|

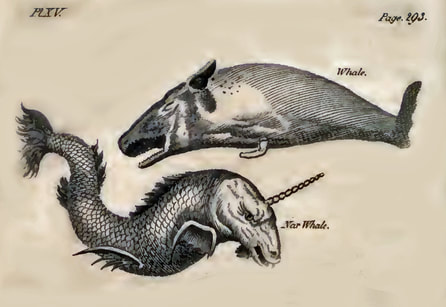

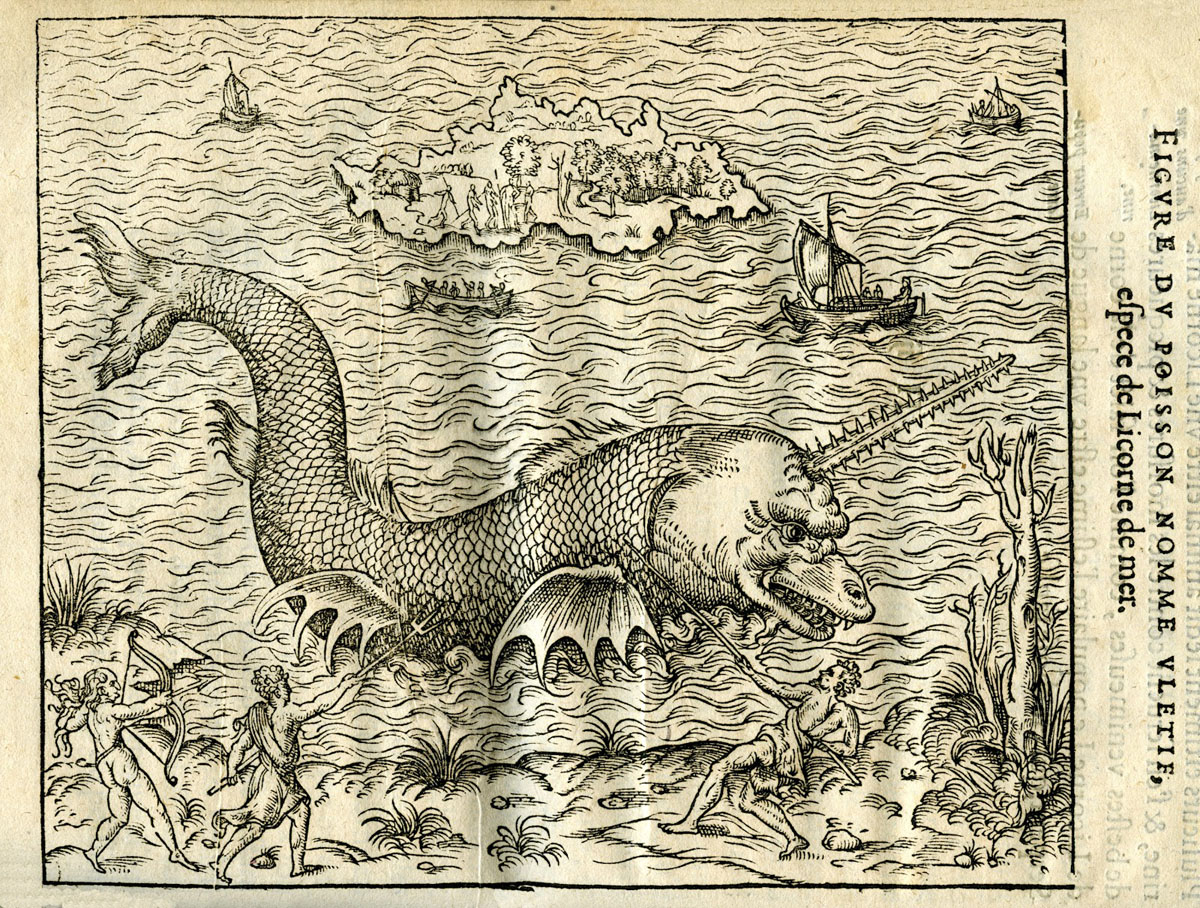

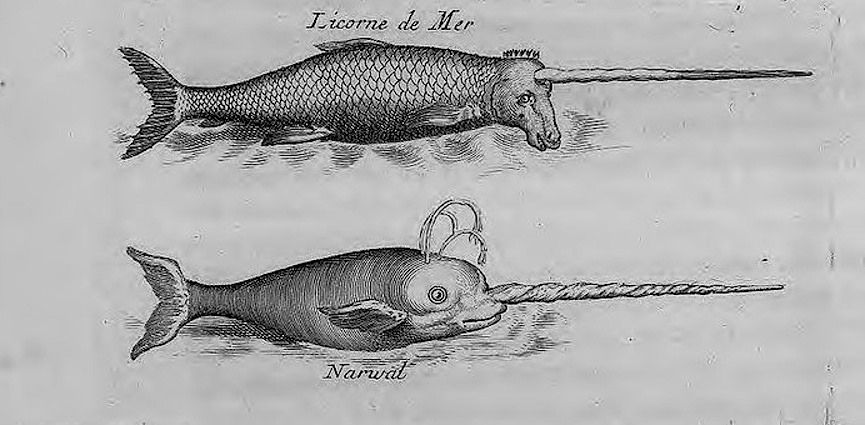

By Brenna McCormick-Thompson, Museum Educator  From Goldsmith's History of the Earth, 1807 From Goldsmith's History of the Earth, 1807 Every year, the Whaling Museum conducts outreach programs in schools and libraries across Long Island. Our educators pack up some of the museum’s most interesting artifacts and travel to share them with kids from Queens to Riverhead. Of the many items we bring - antique compasses, battle-worn harpoons, glittering deck prisms, and fear-inspiring megalodon teeth - few are as popular as a small, delicately spiraled segment of whalebone: the very tip of a narwhal tusk. This tusk is actually a tooth, which most male (and very rarely female) narwhals grow out of the front of their heads. The purpose of these elongated teeth is not definitively known, and is still hotly debated among the scientists who study these small arctic whales. Of all whales, the narwhal in particular has always been rather mysterious. Gathering information about these creatures, never mind even locating them, has always been a tricky business since they spend their lives hidden away in deep, dark arctic seas under thick layers of ice. It’s perhaps this aura of mystery that makes the narwhal the perfect alter ego of one of the most popular mythical creatures: the unicorn. Even for kids who recognize the tusk for what it is, the thrill of holding a “real” unicorn horn is palpable...and rather curious. How did the enlarged canine of an isolated species of arctic whale come to be so fundamentally associated with a magical horned horse? To uncover the origins of the unicorn myth, we have to travel back to Ancient Greece. In the 4th Century BCE, Greek physician Ctesias was travelling through Persia when he heard tales of an exotic land beyond the Indus River. Captivated by the accounts he heard of the strange beasts and curious peoples who inhabited the land we now call India, Ctesias took it upon himself to record these wonders for audiences back home. The resulting work, Indica, was an odd compilation of faithfully recorded descriptions of contemporary Indian beliefs and customs, and fanciful portraits of astonishing creatures. Among the latter is an account of the “wild asses in India the size of horses and even bigger.” Ctesias writes that these animals “have a horn in the middle of their brow one and a half cubits in length. The bottom part of the horn for as much as two palms towards the brow is bright white. The tip of the horn is sharp and crimson in color while the rest in the middle is black. They say that whoever drinks from the horn (which they fashion into cups) is immune to seizures and the holy sickness and suffers no effects from poison.” The creature described by Ctesias, which the Greeks came to know as monoceros (one-horned) and which later the Romans called unicornus, was most likely an Indian rhinoceros. Having no exposure to such an animal, and with only the words “asses” and “horses” to serve as a guide, subsequent ancient and medieval scholars struggled for centuries to describe this seemingly fantastical beast. Consequently, the unicorns depicted in early bestiaries are patchwork creatures - curious combinations of lions, goats, and deer - always vaguely equine in nature, but never the gleaming white horse we’ve come to know. The most striking difference between ancient and modern unicorns is the horn itself. Early unicorns were often given smooth, curved horns, surprisingly reminiscent of rhinoceros tusks. Though the creators of these images had undoubtedly never seen a rhinoceros in person, it’s possible that they may have come across the horn of one of these animals posing as a unicorn relic. This image of the unicorn seemed to change as narwhal tusks were gradually introduced into the European market. Appearing first in northern regions, these tusks were possibly distributed by the Viking sailors who were among the only people to venture into the arctic realms of these whales. These elegant, pale horns so captured the medieval imagination that the concept of the unicorn changed to better correspond to these strikingly beautiful artifacts. Unicorns transformed from beastly hybrid monsters to graceful beings who were so pure of spirit they could only be tamed by the fairest of maidens. Legends and artwork featuring the new, refined unicorn exploded across the continent, all but obliterating any memory of the fierce Indian beast from which the myth originally came. By the time Marco Polo embarked on his travels through Asia towards the end of the 13th Century, the notion of the gleaming, white unicorn was so absolute, that it was with great confusion and disappointment that he proclaimed “'Tis a passing ugly beast to look upon, and is not in the least like that which our stories tell of as being caught in the lap of a virgin; in fact, 'tis altogether different from what we fancied.” Little by little, Europeans recognized that their concept of the unicorn was inspired by two very real, very different creatures. Though both the rhinoceros and the narwhal have since left the realm of legend and progressed into the world of science, each animal retains echoes of their mythic pasts. The horn of the Indian rhinoceros (whose Latin name is appropriately Rhinoceros unicornis) is tragically still valued for its alleged medicinal properties. As for narwhal tusks, they seem to have retained the aura of mystery and magic that so deeply enthralled so many people centuries ago. Though it’s clear that these whales were not the original inspiration for the unicorn myth, we certainly have their stunning tusks to thank for transforming unicorns into the magnificent creatures we know today.  Brenna brings a wealth of maritime knowledge to the Whaling Museum. She wrote her dissertation on the Representations of Collective Memory and National Identity Aboard the Cutty Sark while at Georgetown University. With an MA in Global History and experience teaching at the Westchester Children’s Museum, she is especially adept at interpreting museum artifacts for education programs involving a wide array of age groups and learning styles.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

WhyFollow the Whaling Museum's ambition to stay current, and meaningful, and connected to contemporary interests. Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

AuthorWritten by staff, volunteers, and trustees of the Museum! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed