|

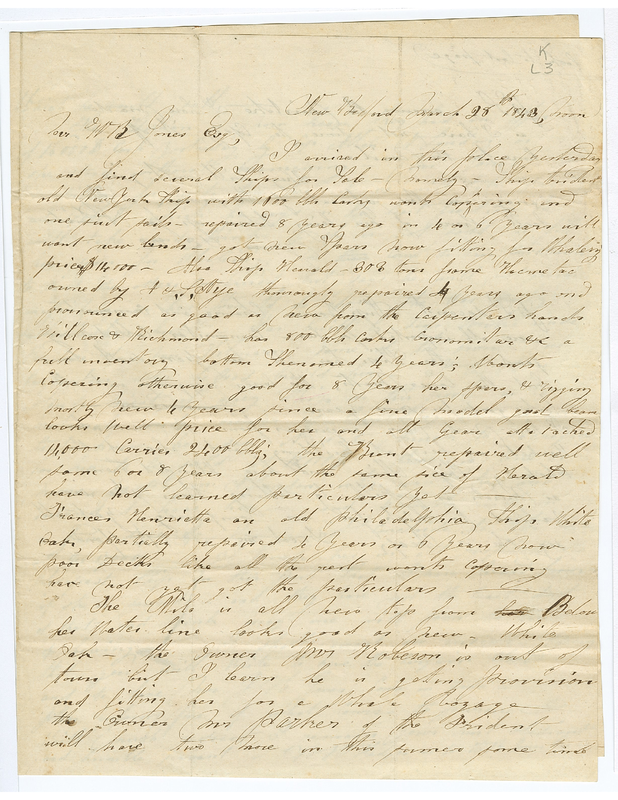

By Elizabeth Marriott, Collections & Exhibits Coordinator The Whaling Museum's archives offer insight into the process of purchasing a vessel for use as a whaleship. In 1843, Cold Spring Harbor was in need of an additional whaling ship. Its ships were all at sea, and the Cold Spring Whaling Company was looking to expand. At this time, few ships were built for whaling; instead whaling companies bought trading vessels such as packet ships and retrofitted them for whaling. (Of Cold Spring Harbor's 9 vessels, only 1 - the NP Tallmadge - was originally built for whaling.) The best converted whaleships maximized speed and carrying capacity. Packet ships were designed to hold large, heavy cargo and could be easily adapted to hold oil casks. Typically the biggest modification needed to convert a trading vessel to a whale ship was adding the tryworks - a brick furnace with giant cast-iron kettles used to render blubber into whale oil. The Cold Spring Whaling Company rehired Captain William H. Hedges, a captain from East Hampton who successfully led several whaling voyages for Cold Spring Harbor. He met some feisty whale in his lifetime: a whale he harpooned struck the head of his whaleboat and tossed him into the water, where his boat crew hauled him to safety. Hedges traveled to New Bedford to inquire about vessels for sale. At the time, New Bedford was one of the busiest ports in the country and it wasn’t unusual to find 4 or 5 vessels for sale at any one time. This 1843 letter to Walter R Jones (part-owner of the Cold Spring Whaling Company) from Captain Hedges gives us insight into the process, where he describes ships for sale including cargo space, speed, and major repairs in the ship’s history. Excerpts: New Bedford March 28th 1843, Noon Dear WR Jones Esq, I arrived in this place yesterday and find several ships for Sale – namely – Ship Trident, old New York Ships with 1000 barrels carries want coopering and ... sails- repaired 8 years ago in 4 or 6 years will want new bench... fitting for whaling prices $14,000. The Ship Herald – 303 tons frame owned by A,O, S, Nye thoroughly repaired 4 years ago and pronounced as good as new from the carpenters hands ... otherwise good for 8 years, her moors & rigging mostly new ... looks well priced..." Based on Hedges' description, compare these three ships for sale:

Hedges was most excited about the possibilty of buying the Roman. He continues: "The ship has all her spars ... the lines, rigging, and all looks good for some years - I have made my inquires from the men who worked on her at building, and who at the Whaling Ship Office and have blinded them as much as possible by telling them she was valued to[o] high for our Company yet all say she is cheap- [illegible] at N. Bedford They had an offer of $ 16000 cash yesterday by Cap Allen, N London... Mr. Jones is willing for us to have her if we will take her at 17000 $ which he says is the least fraction he will take and thinks if she is not sold to fit her soon for whaling, he then came to this conclusion to suit the others concerned, but says he will not sacrifice any more on her than to do so ... there is one or more people in N London who want her and intend to have her- and probably will in a few days if we do not conclude to take her at the $17,000. I think her in all respects the cheapest ship in this part that I have heard from if she is sound- and they have not the least doubt of that... I shall await an answer- hoping that you will write to have the bargain closed and to have Mr. J H Jones come on soon- please inform me of what course to pursue.... Your most obedient and humble servant- W.H. Hedges" The expense must have been too high in the end, because Captain Hedges left New Bedford without purchasing any ship. Based on the expense account he submitted to the Cold Spring Whaling Company, Hedges arrived in New Bedford on March 27th and returned to Cold Spring in June. Hedges did recruit a boatsteerer - so the trip was not a complete loss! Ultimately, the company went on to purchase the Nathaniel P. Tallmadge, likely at a good price from the floundering Dutchess Whaling Company in Poughkeepsie, who was trying to stave off bankruptcy. Fully outfitted, this whaler was ready to go. Hedges commanded the Tallmadge on his last voyage from 1843-1845. Hedges and his crew still faced feisty whales when a whale smashed a whaleboat gunwale. The boat was towed back to the ship with rapid bailing and clothes stuffed into the hole. Hedges retired from the sea and opened a store with his brother-in-law in Plattsburgh. All together, the Tallmadge made four successful voyages from 1843-1855, bringing in a total of 8,410 barrels of whale oil, 245 barrels of sperm whale oil, and 53,390 pounds of bone before being sold in New York City. The ship carried freight to and from New Orleans; a year later, she was rebuilt as a bark, renamed Norwood, and sold abroad. Explore More:

Find out more about Cold Spring Harbor's whaling history in Mark Well the Whale by Frederick P. Schmitt - Available in the Museum gift shop

0 Comments

Text transcribed for screen readers for those who are visually impaired:

WHY DID WHALERS CELEBRATE THANKSGIVING MORE THAN ANY OTHER HOLIDAY? Much of the Thanksgiving "story" is myth. Yet many of the current Thanksgiving traditions were formed in the 1800's. It Made Most Americans Feel Patriotic

She Told Me to!

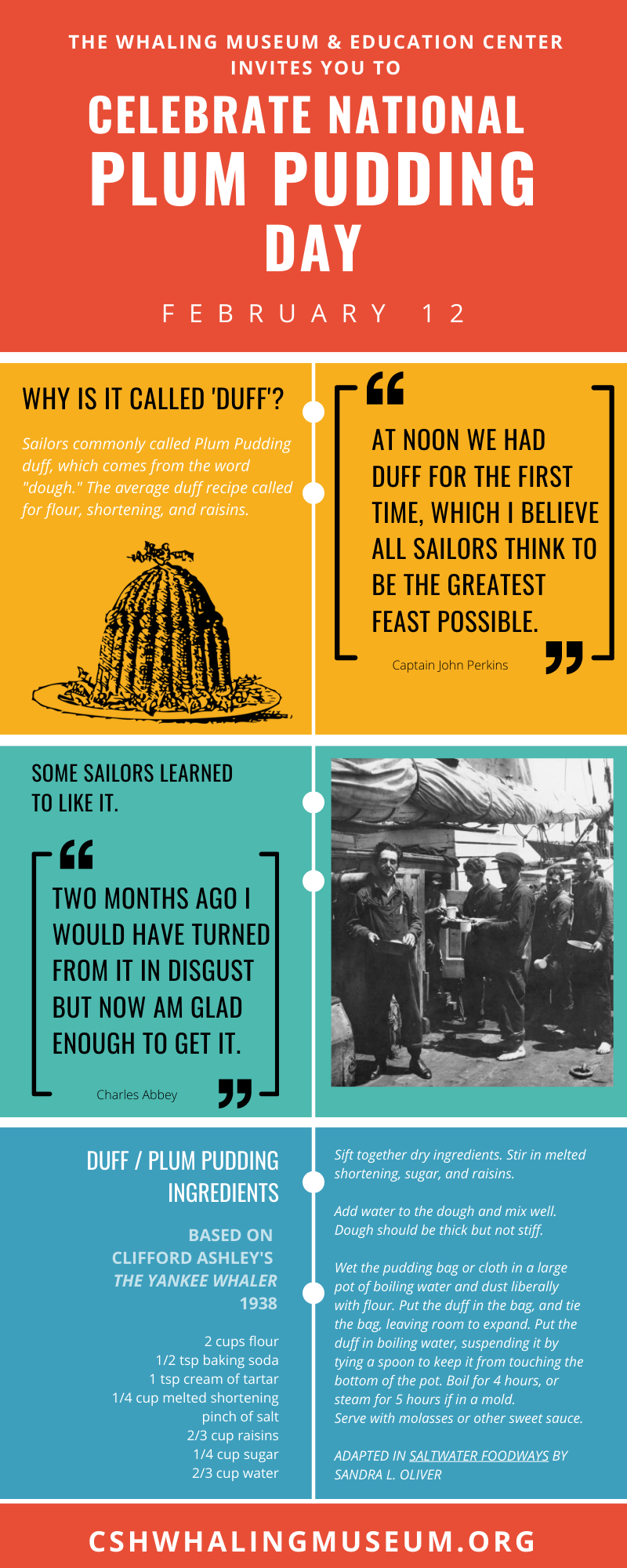

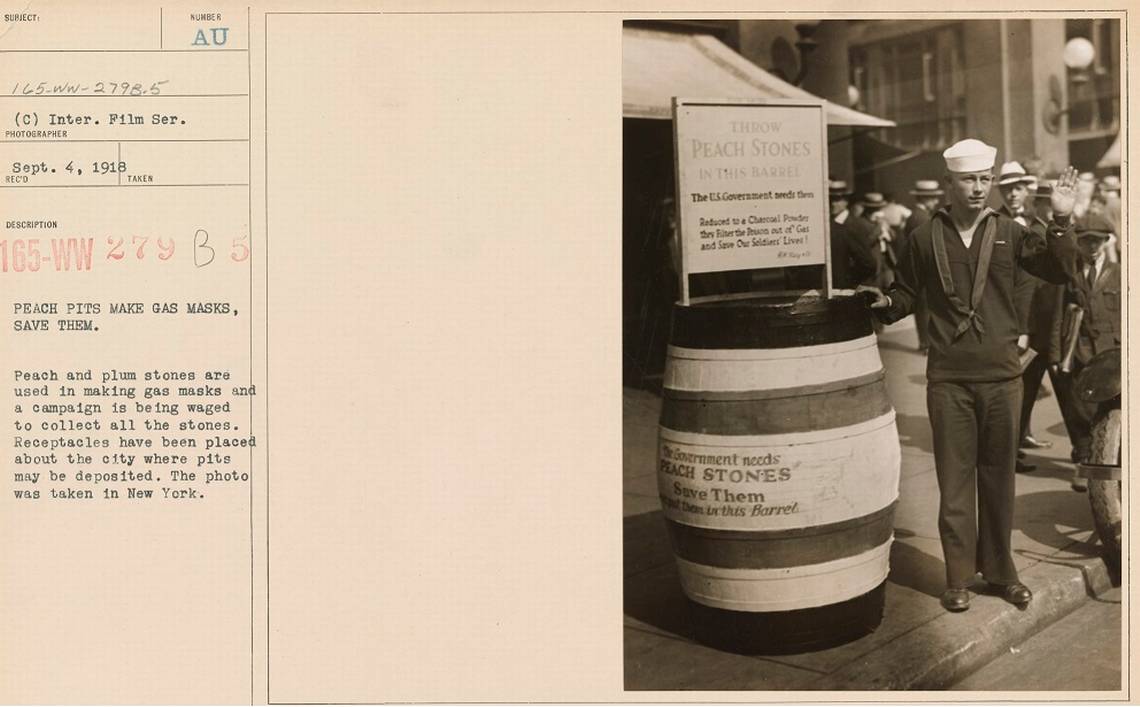

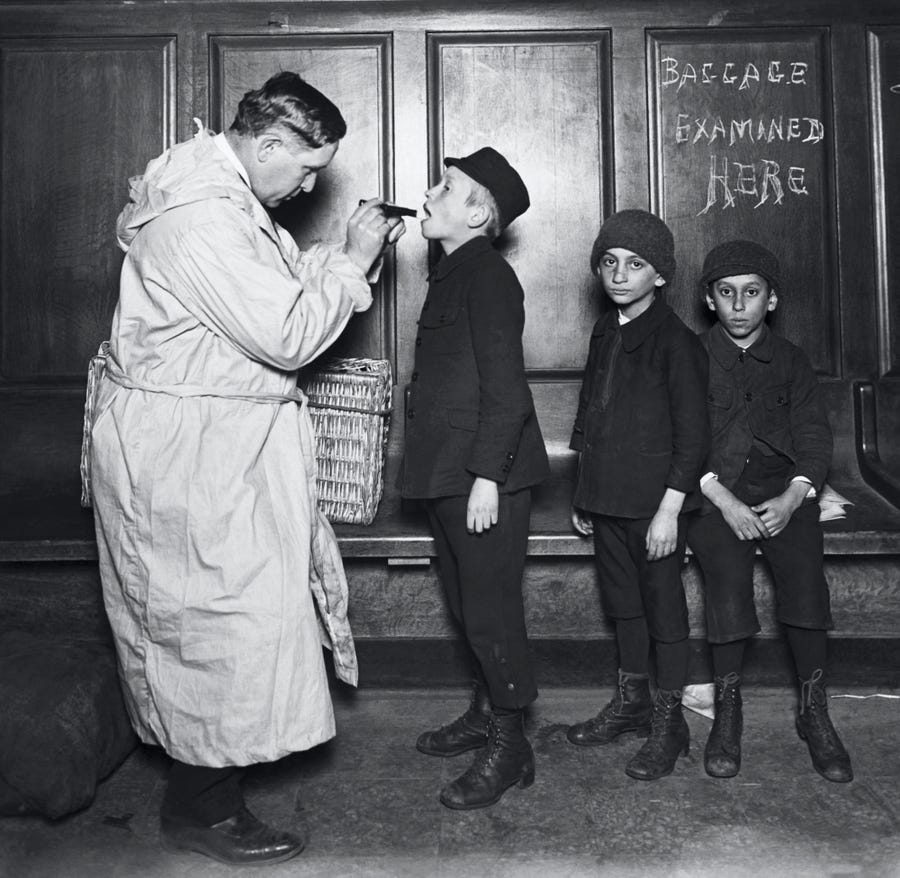

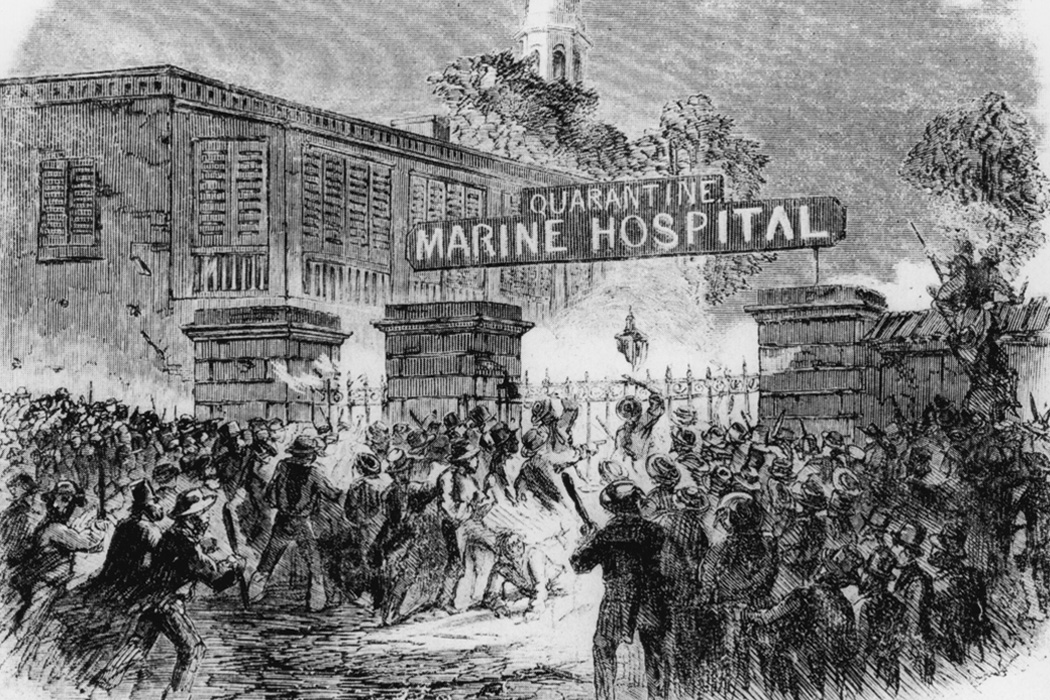

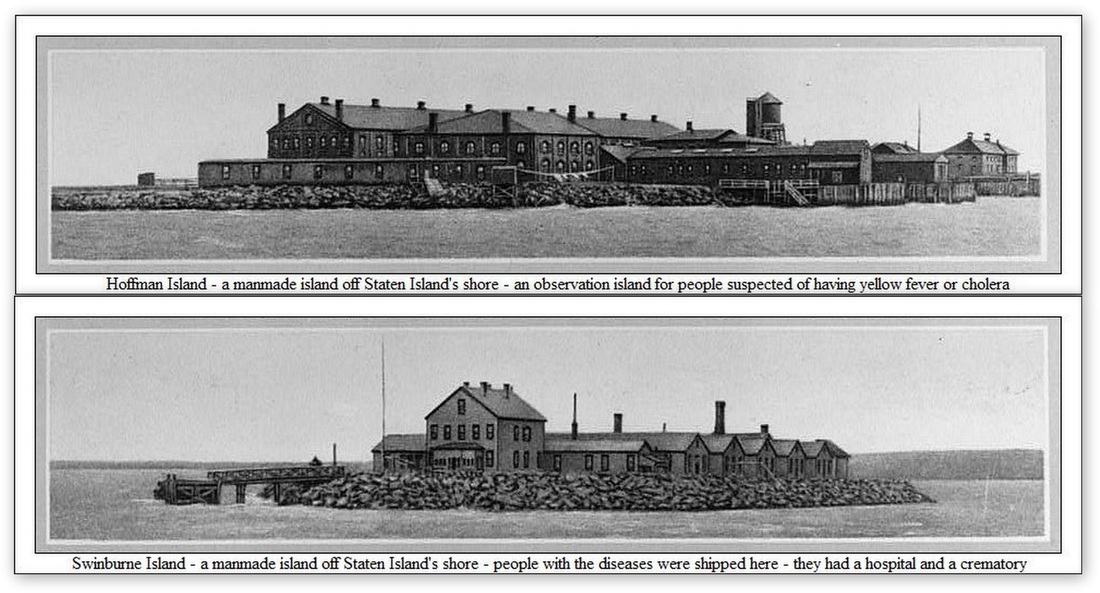

Happy Thanksgiving Day! by Joan Lowenthal A 1918 call for supplies mirrors the health crisis today. The Red Cross made an urgent plea for masks for the doctors and nurses in quantities and at once. The Cold Spring Harbor branch spread the word that, “A special order for contagious ward masks has been received and the masks are being made at the Red Cross room and every evening in the Library. Members and their friends are urged to help with this work until the order is completed.” (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, October 04, 1918, Page 7) In 1918, not only was there a worldwide flu pandemic, but World War I was still being fought. Gas masks for men at the front line were desperately needed and the local Huntington Red Cross encouraged people to collect peach pits, nuts and other fruit pits also called stones and drop them into the receptacles found in several local stores. The government needed 750 tons of peach stones, plum stones, olive pits, and all hard nut shells especially coconut shells to supply charcoal for gas masks each day. The charcoal derived from these stones was forty times as strong as ordinary charcoal. Two hundred peach stones were needed for one gas mask. This was a nationwide nut-gathering campaign. (The Long Islander, Huntington, NY, September 13, 1918, Page 1) By the beginning of October 1918 Huntington had done very well in saving their peach stones and other nut shells. Barrels and barrels were collected and shipped to a carbon plant where machinery ground up the bits and the material was distilled to uniform-sized carbon pieces. The powder was then shipped to the Gas Defense Plant New York located in Long Island City, NY where factory workers assembled gas masks. (Laura Corley. “How peach pits helped American allies win World War I,” The Macon Daily Telegraph, November 12, 2018.) People in the Huntington area responded so enthusiastically that it was not necessary to ask the Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls to canvas for nuts door to door. But these boys and girls were asked to pick up the peach stones in the local orchards. “There should be no peach stones left in the orchards doing no one any good, when they might save some precious life. (The Long Islander, Huntington NY , October 04, 1918, Page 2) There was an urgent appeal for nurses all over the country to replace the nurses that were sent overseas and to home military camps. The Long-Islander attempted to entice young women to become nurses. “The profession of nursing is one that should appeal to the ambition of young women fitted for the work; the pay is good and it is never overcrowded. In its higher branches it closely approaches the profession of the surgeon in its educational requirements.” The Long-Islander, Huntington, September 13, 1918.  The first wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic was fairly mild and many people recovered and the death rate was low. By the end of the summer of 1918 the second wave of the virus was virulent, highly contagious and deadly. In fact, the highest fatality rate of the pandemic was October 1918. Victims of the disease died within hours or days of developing symptoms and many were young adults. Local Long Island newspapers only mention the flu in the spring of 1918 infrequently, but by the fall especially in the month of October there are numerous accounts of local people dying and closings of churches, schools, and cancelling of events. The Jones family whose descendants started the Whaling Company in Cold Spring Harbor lost a member of their family due to the “Spanish Flu.” Philip Livingston Jones died at the Jones Manor Farm in Oyster Bay, NY. He was only 28 and left a wife and young son.(The Long Islander, November 01, 1918, Page 5). Sadly his mother Mary Elizabeth passed away the week before of a stroke at the age of 64 and his older brother Oliver Livingston Jones passed away the previous March at the age of 38. His death certificate lists bronchial pneumonia as the reason for death which were complications of the Spanish Flu. The devastating second wave of the “Spanish Flu” occurred in the US because returning soldiers infected with the flu spread it to the general population. Especially hard hit were densely populated cities. Many city governments were not ready for the onslaught. Philadelphia went ahead and had a Liberty Loan parade which was attended by tens of thousand of people. The disease spread like wildfire. In 10 days about 1,000 Philadelphians were dead and about 200,000 sick. By contrast citizens in San Francisco were fined $5 if they were caught in public without masks. The “Spanish Flu” took a toll on the economy. Even mail delivery and garbage collection was impeded and in many places there were not enough farm workers to harvest crops. Nonessential businesses were not mandated to shut down, but they were forced to shut down because so many employees were sick. Does history actually repeat itself? For more info check out: By Joan Lowenthal We are in unprecedented times. Many of us never thought a quarantine of practically the entire world could happen in 2020. It seems like science fiction.  14th century ship 14th century ship When did the practice of quarantine as we know it begin? It actually began during the 14th century as an attempt to protect coastal cities from plague epidemics. Ships coming into Venice from infected ports were mandated to sit at anchor for 40 days before anyone could come to shore. The word quarantine was derived from the Italian words quaranta giorni which means 40 days. When the United States was first established there was no federal involvement in quarantine regulations. It was not until 1878 that the United States Congress passed federal quarantine legislation. Up to this point protection against imported infectious diseases fell under local and state jurisdiction. By 1846 all ships coming into New York Harbor had to anchor off near Staten Island for quarantine inspection. The ships were boarded and if any signs of disease were found all the passengers were taken to the Quarantine Hospital on Staten Island which was opened in 1799 and called the Quarantine. First-class passengers were taken to St. Nicholas Hospital at the Quarantine and steerage passengers were taken to smelly, overcrowded bunkhouses stripped naked and disinfected with steaming water. [1] The ship then had to remain in quarantine for at least 30 days and sometimes as long as six months. There were as many as eight thousand patients in the hospital in a year. It was very dangerous work for the staff and funeral expenses for employees was a category in the accounting books. Many people who lived on Staten Island did not like the nearness of the hospital and in 1858 angry well-prepared vigilantes set fire to the buildings. Two people died that night. Check out When New Yorkers Burned Down a Quarantine Hospital by Matthew Wills (September 19, 2019) daily.jstor.org. Quarantine facilities were then moved off-shore to a boat named after Florence Nightingale, then two islands off of Staten Island. The two islands were built with land fill in the Lower Bay - Swinburne Island in 1860 and Hoffman Island in 1873. These small islands were used as quarantine islands until the 1920s. The conditions were horrifying. Today these islands are uninhabited and off limits to the general public although you can go past them in a boat. In the summer of 1892 there was a terrible cholera epidemic and several ships that came from Hamburg, Germany were kept quarantined. Many of the people on board were refugees from Russia fleeing the reign of Czar Alexander III. A cholera epidemic swept through Russia and passengers both in steerage and cabin class died from the disease during their voyage. They were seeking a better life in the United States. What is little known is that the Governor of New York at the time, Governor Flower, authorized the purchase of the Surf Hotel, an aging hotel on Fire Island to be used as a quarantine station for some of the passengers from the infected cholera ships in New York Harbor. There was tremendous opposition and two hundred deputized officers of the Islip Town Board of Health tried to stop the passengers from getting off the ship. The Islip Town Board of Health disputed the right of the State to use the island as a quarantine station. [2] Local baymen feared their livelihood was at stake when oyster houses in New York City began cancelling orders. According to Shoshanna McCollum in an article posted February 23, 2020 “600 healthy cabin class passengers of the Normannia were transferred to a day boat to take the passengers to the Surf Hotel. Unfortunately the baymen turned vigilantes and crossed the bay with clubs and shotguns.” The trip should have taken the day boat several hours, but instead took several days. This must have been awful as the boat was overcrowded and did not have sleeping accommodations nor enough food provisions. Troops were sent by Governor Flower to Fire Island to permit the asymptomatic passengers to disembark. The Surf Hotel served as quarantine headquarters until early October of 1892. Amazingly only two documented cases of illness were reported on Fire Island during this time and those two cases turned out not to be cholera at all. One other interesting note about the Surf Hotel. The owner of the hotel at the time was David Sammis and he sold the hotel to the state for $210,000 which is a value of about $60 million today. This was definitely over-priced. Check out the article by Shoshanna McCollum Plague & Prejudice When Quarantine Came to the Shores of Fire Island. fireisland-news.com There have been pandemics throughout history, but probably the most famous at least up to this point has been the 1918 Flu Pandemic also known as the Spanish Flu. It lasted from January 1918 to December 1920 and as reported by the CDC it was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It infected about 500 million people which was about a third of the world’s population at the time and killed at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,00 occurring in the United States. cdc.gov 1918 Pandemic (H1N1) virus) Many people on Long Island were affected by the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Just one page in The Long-Islander, October 25, 1918, Page 6, Image 6 describes the state of affairs. In Huntington Station “Garrett Van Wicklen, who has been with influenza, was improved, but this week suffered a relapse from which he is recovering.” “The influenza is quite prevalent here this week, and in one family there were four ill with it.” “Owing to the epidemic it has been deemed wise to indefinitely postpone the dance of the Huntington Manor Firemen, which was to have been held in Liederkranz Hall Saturday evening.” “In effort to help the health authorities to stamp out the influenza, no churches were open in this section Sunday. In order that his people should not be deprived of worship, the Rev. Francis X Wunsch had an altar erected on the lawn adjoining St. Hugh’s R.C. Church and celebrated mass out of doors.” “The Greenlawn School is closed by order of the Board of Health during the influenza epidemic. As today, nurses during the Spanish Flu Pandemic galvanized and worked extremely hard putting their own health in peril to save victims of the Spanish Flu. One of these nurses was the daughter of George W. Barrett of Cold Spring Harbor who trained on Cold Spring Harbor whaling ships, The Alice and The Sheffield. The Long-Islander, December 13, 1918, Page 7, Image 7 states that “Miss Laura G. Barrett, who has been visiting her sister has returned to her work at the Henry Street Settlement in lower New York City. When the dreadful Spanish Influenza struck New York City, Miss Wald, who is at the head of the Henry Street Settlement, offered her large staff of 150 nurses to the city. During the time the epidemic raged the amount of work the Settlement was called upon to do was very heavy and taxed them to the utmost. Miss Barrett had much responsibility in her office and was given a short leave of absence for complete rest and has been much benefited by her stay in Cold Spring Harbor.” There was good advice in The Long Islander, October, 4, 1918:

“HEALTH PRECAUTIONS: Don’t get frightened after reading that learned dissertation in our columns this week on Spanish Influenza and take to your bed. It is after all the old-fashioned grip and every time you cough or sneeze it does not signify you are going to have it. Keep your courage up and avoid overcrowded cars and other meeting places. Do not get too tired from overwork and eat moderately. Live in the open air as far as possible.” This is probably good advice for today, too. Text Below for Accessibility

Between Valentine’s Day and American Heart Month, you probably have hearts on the mind this February. Check out these facts of the heart of the world's largest creature, the Blue Whale.

Read More: A Blue Whale Had His Heartbeat Taken for the First Time Ever — And Scientists Are Shocked https://www.livescience.com/first-blue-whale-heartbeat.html National Geographic: Education Blog – How Big is a Blue Whale’s Heart? https://blog.education.nationalgeographic.org/2015/08/31/how-big-is-a-blue-whales-heart/  By Nomi Dayan If you showed a whaler a picture of a contemporary American family celebrating Christmas, he likely would have no idea what holiday he was looking at. Many of the familiar traditions we associate with Christmas today are relatively new. Christmas trees, a rosy-cheeked Santa Claus, and even the seasonal spirit of generosity only took hold in the mid-to-late 1800s. Yet as modern yuletide customs took shape during the Victorian era, Christmas was a different story for whalers at sea. The Captain decided if and how the day was observed. Eldred Fysh was one of the lucky whalers. He wrote aboard English ship Coronet in 1837: “This being Christmas day, there was no work done and the Capt. gave the men the means of making themselves as comfortable as they could do." William Morris Davis aboard the Chelsea (1834-36) of Connecticut was left disheartened. “I wish the world a merry Christmas, but there is no use in wishing a merry Christmas to that unfortunate race, generally known and vulgarly called Blubber Hunters. They have not wherewith to make a merry Christmas. This with us is plain Friday, only that occasionally someone bawls out, ‘I wish you a merry Christmas.’”  Whaleship Splendid Whaleship Splendid A more intimate view of Christmas at sea can be found in the diaries of whaling wives. Many remark celebrating Christmas with a special meal (a delight which may not have extended to the lower-ranked crew members). Eliza Edwards, who sailed from Honolulu on the Splendid of Cold Spring Harbor with her husband Eli, the first mate, wrote: “I don’t believe if you were home on Christmas and I at sea that you had any better dinner than I did. We had roast turkey just as tender and nice as it could be besides vegetables, oyster stew, and mince pie.”  Annie Ricketson Annie Ricketson Annie Ricketson spent several years aboard the whaleship A. R. Tucker. She must have found herself quite bored on Christmas 1871, because all she wrote for that day was, “This is Christmas Morning. Last Christmas, Husband and I were home and we enjoyed ourselves very much.” The next year she found the day just as unremarkable: “Dec 25. The past two days have been very quiet, seen nothing.” The highlight of the day was wishing others Merry Christmas. “This morning before I was up the boy tip toed down the stairs and wished me a Merry Christmas...Mr. Bourne came and looked down the stairs and wished me. But I wished Mr. Harris and Mr. Vanderhoop. But the cook got a head of me. He looked down the sky light just as I sat down to breakfast and wished me. They all seemed very anxious to wish me first.” Nostalgically, she ends her entry, “I suppose they are having nice times at home now, wish I was there to enjoy it with them.” Christmas the following year was not much more exciting for Annie. “Nothing…worth writing about. But cannot pass Christmas by and not have something to write about. This morning I gave Daniel a present of a Cigar holder that I got him in St. Helena. He was very much pleased with it for he had been wanting one for a long time.” It was then back to work as usual: “Raised whales his forenoon – saw them jump out of water once, but it was so rugged saw nothing more of them. We thought we were going to have a nice Christmas present.”  Ambrotype of Minnie Lawrence, Sandwich Islands, date unknown Ambrotype of Minnie Lawrence, Sandwich Islands, date unknown The captain’s children, if present, expected full stockings, even if at sea. When Clara Ryder on the N. D. Chase told her young son there was no chimney for Santa Claus aboard a ship, he thought “he should come down the stove pipe into the galley.” Mary Chipman Lawrence, who sailed with her young daughter Minnie on the whaler Addison, described four Christmases during her life at sea, each where she was careful to fill her daughter’s stocking:

Some whaling wives enjoyed making Christmas surprises for crew members. Mary Stickney on the whaler Cicero in 1881 journaled how she sent the Steward to get the cabin boy’s stockings and secretly fill them with “candy, peanuts, coconuts, and a calico shirt” she had sewed. One Christmas celebration at sea was planned a year in advance among three whaling families who agreed to meet at the tiny Norfolk Island east of Australia on December 25, 1856. And met they did, dining together on board one of the ships. Seventy five years later, three of those children shared the memory again in Nantucket – this time on dry land. Nomi Dayan is the Executive Director of The Whaling Museum & Education Center of Cold Spring Harbor. Upcoming December 2019 Events:

Details: cshwhalingmuseum.org/events We recently asked our honoree, Senator Jim Gaughran, about his life on Long Island and his views on the environment. Tickets for this annual fundraiser, Ports of Call can be purchased here.

Senator, what are some of your first memories of Long Island Sound? How old were you? Some of my first memories of the Long Island Sound involve my childhood spent enjoying the beautiful beaches in Centerport and Northport. I created many great memories of swimming, picnics on the beach, and warm summer days spent with family. These experiences influenced my love, appreciation, and deep admiration for the natural beauties of our world. When and why did you first become interested in environmental causes? As a kid growing up on Long Island my parents bought one of the first major new subdivisions being built. Growing up there were ponds, fields, ice skating, you name it. We spent a lot of time enjoying the outdoors and nature. Slowly one development after another came up, and the ponds and fields and farmland we had enjoyed growing up slowly disappeared and were replaced by houses. This made me acutely aware of the challenges facing our region and the need to champion environmental causes. What would you encourage Long Islanders to do / think about to improve local water quality? I would encourage Long Islanders to continue supporting upgrades to sewage treatment systems that our outdated and lack the safest, modern technology. I would also encourage Long islanders to connect cesspools to existing treatment plants, and where they cannot connect to treatment plants, to connect to other individual treatment systems. I'm a strong supporter of natural methods such as rain gardens and oyster gardening which help improve local water quality. We need to advocate for funding from the federal government to comprehensively address the challenges facing water quality on Long Island. Is there one piece of environmental legislation of which you are most proud? My legislation to close loopholes in the statute of limitations, which will hopefully be signed by Governor Cuomo, will be a tremendous help to public water authorities. This bill will ensure corporate polluters cannot evade their financial responsibility to clean up the pollution they've caused. This will ensure polluters, not ratepayers, pay for the cost of removing contaminants like 1,4-dioxane from our water. By Joan Lowenthal

This post follows up on a previous blog post, What Happened to Scudder Abbott? In the fall of 2018, a visitor to the Museum read an excerpt from the Logbook of the whaleship the Sheffield. He read that on Thursday, May 21st, 1846 while taking in sail at sunset, Scudder Abbott, a crew member on the Sheffield, lost hold and fell about 70 feet from the topsail yard to the deck. He became delirious and blood ran from his mouth and nose. He was immediately taken to the cabin and medically bled and made as comfortable as possible. The next day he was at times sensible and then again quite deranged. The visitor wanted to know if Scudder survived the fall. Did he? Over the next several months Scudder Abbott is mentioned in the ship’s log. Some days he was able to sip some soup and drink some tea and even managed to go up on deck. The last entry about Abbott that our Museum had was on Friday, October 8th, 1846. It simply stated that Abbott was rather better. Our next logbook for the Sheffield begins with November 1847 and there was no mention of Abbott. Recently someone commented on the blog that in fact Abbott had a tragic ending. Our Museum is not in procession of the logbook of this entire voyage of the Sheffield. But the New Bedford Whaling Museum has a transcription of the Sheffield’s entire 1845-1849 voyage. Sadly, it states that on October 11, 1847 “At 10 minutes past 11 am, poor Scudder breathed his last - when he has left up a fond father and mother to morn his melancholy and being their only child - his memories will be committed to the dead tomorrow morning.” By Nomi Dayan, Executive Director

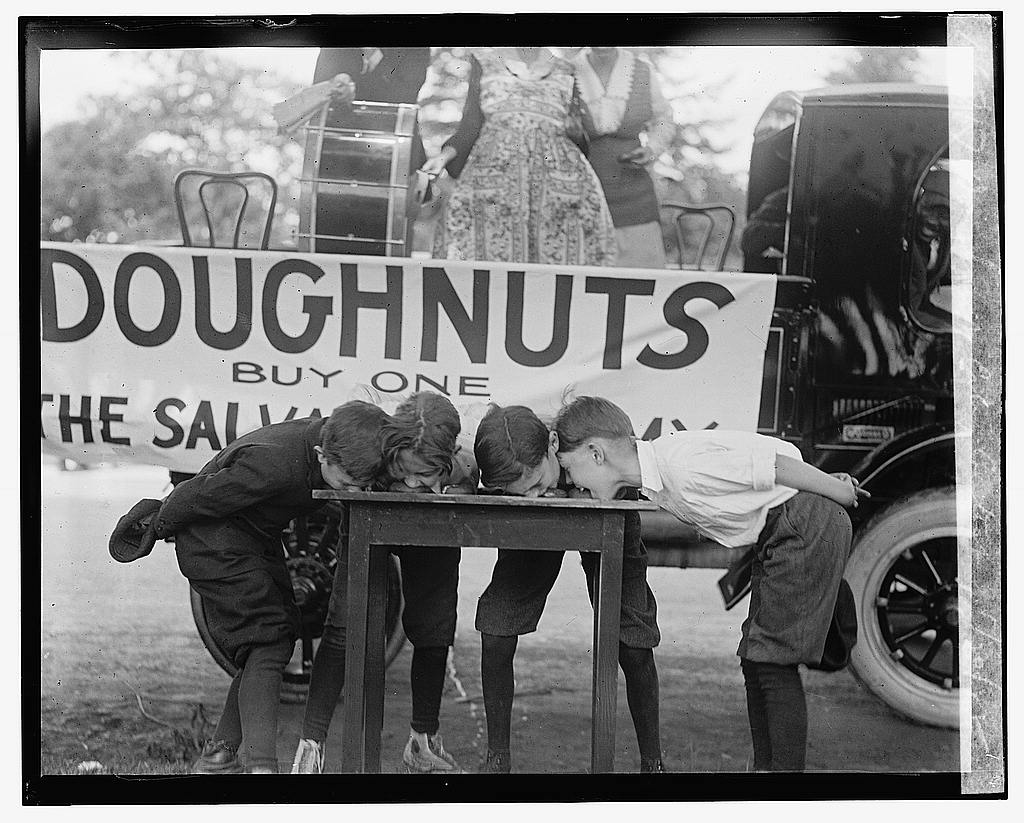

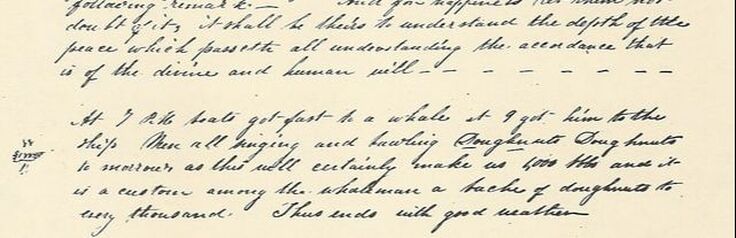

The cook would have then passed the dough on to the crew on deck, who took care of the cooking. The fritters were deep-fried in none other than whale oil in trypots - enormous, black cauldrons filled with shimmering whale oil rendered from whale blubber. The dough balls were lowered into these vats of oil, the crew watching them bob in the boiling gold before lifting them out with a skimmer. This long-handled strainer was designed to separate blubber from oil, but was perfectly suited for lifting doughnuts out as well. The crew would have wiped their dirty hands on the backsides of their pants and closed their eyes as they bit into these fresh, hot, puffy doughnuts, literally eating their bounty - a welcome change from the monotonous, paltry fare normally served on a whaleship. Several whaling wives who traveled with their husband-captains at sea recorded the serving of doughnuts. On Sunday, July 26, 1846, Mary Brewster wrote in her journal, “At 7PM boats got fast to a whale, at 9 got him to the ship. Men all singing and bawling [boiling] Doughnuts, Doughnuts tomorrow, as this will certainly make us 1000 bbls [barrels] and it is custom among the whaleman a bache [batch] of doughnuts to every thousand. Thus ends with good weather.” The next day, she noted, “This afternoon the men and frying doughnuts in the try pots and seem to be enjoying themselves merrily.” On another occasion, Henrietta Deblois stepped in to help with the cooking process. She recorded on the Merlin in 1858: “Today has been our doughnut fare, the first we have ever had. The Steward, Boy, and myself have been at work all the morning. We fried or boiled three tubs for the forecastle [sleeping area for crew] - one for the steerage. In the afternoon about one tub full for the cabin and right good were they too, not the least taste of oil – they came out of the pots perfectly dry. The skimmer was so large that they could take out a 1/2 of a peck at a time. I enjoyed it mightily." While whale oil was typically off-tasting, those who ate the donuts described only deliciousness. One exception was missionary Betsey Stockton, who sailed on a whaler to Hawaii in 1822. She wrote, “The crew [is] engaged in making oil of two black fish [whales] killed yesterday… we have had corn parched in the oil; and doughnuts fried in it. Some of the company liked it very much. I could not prevail on myself to eat it.” Keep an eye out for special offers from local donut shops in celebration of this day!

Read More:

|

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed