroup captures Concer’s heroism in a two-sided portrait painted on salvaged ship wood. One side shows Concer at work, bravely aiming his harpoon at a whale. On the opposite, he stands along a shore, grinning as he extends a hand towards us. Waldroup’s piece allows viewers to interact with Concer in two different environments, one that demonstrates his remarkable courage and professional success, and one that emphasizes the valuable spirit of Concer as an individual, beyond his achievements at sea. In employing this duality, Waldroup communicates the importance of Concer’s contributions, without reducing him to a token or statistic. “I give the viewer the opportunity to find and reshape the spaces where they find themselves,” says Waldroup in his artist statement. His rendition of the story acknowledges the unlikely circumstances of Concer’s success while maintaining a sense of optimism and endurance that bears relevance today. This balance is a persistent aspect of “Whalers of the African Diaspora.” Despite the heavy subject matter, an inspiring narrative runs through the exhibition, highlighting the unique contributions of every whaler, innovator, and artist involved. The show extends beyond those at sea, honoring the impact of African Americans on spirituality, culture, labor laws and innovation. Each artifact on display – from ship parts to scrimshaw carvings– are powerful symbols of Black whalers’ presence in the industry, both on and offboard. As Grier-Key puts it, “My hope is that the viewer comes away with new knowledge that is a deeper understanding of not just remarkable achievements but the ordinary spirit of service and justice that is within all of us to bring about change.” Given the show’s inspiring subjects and stories, Grier-Key’s statement rings true. By celebrating those who changed the course of the whaling industry, “Whalers of the African Diaspora” offers everyone the opportunity to learn, grow, and make a difference. |

While developing content for our new special exhibit, "From Sea To Shining Sea: Whalers of the African Diaspora," museum staff came across a recipe for for an oversized ginger cookie dating back to colonial times -- the Joe Frogger Cookie.

The cookie's creation is attributed to Lucretia Young, who was born in 1772 to two formerly enslaved people in Marblehead, Massachusetts, a seaport. She married Joseph Brown, the son of an African American mother and Wampanoag Nation father, and who had been born into slavery to Rhode Island sheriff slaveowner Beriah Brown II. Little is known of Joe's early years, but he enlisted as a soldier in the Revolutionary war to take the place of his enslaver's son, who Joe said "left the company to go privateering." Beriah promised his liberty if he would serve out his son's time. Joe completed his enlistment in 10 months and 20 days, serving with 60 other men, and left the war a free man.

During a time when unemployed freed Black people had to leave Marblehead, Lucretia and Joe operated a successful and busy tavern serving sailors. The building still stands today.

There, Lucretia mixed sea water, rum, molasses, and spices to create a large, gingerbread-like cookie which sailors bought by the barrel - The Joe Frogger. While the exact origin of the name is unclear, as legend has it, she named the cookie after her husband and the nearby pond's wide, flat lily pads. Because the cookies lacked milk or eggs, the rum-preserved cookies had a long shelf life suitable for sea voyages, and were popular with fishermen and sailors.

Joe and Lucretia were free people and property owners in a time when most African Americans were enslaved, yet its star ingredients— rum and molasses—are inextricably tied to the brutality of slavery.

| Recipe: Joe Frogger Cookies 3½ c flour | 1½ tsp sea salt 1½ tsp ground ginger | ½ tsp ground cloves ½ tsp grated nutmeg ¼ tsp allspice | 1 tsp baking soda 1 c molasses | 1 packed cup brown sugar 2 tbsp white sugar ½ c room temp butter, margarine, or shortening 2 tbsp dark rum 1/3 c hot water Mix dry ingredients; set aside. Beat together the molasses, brown sugar, and your chosen fat until fluffy. In separate bowl, combine hot water and rum. Stirring continuously, alternate adding the dry ingredients and the water-and-rum mixture to the sugar-and-molasses mixture. Continue stirring as the mixture coheres into a dough. Cover and refrigerate for at least two hours and up to a day. Preheat oven to 375. Roll out the dough on parchment paper sprinkled with sugar until it’s about ¼ of an inch. Use an empty coffee can or a wide jar to cut out circles in the dough (traditional Joe Froggers are large, like lily pads). Bake on greased or parchment paper–lined baking trays for 10 to 12 minutes until beginning to brown on the edges, and are still slightly soft in the center. Share your pics @ cshwhalingmuseum! |

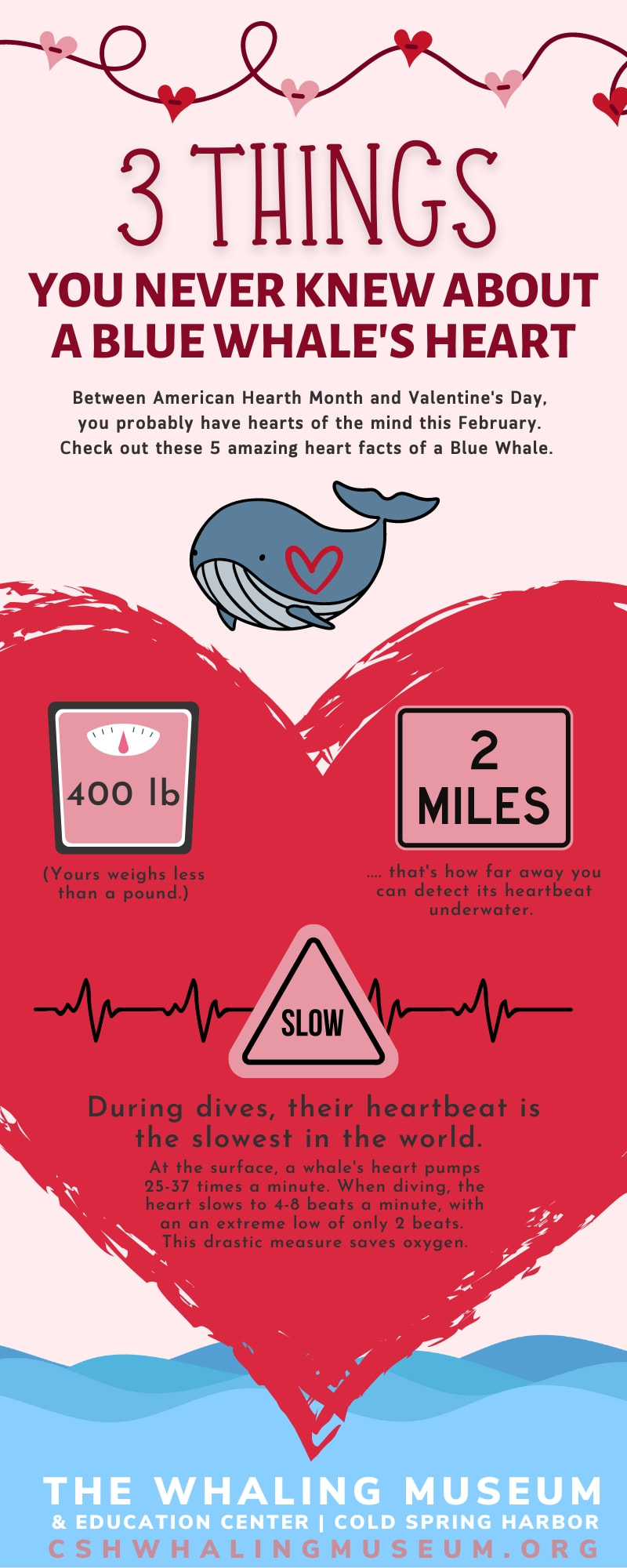

This year, we are resharing several amazing facts about these leviathans' hardest-working organ.

Between American Hearth Month and Valentine's Day, you probably have hearts of the mind this February. Check out these 5 amazing heart facts of a Blue Whale.

- 400 lb in weight! Yours weighs less than a pound!

- 2 miles .... that's how far away you can detect its heartbeat underwater.

- During dives, their heartbeat is the slowest in the world. At the surface, a whale's heart pumps 25-37 times a minute. When diving, the heart slows to 4-8 beats a minute, with an an extreme low of only 2 beats. This drastic measure saves oxygen.

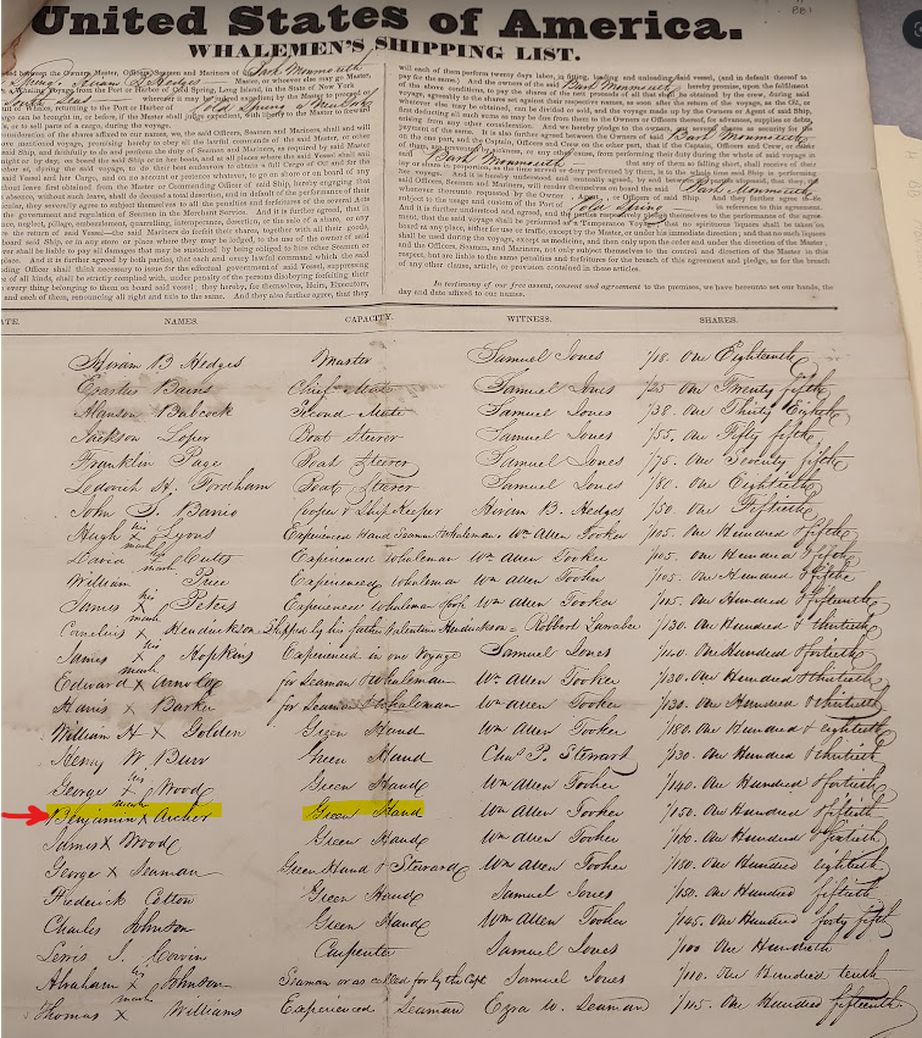

Bob's great-great grandfather, Benjamin Archer (1825-1868), sailed as a greenhand, or an inexperienced crew member on Cold Spring Harbor's whaleship, the Monmouth.

According to FindAGrave, Benjamin was an immigrant from England, and he married Phebe Wall (1827-1898) from Ireland. At the young age of 17, he signed on as a greenhand on the bark Monmouth, as shown in the Museum's archives.

Benjamin sailed on the Monmouth from 1842-1843, which journeyed to the Indian, North Atlantic, and South Atlantic oceans. The captain of the voyage was the well-liked Hiram B. Hedges of East Hampton (1820-ca.1861), who himself started as a greenhand and worked his way up to captain. Although just a few years older than Benjamin, Hiram was known as "always kind to his men, and highly respected by them." He was also "the handsomest captain who made port in the Sandwich Islands in his time.” Benjamin would have had to follow Hiram's no-liquor regulation on the voyage.

Like all greenhands, Benjamin's earnings were small - a cut of 1/150. As a whole, the voyage was comparatively short and profitable, yielding 75 barrels of sperm oil, 1,550 barrels of whale oil, and 12,400 pounds of baleen & whalebone. One voyage seems to have been enough for Benjamin, because we do not see record of him returning on a future voyage. However, he kept his connection to working on the waters, sailing as a local captain of several schooners and sloops in the 1850's-60s in Cold Spring Harbor (you can check out his licenses in our digital collection).

Interestingly, Capt. Hiram B. Hedges - like Benjamin - also retired from whaling. Although Benjamin and many of his descendants remained local to our area, 37-year old Hiram called it quits and moved to Oregon with his wife and son where he became a farmer before vanishing around 1861, possibly in a boating accident - or by committing suicide while facing onsetting Huntington's disease, which ran in the Hedges family. He left behind three young children. (See "The Woman Who Walked Into the Sea.")

Bob Archer noticed some of the museum's recent Facebook posts, and he came to see the collection for himself in person. As an added connection to the museum, Robert's wife, Kathleen, was a descendant of Captain James Wright, whose home is used today for our museum offices and collection storage.

Interestingly, Bob shared that years ago, Cold Spring Harbor was not loally regarded as the "well-off" location it is thought as today - Cold Spring Harbor residents were nicknamed humble "clammies"!

| Fundraising isn't always our favorite part of the job - but this year, John's Crazy Socks made our annual appeal much more fun than usual. The Whaling Museum family is tremendously grateful to our good friends at John’s Crazy Socks, who provided special Whale Socks that the museum used as thank you gifts for donations. Donors who made a donation of $50 and up received a fun pair of whale socks in return. It was a big hit and stirred extra generosity new museum supporters. These beautiful Whale Socks are available in both women’s and men’s sizes (psst - John’s Crazy Socks even donates 10 percent of the sales all year long to the Whaling Museum, too!). John Cronin, co-founder and Chief Happiness Officer at John’s Crazy Socks, said, “I love the Whaling Museum and want to do everything I can to help them. I have been going to the museum for years and I love their special events like scavenger hunts.” Nomi Dayan, the Executive Director of the museum said, “We are so grateful for the support of John’s Crazy Socks not only for the donations they have made to museum over the past five years, but also for the spotlight that John’s Crazy Socks puts on our museum activities throughout the year.” |

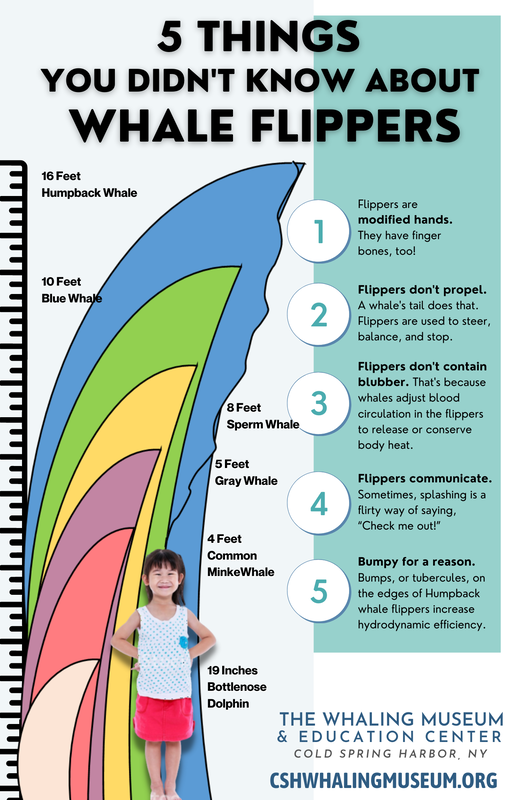

- Flippers are modified hands. They have finger bones, too!

- Flippers don't propel. A whale's tail does that. Flippers are used to steer, balance, and stop.

- Flippers don't contain blubber. That's because whales adjust blood circulation in the flippers to release or conserve body heat.

- Flippers communicate. Sometimes, splashing is a flirty way of saying, “Check me out!”

- Bumpy for a reason. Bumps, or tubercules, on the edges of Humpback whale flippers increase hydrodynamic efficiency.

19 Inches: Bottlenose Dolphin

4 Feet: Common Minke Whale

5 Feet: Gray Whale

8 Feet: Sperm Whale

10 Feet: Blue Whale

16 Feet: Humpback Whale

Special Guest Contributor

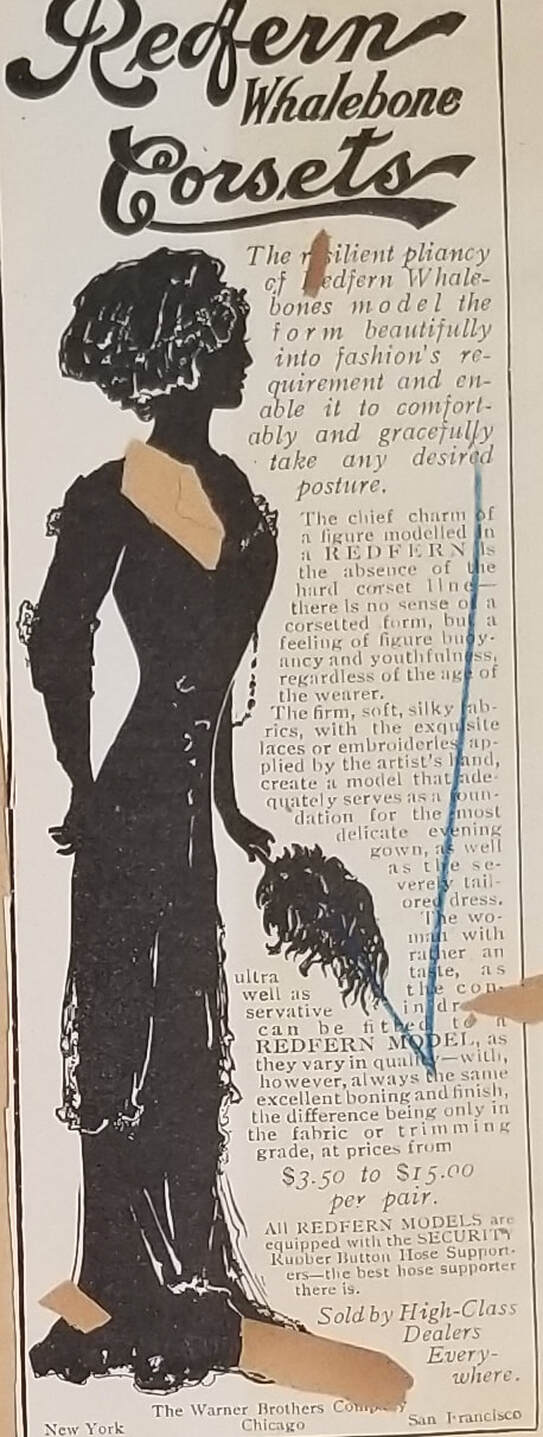

This source raises a very interesting question; what is this woman thanking the whale for? For what did a woman owe a whale? These four advertisements, selected from the Bridgeport History Center archive, offer some possible answers. Some of the main selling points are comfort, quality, and luxury, though there are certainly others. Do you find these points persuasive? Would your mother, grandmother, or great grandmother?

The Warner Brothers Company produced and promoted whalebone corsets from 1894 until 1912. Redfern advertisements from 1894 to 1912 are rich in detail, explaining why a contemporary woman should purchase a whalebone corset for $15.00 to $3.50 over other, cheaper models boned with plant fibers, steel, feather shafts, or celluloid. At the turn of the twentieth century the necessity, purpose, and impact of corsetry was just as hotly contested then as it is today, though other garments have since replaced them. Advertisements such as the following examples contributed to the longevity of the American whaling industry by sustaining a demand for bowhead baleen in luxurious corsets at a time when the industry’s security in traditional markets, fuel and illumination for example, was threatened by cheaper and more readily available alternatives. Between the 1880s and 1910s, whalebone represented the most stable and secure market for the American whaling industry despite the rising price and unreliable quality of the material. The advertisements will help to explain why women continued to wear whalebone.

All Redfern Corsets were boned with whalebone, but only those of the highest quality used imported silks, coutil, ribbons, laces, and other finery, artfully applied by Redfern designers. This attention to detail in design and material was the same paid to couture design, and gave the Redfern the status of a couture corset. “The firm, soft, silky fabrics, with the exquisite laces or embroideries applied by the artist’s hand, create a model that adequately serves as a foundation for the most delicate evening gown, as well as the severely tailored dress.” Advertisements for Warner’s Redfern Whalebone Corset promised quality, luxury materials and a comfortable, fashionable form. In essence, they promised the quality of a custom made Parisian corset at half the price.

Before Warner’s could market a luxurious couture quality corset, they had to first be able to produce one affordably. As The Fashionable Woman said quite succinctly: “You may pay from Fifteen Dollars to Thirty-five dollars for a corset that is custom made - the trimming may please your eye - but the actual shaping and wearing do not compare with the Redfern Whalebone Corsets which cost from $15.00 down to $3.50 per pair.” This was accomplished through the industrialization of corset manufacture.

In 1912 Warner’s stopped using whalebone. Speculation based on a knowledge of the trends of demand and supply between the whaling and corset industries leads to the conclusion that prices had gotten too high, imports too scarce, and the quality of the bone too unreliable. One of the key features of a Redfern was the quality of its whalebone. The Warner Company went to great lengths to secure their whalebone, but once the quality could no longer be reliably secured the company turned to alternative boning, likely their patented Rust-Proof Steel.

Advertising played a crucial role in securing a market for whalebone by sustaining demand and generating desire for the material, for fashionable couture quality whalebone corsets, into the twentieth century. In the case of the Redfern Whalebone Corset, desire for the whalebone product was produced by an appeal to period conceptions of quality, luxury, and aesthetics. A Redfern woman was beautiful because her form conformed to Parisian models without too much undue constraint. A woman in a Redfern had the whale to thank for her beautiful, fashionable figure.

Why

Follow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests.

Categories

All

Black History

Christmas

Fashion

Food History

Halloween

Individual Stories

July 4

Medical Care

SailorSpeak

Thanksgiving

Whale Biology

Whales Today

Whaling History

Whaling Wives

Archives

May 2024

January 2024

August 2023

March 2023

February 2023

September 2022

February 2022

October 2021

July 2021

June 2021

February 2021

November 2020

May 2020

April 2020

February 2020

December 2019

September 2019

August 2019

June 2019

May 2019

February 2019

December 2018

October 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

October 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

March 2017

October 2015

Author

Written by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed